Related Research Articles

The Sutta Piṭaka is the second of the three divisions of the Tripiṭaka, the definitive canonical collection of scripture of Theravada Buddhism. The other two parts of the Tripiṭaka are the Vinaya Piṭaka and the Abhidhamma Piṭaka. The Sutta Pitaka contains more than 10,000 suttas (teachings) attributed to the Buddha or his close companions.

Śrāvaka (Sanskrit) or Sāvaka (Pali) means "hearer" or, more generally, "disciple". This term is used in Buddhism and Jainism. In Jainism, a śrāvaka is any lay Jain so the term śrāvaka has been used for the Jain community itself. Śrāvakācāras are the lay conduct outlined within the treaties by Śvetāmbara or Digambara mendicants. "In parallel to the prescriptive texts, Jain religious teachers have written a number of stories to illustrate vows in practice and produced a rich répertoire of characters.".

The Mahāparinibbāṇa Sutta is Sutta 16 in the Digha Nikaya, a scripture belonging to the Sutta Pitaka of Theravada Buddhism. It concerns the end of Gautama Buddha's life - his parinibbana - and is the longest sutta of the Pāli Canon. Because of its attention to detail, it has been resorted to as the principal source of reference in most standard accounts of the Buddha's death.

In Buddhism, an āgama is a collection of early Buddhist texts.

The Dīgha Nikāya is a Buddhist scriptures collection, the first of the five Nikāyas, or collections, in the Sutta Piṭaka, which is one of the "three baskets" that compose the Pali Tipiṭaka of Theravada Buddhism. Some of the most commonly referenced suttas from the Digha Nikaya include the Mahāparinibbāṇa Sutta, which describes the final days and passing of the Buddha, the Sigālovāda Sutta in which the Buddha discusses ethics and practices for lay followers, and the Samaññaphala Sutta and Brahmajāla Sutta which describe and compare the point of view of the Buddha and other ascetics in India about the universe and time ; and the Poṭṭhapāda Sutta, which describes the benefits and practice of Samatha meditation.

The Khuddaka Nikāya is the last of the five Nikāyas, or collections, in the Sutta Pitaka, which is one of the "three baskets" that compose the Pali Tipitaka, the sacred scriptures of Theravada Buddhism. This nikaya consists of fifteen (Thailand), fifteen, or eighteen books (Burma) in different editions on various topics attributed to the Lord Buddha and his chief disciples.

Upāsaka (masculine) or Upāsikā (feminine) are from the Sanskrit and Pāli words for "attendant". This is the title of followers of Buddhism who are not monks, nuns, or novice monastics in a Buddhist order, and who undertake certain vows. In modern times they have a connotation of dedicated piety that is best suggested by terms such as "lay devotee" or "devout lay follower".

The brahmavihārā are a series of four Buddhist virtues and the meditation practices made to cultivate them. They are also known as the four immeasurables or four infinite minds. The brahmavihārā are:

- loving-kindness or benevolence

- compassion

- empathetic joy

- equanimity

Pali literature is concerned mainly with Theravada Buddhism, of which Pali is the traditional language. The earliest and most important Pali literature constitutes the Pāli Canon, the authoritative scriptures of Theravada school.

Anussati means "recollection," "contemplation," "remembrance," "meditation", and "mindfulness". It refers to specific Buddhist meditational or devotional practices, such as recollecting the sublime qualities of the Buddha, which lead to mental tranquillity and abiding joy. In various contexts, the Pali literature and Sanskrit Mahayana sutras emphasise and identify different enumerations of recollections.

Buddhist ethics are traditionally based on what Buddhists view as the enlightened perspective of the Buddha. The term for ethics or morality used in Buddhism is Śīla or sīla (Pāli). Śīla in Buddhism is one of three sections of the Noble Eightfold Path, and is a code of conduct that embraces a commitment to harmony and self-restraint with the principal motivation being nonviolence, or freedom from causing harm. It has been variously described as virtue, moral discipline and precept.

Humans in Buddhism are the subjects of an extensive commentarial literature that examines the nature and qualities of a human life from the point of view of humans' ability to achieve enlightenment. In Buddhism, humans are just one type of sentient being, that is a being with a mindstream. In Sanskrit Manushya means an Animal with a mind. In Sanskrit the word Manusmriti associated with Manushya was used to describe knowledge through memory. The word Muun or Maan means mind. Mind is collection of past experience with an ability of memory or smriti. Mind is considered as an animal with a disease that departs a soul from its universal enlightened infinitesimal behavior to the finite miserable fearful behavior that fluctuates between the state of heaven and hell before it is extinguished back to its infinitesimal behavior.

The Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta is a Buddhist scripture that is considered by Buddhists to be a record of the first sermon given by Gautama Buddha, the Sermon in the Deer Park at Sarnath. The main topic of this sutta is the Four Noble Truths, which refer to and express the basic orientation of Buddhism in a formulaic expression. This sutta also refers to the Buddhist concepts of the Middle Way, impermanence, and dependent origination.

In English translations of Buddhist texts, householder denotes a variety of terms. Most broadly, it refers to any layperson, and most narrowly, to a wealthy and prestigious familial patriarch. In contemporary Buddhist communities, householder is often used synonymously with laity, or non-monastics.

