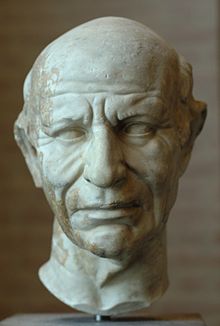

Verism was a realistic style in Roman art. It principally occurred in portraiture of politicians, whose imperfections of the face were exacerbated in order to highlight their old age and gravitas . The word comes from Latin verus (true).

Verism was a realistic style in Roman art. It principally occurred in portraiture of politicians, whose imperfections of the face were exacerbated in order to highlight their old age and gravitas . The word comes from Latin verus (true).

Verism first appeared as the artistic preference of the Roman people during the late Roman Republic (147–30 BC) and was often used for Republican portraits or for the head of “pseudo-athlete” sculptures. Verism, often described as "warts and all," shows the imperfections of the subject, such as warts, wrinkles, and furrows. It should be clearly noted that the term veristic in no way implies that these portraits are more "real." Rather, they too can be highly exaggerated or idealised, but within a different visual idiom, one which favours wrinkles, furrows, and signs of age as indicators of gravity and authority. Age during the Late Republic was very highly valued and was synonymous with power, since one of the only ways to hold power in Roman society was to be part of the Senate. [1] : 37

It is debated among scholars and art historians whether these veristic portraits were truly blunt records of actual features or exaggerated features designed to make a statement about a person's personality. [2] : 54 It is widely held in academia that in the ancient world physiognomy revealed the character of a person; thus, the personality characteristics seen in veristic busts could be taken to express certain virtues very much admired during the Republic. [2] : 54 However, scholars can never know for certain the accuracy of portrait renditions made long before their own era.

Verism first appeared during the Late Republic. The subjects of veristic portraiture were almost exclusively men, and these men were usually of advanced age, for generally it was elders who held power in the Republic. [2] : 53 However, women are also seen in veristic portraiture, though to a lesser extent, and they too were almost always depicted as elderly. [2] : 53 A key example of this is a marble head found at Palombara, Spain. Carved between 40 BC and 30 BC, during the decade of the civil war that followed Julius Caesar's assassination, the woman's face shows her advanced age. [2] : 54 The artist carved the woman with sunken cheeks and pouches under her eyes to illustrate her age, much like male veristic portraiture of the time. [2] : 54

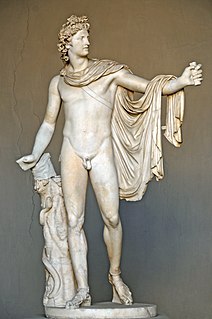

Verism, while the height of fashion during the Late Republican era, quickly fell into obscurity when Augustus and the rest of the Julio-Claudian dynasty (44 BC-68 AD) came to power. During this imperial reign, Greek Classical sculpture that featured "eternal youth" was favored over verism. It wasn't until after the suicide of Nero in 68 AD that verism was revived.

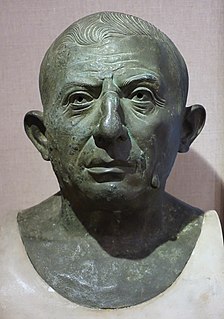

During the Year of the Four Emperors (68-69 AD) that resulted from Nero's suicide, when Galba, Vitellius, and Otho all grappled for the throne, verism made a resurgence, as seen in obverse portraits of Galba on bronze coins or marble busts of Vitellius. When Vespasian and his sons came to the throne the Flavian dynasty harnessed verism as a source of propaganda. Scholars believe that Vespasian used the shift from the Classical style to that of veristic portraiture to send a visual propagandistic message distinguishing him from the previous emperor. Vespasian's portraits showed him as an older, serious, and unpretentious man who was in every respect the anti-Nero: a career military officer concerned not for his own pleasure but for the welfare of the Roman people, the security of the Empire, and the solvency of the treasury. [2] : 123 Like the Romans from the Late Republic, Vespasian used veristic busts to underscore traditional values as a way to indicate to the Roman people a connection to the Republic. [2] : 123 With this reminder of the Late Republic, many Roman citizens were likely put at ease, knowing Vespasian was truly not like the previous emperor Nero, who represented everything the Republic abhorred. Yet after the Flavian period verism again faded into obscurity.

Veristic portraits of the late Republic hold a special fascination for classical art historians. Romans had inherited the use of sculpted marble heads from the Greeks but they did not inherit the veristic style from them. To scholars verism is uniquely Roman. Scholars have put forth multiple theories as to what or who were the precursors to Republican portraiture. Yet what is important to note is that there is not one single accepted theory of the origin of verism. The question of veristic style remains to this day essentially open and unresolved. Each theory, while plausible in its own way, will require further research and adequate consideration among scholars.

