Praxiteles of Athens, the son of Cephisodotus the Elder, was the most renowned of the Attica sculptors of the 4th century BC. He was the first to sculpt the nude female form in a life-size statue. While no indubitably attributable sculpture by Praxiteles is extant, numerous copies of his works have survived; several authors, including Pliny the Elder, wrote of his works; and coins engraved with silhouettes of his various famous statuary types from the period still exist.

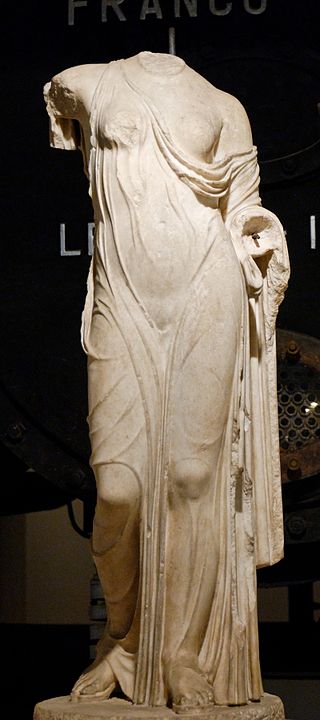

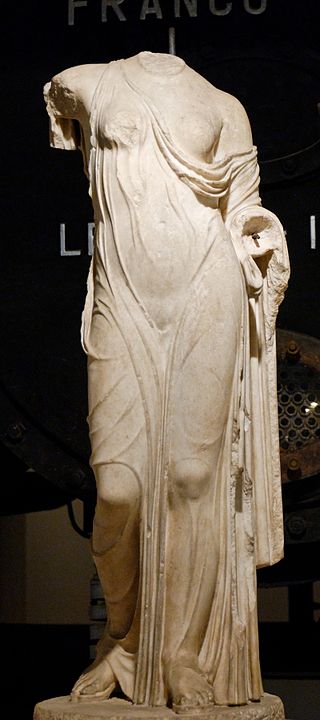

The Winged Victory of Samothrace, or the Niké of Samothrace, is a votive monument originally found on the island of Samothrace, north of the Aegean Sea. It is a masterpiece of Greek sculpture from the Hellenistic era, dating from the beginning of the 2nd century BC. It is composed of a statue representing the goddess Niké (Victory), whose head and arms are missing and its base is in the shape of a ship's bow.

The sculpture of ancient Greece is the main surviving type of fine ancient Greek art as, with the exception of painted ancient Greek pottery, almost no ancient Greek painting survives. Modern scholarship identifies three major stages in monumental sculpture in bronze and stone: the Archaic, Classical (480–323) and Hellenistic. At all periods there were great numbers of Greek terracotta figurines and small sculptures in metal and other materials.

The Aphrodite of Knidos was an Ancient Greek sculpture of the goddess Aphrodite created by Praxiteles of Athens around the 4th century BC. It was one of the first life-sized representations of the nude female form in Greek history, displaying an alternative idea to male heroic nudity. Praxiteles' Aphrodite was shown nude, reaching for a bath towel while covering her pubis, which, in turn leaves her breasts exposed. Up until this point, Greek sculpture had been dominated by male nude figures. The original Greek sculpture is no longer in existence; however, many Roman copies survive of this influential work of art. Variants of the Venus Pudica are the Venus de' Medici and the Capitoline Venus.

Alexandros of Antioch was a Greek sculptor of the Hellenistic age. He is thought to be the sculptor of the famous Venus de Milo statue.

Hellenistic art is the art of the Hellenistic period generally taken to begin with the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and end with the conquest of the Greek world by the Romans, a process well underway by 146 BC, when the Greek mainland was taken, and essentially ending in 30 BC with the conquest of Ptolemaic Egypt following the Battle of Actium. A number of the best-known works of Greek sculpture belong to this period, including Laocoön and His Sons, Venus de Milo, and the Winged Victory of Samothrace. It follows the period of Classical Greek art, while the succeeding Greco-Roman art was very largely a continuation of Hellenistic trends.

The Venus de' Medici or Medici Venus is a 1.53 m tall Hellenistic marble sculpture depicting the Greek goddess of love Aphrodite. It is a 1st-century BC marble copy, perhaps made in Athens, of a bronze original Greek sculpture, following the type of the Aphrodite of Knidos, which would have been made by a sculptor in the immediate Praxitelean tradition, perhaps at the end of the century. It has become one of the navigation points by which the progress of the Western classical tradition is traced, the references to it outline the changes of taste and the process of classical scholarship. It is housed in the Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy.

The Esquiline Venus, depicting the goddess Venus, is a smaller-than-life-size Roman nude marble sculpture of a female in sandals and a diadem headdress. It is widely viewed as a 1st-century AD Roman copy of a Greek original from the 1st century BC. It is also a possible depiction of the Ptolemaic ruler Cleopatra VII.

The Crouching Venus is a Hellenistic model of Venus surprised at her bath. Venus crouches with her right knee close to the ground, turns her head to the right and, in most versions, reaches her right arm over to her left shoulder to cover her breasts. To judge by the number of copies that have been excavated on Roman sites in Italy and France, this variant on Venus seems to have been popular.