The Upajjhatthana Sutta, also known as the Abhiṇhapaccavekkhitabbaṭhānasutta in the Chaṭṭha Saṅgāyana Tipiṭaka, is a Buddhist discourse famous for its inclusion of five remembrances, five facts regarding life's fragility and our true inheritance. The discourse advises that these facts are to be reflected upon often by all.

The Dighajanu Sutta, also known as the Byagghapajja Sutta or Vyagghapajja Sutta, is part of the Anguttara Nikaya. For Theravadin scholars, this discourse of the Pāli Canon is one of several considered key to understanding Buddhist lay ethics. In this discourse, the Buddha instructs a householder named Dīghajāṇu Vyagghapajja, a Koliyan householder, on eight personality traits or conditions that lead to happiness and well-being in this and future lives.

The sub-commentaries are primarily commentaries on the commentaries on the Pali Canon of Theravada Buddhism, written in Sri Lanka. This literature continues the commentaries' development of the traditional interpretation of the scriptures. These sub-commentaries were begun during the reign of Parākramabāhu I (1123–1186) under prominent Sri Lankan scholars such as Sāriputta Thera, Mahākassapa Thera of Dimbulagala Vihāra and Moggallāna Thera.

Buddhist views, although varying on a series of canons within the three branches of Buddhism, observe the concept of euthanasia, or "mercy killing", in a denunciatory manner. Such methods of euthanasia include voluntary, involuntary, and non-voluntary. In the past, as one school of Buddhism evolved into the next, their scriptures recorded through the oral messages of Buddha himself on Buddhist principles and values followed, guiding approximately 500 million Buddhists spanning the globe on their path to nirvana. In the Monastic Rule, or Vinaya, a consensus is reached by the Buddha on euthanasia and assisted suicide that expresses a lack of fondness of its practice. Buddhism does not confirm that life should be conserved by implementing whatever is necessary to postpone death, but instead expresses that the intentional precipitation of death is ethically inadmissible in every condition one is presented in.

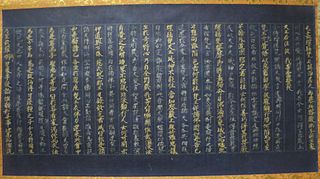

The Pāli Canon is the standard collection of scriptures in the Theravada Buddhist tradition, as preserved in the Pāli language. It is the most complete extant early Buddhist canon. It derives mainly from the Tamrashatiya school.

Jīvaka was the personal physician of the Buddha and the Indian King Bimbisāra. He lived in Rājagṛha, present-day Rajgir, in the 5th century BCE. Sometimes described as the "Medicine King", he figures prominently in legendary accounts in Asia as a model healer, and is honoured as such by traditional healers in several Asian countries.

References

- ↑ Dhammika, S. Vejjavatapada: The Buddhist Physician's Vow, Singapore, 2013, p.4

- ↑ Dhammapada ed. Hinuber. O. Von and Norman, K. R. Oxford, 1994

- ↑ Vinaya Piṭaka, Oldenberg, H. ed. 1879-83. London, Vol.I,p.302

- ↑ See Asceticism and Healing in Ancient India: Medicine in the Buddhist Monastery, Kenneth, G, Zysk, Delhi, 1998.

- ↑ Saṃyutta Nikāya, ed. L. Feer, PTS London 1884-98, Vol.IV,p.230

- ↑ Anguttara Nikāya, ed. Morris, R. and Hardy, E. editor (1885-1900). PTS London, Vol. III,p. 144; and Majjhima Nikāya, ed. V. Trenchner, R. Chalmers, PTS London 1887-1902, Vol. I, p.473

- ↑ Api ca gilānupaṭṭhākā bahūpakārā, Vinaya I, 303. This was in contrast to Brahmanism which looked upon doctors with disdain. See Buddhism in the Shadow of Brahmanism, Johannes Bronkhorst, 2011, pp.115-6.

- ↑ Zysk, p.43

- ↑ Anguttara Nikaya III, p.144

- ↑ Anguttara Nikaya I, p.121

- ↑ Dhammika, p.5

- ↑ Anguttara Nikāya III,297; Saṃyutta Nikāya V,381. Later Buddhist literature often encourages caring for and visiting the sick. The Brahmajala Sūtra says: "If a disciple of the Buddha sees anyone who is sick, he should provide for that person's needs as if he were making an offering to the Buddha." See Brahma Net Sutra, STCUSC, New York, 1998, VI,9. The Saddhammopāyana (Sri Lanka 12th century) says: "Nursing the sick was much praised by the Great Compassionate One and is it a wonder that he would do so? For the Sage sees the welfare of others as his own and thus that he should act as a benefactor is no surprise. This is why attending to the sick has been praised by the Buddha. One practicing great virtue should have loving concern for others." See Sadddhammopāyana, edited by Richard Morris, Journal of the Pali Text Society, 1887, pp.35-72.

- ↑ An English Translation of the Sushruta Samhita Based on Original Sanskrit Text, Bhishagratna, K. K. 1907, 3 vols.Varanasi, XXVII