Scholars believe the ancient Italic peoples had an inclination to veristic representation leading to influence on later Roman art. [3] From a central Italian provenance in ancient times tribes from this area used Terracotta and Bronze to make a somewhat realistic portrayal of the human head. [1] : 30 Yet the ‘Italic’ heads, as they are called, are not seriously considered to be a favorable or strong theory held among scholars as being forerunners to the Republican portraits. [3] Scholars note that none of the realistic looking specimens can be shown to be earlier than the arrival of the new wave of Greek influence, rather than vice versa. [1] : 30

Scholars debate whether the heads of reclining figures on Etruscan cinerary urns are the forebears to Republican portraiture. [1] : 30 In Etruscan culture it was traditional and very common in Etruscan art to provide a naturalistic look to figures. Many cinerary urns are realistic looking or at least have harshly treated faces. [1] : 30 Scholars debate whether the realistic-looking style of head of these figures were a native creation which influenced the Romans, or whether the Romans influenced Etruria. [1] : 31 [4] The issues relating to chronological time casts doubts as to the accuracy of the theory.

Scholars consider the ancient Roman custom of making wax portraits, known as funerary or Death mask, of their ancestors as a convincing source for the veristic style. H. Drerup, a man of academia, argues that death masks molded straight from the face were early in use at Rome and exerted a ‘direct influence’ on Republican portraits. [1] : 31 Yet research has cast doubt on this theory. None of the funerary masks date before the 1st century AD. Evidence suggests the ancestral funerary masks merely kept pace with contemporary portraits in the round. [1] : 31 Chronology seems to be an issue with supporting the theory.

Scholars debate whether Egyptian influence started Roman verism. A group of portraits in hard Egyptian stone from the Roman Ptolemaic Kingdom show a harsh realism that is similarly seen in Republican portraits. [1] : 32 Scholars believe the Egyptian portraits began to be made before the Republican portraits and strongly influenced the Romans into establishing the veristic style when Egyptian priests and cults came into contact with Italy and Greece. [1] : 32 Although this theory like the others has merit, lack of concrete dating of this certain Egyptian style makes scholars doubt the creditability. Suggested stylistic dates often fluctuate by two or three centuries leaving scholars with no solid evidence for when the style of harshly realistic Egyptian portraiture begun. [1] : 31 Historians also note Romans did not have extensive military or commercial contact with Egypt before 30 BC, which was after the Late Republic when verism was being used on portraiture. [1] : 32 Scholars conclude that it is unlikely that Egyptian portraits influenced the Republican style.

Another theory presented to scholars in classical academia suggests that verism came about from Greek reactions to the conquering Romans. The theory goes that Romans in the Republic privately cherished the Hellenistic culture yet still held onto Republic values. [1] : 34 This interest leaked similar portrayals seen in the more realistic Hellenistic royal portraits of the Pontic and Bactrian kings of the first half of the 2nd century BC, such as the slight turn of their heads and upward glance of the eyes, into Roman veristic busts. [1] : 34 As Rome conquered Greece the empire saw an influx of talented Greek artists who were commissioned by the Romans to create their portraits that portrayed both the Hellenistic look and Republic values. Greek artists notoriously portrayed foreigners in an unfavorable light as a result of Greek attitudes of superiority. [1] : 35 For the Romans the Greeks found them not only to be foreigners, yet to be increasingly pompous and unlikeable oppressors. [1] : 35 Greek artists were little concerned to put the sitter's case favorably and portrayed Romans with an unsympathetic likeness. [1] : 35 As a result, the Greek artist would maintain the Hellenistic ‘pathos formula’ – turn of the head and neck, eyes looking upward – but the Greek sculptor, rather than adapt the Roman's features to a Hellenistic ruler ideal, had concentrated on bringing out an air of caricature to the face leading to what scholars call veristic portraiture. [1] : 36

Some scholars refute this theory as being the cause of verism. Scholars doubt that Romans would not have been angered by the caricature like portrayal given to them by the Greeks. Many question why the Romans did not punish the Greeks for this obvious slight. Yet scholars who are in favor of this theory state that the Romans simply didn't care for this over realistic portrayal. The Republic values of that time favored the straightforward and honest Roman citizen who did not need the deceits of art, but instead should be portrayed as they were, without artifice, for this would best bring out their Republican values. [1] : 37 As a result, some art historians, like R. R. R. Smith, believe verism originated from the negative Greek attitudes, if not somewhat unconscious attitudes, the artists felt towards these particular foreign clients, which was allowed to work itself into the Roman portraits because the artists had been freed from the usual obligation to flatter and idealized the sitter and instead allowed to sculpt without artifice. [1] : 38

Classical antiquity is the period of cultural history between the 8th century BC and the 6th century AD centred on the Mediterranean Sea, comprising the interlocking civilizations of ancient Greece and ancient Rome known as the Greco-Roman world. It is the period in which both Greek and Roman societies flourished and wielded huge influence throughout much of Europe, North Africa, and Western Asia.