The Ares Borghese is a Roman marble statue of the imperial era. It is 2.11 metres high. It is identifiable as Ares by the helmet and by the ankle ring given to him by his lover Aphrodite. This statue possibly preserves some features of an original work in bronze, now lost, of the 5th century BC.

The Venus Genetrix is a sculptural type which shows the Roman goddess Venus in her aspect of Genetrix, as she was honoured by the Julio-Claudian dynasty of Rome, which claimed her as their ancestor. Contemporary references identify the sculptor as a Greek named Arcesilaus. The statue was set up in Julius Caesar's new forum, probably as the cult statue in the cella of his temple of Venus Genetrix. Through this historical chance, a Roman designation is applied to an iconological type of Aphrodite that originated among the Greeks.

The Venus of Arles is a 1.94-metre-high (6.4 ft) sculpture of Venus at the Musée du Louvre. It is in Hymettus marble and dates to the end of the 1st century BC.

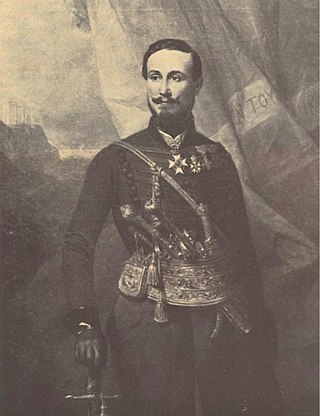

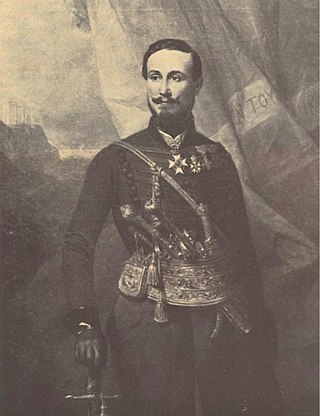

Olivier Voutier was a French naval officer who discovered the statue of the Venus de Milo in 1820, and fought in the Greek War of Independence.

Alain Pasquier is a French art historian specialising in ancient Greek art, museography and conservation.

The Venus Callipyge, also known as the Aphrodite Kallipygos or the Callipygian Venus, all literally meaning "Venus of the beautiful buttocks", is an Ancient Roman marble statue, thought to be a copy of an older Greek original. In an example of anasyrma, it depicts a partially draped woman, raising her light peplos to uncover her hips and buttocks, and looking back and down over her shoulder, perhaps to evaluate them. The subject is conventionally identified as Venus (Aphrodite), though it may equally be a portrait of a mortal woman.

Ancient Greek art stands out among that of other ancient cultures for its development of naturalistic but idealized depictions of the human body, in which largely nude male figures were generally the focus of innovation. The rate of stylistic development between about 750 and 300 BC was remarkable by ancient standards, and in surviving works is best seen in sculpture. There were important innovations in painting, which have to be essentially reconstructed due to the lack of original survivals of quality, other than the distinct field of painted pottery.

The Diana of Gabii is a statue of a woman in drapery which probably represents the goddess Artemis and is traditionally attributed to the sculptor Praxiteles. It became part of the Borghese collection and is now conserved in the Louvre with the inventory number Ma 529.

The Head of Arles, formerly known also as the Head of Livia or the Head with the broken nose is a fragment of a Roman marble statue in two parts, of which only the bust remains, which probably depicts Venus (Aphrodite) and was discovered in the ruins of the Ancient Theatre of Arles in 1823 during the removal of accreted material from the theatre. The Head of Arles represents an iconographic type called Aspremont-Lynden/Arles. It is now part of the permanent exhibition of the Musée de l'Arles et de la Provence antiques with the inventory number FAN.92.00.405.

Aphrodite of Rhodes also known as the Crouching Venus of Rhodes is a marble sculpture of the Greek goddess Aphrodite housed in the Archaeological Museum of Rhodes in Rhodes, Greece. It depicts Aphrodite in the crouching Venus pose, where the goddess crouches her right knee close to the ground and turns her head to the right. It is considered to be one of the most important hallmarks of Rhodes today.

Armed Aphrodite is a first-century AD Roman marble sculpture depicting Aphrodite Areia, or the war-like aspect of the Greek goddess Aphrodite, who was more commonly worshipped as a goddess of beauty and love. It is modelled after a lost Greek original of the fourth century BC made by Polykleitos the Younger, and is now kept in the National Archaeological Museum of Athens in Greece with accession number 262.

![Venus de Milo drawn by Auguste Debay. The inscribed plinth, if originally part of the Venus, identifies the sculptor as [---]andros of Antioch on the Maeander and supports a date for the work in the Hellenistic period. Paris Louvre Venus de Milo Debay drawing.jpg](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/0b/Paris_Louvre_Venus_de_Milo_Debay_drawing.jpg/220px-Paris_Louvre_Venus_de_Milo_Debay_drawing.jpg)