The Hellenistic period of the Classical antiquity spans the period of Mediterranean history between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in 31 BC and the conquest of Ptolemaic Egypt the following year. The period of Greece prior to the Hellenistic era is known as Classical Greece, while the period afterwards is known as Roman Greece. The Ancient Greek word Hellas was originally the widely recognized name of Greece, from which the word Hellenistic was derived. "Hellenistic" is distinguished from "Hellenic" in that the first encompasses all territories under direct ancient Greek influence, while the latter refers to Greece itself. Instead, the term "Hellenistic" refers to that which is influenced by Greek culture, in this case, the East after the conquests of Alexander the Great.

The art of Ancient Rome, its Republic and later Empire includes architecture, painting, sculpture and mosaic work. Luxury objects in metal-work, gem engraving, ivory carvings, and glass are sometimes considered to be minor forms of Roman art, although they were not considered as such at the time. Sculpture was perhaps considered as the highest form of art by Romans, but figure painting was also highly regarded. A very large body of sculpture has survived from about the 1st century BC onward, though very little from before, but very little painting remains, and probably nothing that a contemporary would have considered to be of the highest quality.

Since ancient times, Greeks, Etruscans and Celts have inhabited the south, centre and north of the Italian peninsula respectively. The very numerous rock drawings in Valcamonica are as old as 8,000 BC, and there are rich remains of Etruscan art from thousands of tombs, as well as rich remains from the Greek colonies at Paestum, Agrigento and elsewhere. Ancient Rome finally emerged as the dominant Italian and European power. The Roman remains in Italy are of extraordinary richness, from the grand Imperial monuments of Rome itself to the survival of exceptionally preserved ordinary buildings in Pompeii and neighbouring sites. Following the fall of the Roman Empire, in the Middle Ages Italy, especially the north, remained an important centre, not only of the Carolingian art and Ottonian art of the Holy Roman Emperors, but for the Byzantine art of Ravenna and other sites.

The sculpture of ancient Greece is the main surviving type of fine ancient Greek art as, with the exception of painted ancient Greek pottery, almost no ancient Greek painting survives. Modern scholarship identifies three major stages in monumental sculpture in bronze and stone: the Archaic, Classical (480–323) and Hellenistic. At all periods there were great numbers of Greek terracotta figurines and small sculptures in metal and other materials.

Portrait painting is a genre in painting, where the intent is to represent a specific human subject. The term 'portrait painting' can also describe the actual painted portrait. Portraitists may create their work by commission, for public and private persons, or they may be inspired by admiration or affection for the subject. Portraits often serve as important state and family records, as well as remembrances.

Classical sculpture refers generally to sculpture from Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome, as well as the Hellenized and Romanized civilizations under their rule or influence, from about 500 BC to around 200 AD. It may also refer more precisely a period within Ancient Greek sculpture from around 500 BC to the onset of the Hellenistic style around 323 BC, in this case usually given a capital "C". The term "classical" is also widely used for a stylistic tendency in later sculpture, not restricted to works in a Neoclassical or classical style.

The study of Roman sculpture is complicated by its relation to Greek sculpture. Many examples of even the most famous Greek sculptures, such as the Apollo Belvedere and Barberini Faun, are known only from Roman Imperial or Hellenistic "copies". At one time, this imitation was taken by art historians as indicating a narrowness of the Roman artistic imagination, but, in the late 20th century, Roman art began to be reevaluated on its own terms: some impressions of the nature of Greek sculpture may in fact be based on Roman artistry.

Hellenistic art is the art of the Hellenistic period generally taken to begin with the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and end with the conquest of the Greek world by the Romans, a process well underway by 146 BCE, when the Greek mainland was taken, and essentially ending in 30 BCE with the conquest of Ptolemaic Egypt following the Battle of Actium. A number of the best-known works of Greek sculpture belong to this period, including Laocoön and His Sons, Venus de Milo, and the Winged Victory of Samothrace. It follows the period of Classical Greek art, while the succeeding Greco-Roman art was very largely a continuation of Hellenistic trends.

Augustus of Prima Porta is a full-length portrait statue of Augustus Caesar, the first emperor of the Roman Empire. The marble statue stands 2.08 metres tall and weighs 1,000 kilograms (2,200 lb). The statue was discovered on April 20, 1863, during archaeological excavations directed by Giuseppe Gagliardi at the Villa of Livia owned by Augustus' third and final wife, Livia Drusilla in Prima Porta. Livia had retired to the villa after Augustus's death in AD 14. The statue was first publicized by the German archeologist G. Henzen and was put into the Bulletino dell'Instituto di Corrispondenza Archaeologica. Carved by expert Greek sculptors, the statue is assumed to be a copy of a lost bronze original displayed in Rome. The Augustus of Prima Porta is now displayed in the Braccio Nuovo of the Vatican Museums. Since its discovery, it has become the best known of Augustus' portraits and one of the most famous sculptures of the ancient world.

The Ptolemaic Kingdom was an Ancient Greek state based in Egypt during the Hellenistic Period. It was founded in 305 BC by Ptolemy I Soter, a companion of Alexander the Great, and lasted until the death of Cleopatra VII in 30 BC. Ruling for nearly three centuries, the Ptolemies were the longest and most recent Egyptian dynasty of ancient origin.

Etruscan art was produced by the Etruscan civilization in central Italy between the 10th and 1st centuries BC. From around 750 BC it was heavily influenced by Greek art, which was imported by the Etruscans, but always retained distinct characteristics. Particularly strong in this tradition were figurative sculpture in terracotta, wall-painting and metalworking especially in bronze. Jewellery and engraved gems of high quality were produced.

Roman portraiture was one of the most significant periods in the development of portrait art. Originating from ancient Rome, it continued for almost five centuries. Roman portraiture is characterised by unusual realism and the desire to convey images of nature in the high quality style often seen in ancient Roman art. Some busts even seem to show clinical signs. Several images and statues made in marble and bronze have survived in small numbers. Roman funerary art includes many portraits such as married couple funerary reliefs, which were most often made for wealthy freedmen rather than the patrician elite.

In classical antiquity, the muscle cuirass, anatomical cuirass, or heroic cuirass is a type of cuirass made to fit the wearer's torso and designed to mimic an idealized male human physique. It first appears in late Archaic Greece and became widespread throughout the 5th and 4th centuries BC. Originally made from hammered bronze plate, boiled leather also came to be used. It is commonly depicted in Greek and Roman art, where it is worn by generals, emperors, and deities during periods when soldiers used other types.

The Meroë Head, or Head of Augustus from Meroë, is a larger-than-life-size bronze head depicting the first Roman emperor, Augustus, that was found in the ancient Nubian site of Meroë in modern Sudan in 1910. Long admired for its striking appearance and perfect proportions, it is now part of the British Museum's collection. It was looted from Roman Egypt in 24 BC by the forces of queen Amanirenas of Kush and brought back to Meroe, where it was buried beneath the staircase of a temple.

Ancient Greek art stands out among that of other ancient cultures for its development of naturalistic but idealized depictions of the human body, in which largely nude male figures were generally the focus of innovation. The rate of stylistic development between about 750 and 300 BC was remarkable by ancient standards, and in surviving works is best seen in sculpture. There were important innovations in painting, which have to be essentially reconstructed due to the lack of original survivals of quality, other than the distinct field of painted pottery.

The term Pseudo-athlete is used to describe works of art from the Late Republican period in Rome that combine a veristic head with an idealized body that references Classical Greek sculpture. Verism is a style of Roman portraiture that portrays an individual with aging facial features, most notably sagging skin around the mouth and eyes, short-cropped or balding hair, and deep wrinkles on the forehead and around the eyes and mouth. These features were emphasized under the tradition of verism in order to stress an advanced moral and psychological consciousness that comes along with advanced age. The veristic features of the pseudo-athlete's head are juxtaposed with the figure's body, which is depicted in the guise of an athletic youth from Classical Greece. The pseudo-athlete's body is typically depicted in heroic-nudity with highly smooth muscular forms and are often shown in an active stance or standing in an S-shaped curved known as contrapposto.

The Capitoline Brutus is an ancient Roman bronze bust commonly thought to depict the Roman consul Lucius Junius Brutus, usually dated to the late 4th to early 3rd centuries BC, but perhaps as late as the 2nd century BC, or early 1st century BC. The bust is 69 cm (27 in) in height and is currently located in the Hall of the Triumphs within the Capitoline Museums, Rome. Traditionally taken to be an early example of Roman portraiture and perhaps by an Etruscan artist influenced by Hellenistic art and contemporary Greek styles of portraiture, it may be "an archaizing work of the first century BC". The Roman head was provided with a toga-clad bronze bust during the Renaissance.

Roman Republican art is the artistic production that took place in Roman territory during the period of the Republic, conventionally from 509 BC to 27 BC.

Augustan and Julio-Claudian art is the artistic production that took place in the Roman Empire under the reign of Augustus and the Julio-Claudian dynasty, lasting from 44 BC to 69 AD. At that time Roman art developed towards a serene "neoclassicism", which reflected the political aims of Augustus and the Pax Romana, aimed at building a solid and idealized image of the empire.