Content of Vita Karoli Magni

The work begins with a preface that is mainly Einhard explaining why he is writing the book, highlighting the idea that he feels it is his duty and that he had such love for Charles that he felt that it would be a tragedy if he was forgotten. The book then moves onto the fall of the Merovingian family and how the Carolingian came to power, briefly describing the kingship of Pippin and the years of joint rule between Charlemagne and Carloman. [3]

A large section of the book is then dedicated to going through King Charles' many conquest and military campaigns. Einhard goes to great efforts to frame all of the conquests as justified and even righteous; in most cases, however, he is vague on the details of how the wars went and simply summaries the reasons for why they started and what the outcome was. [3]

Einhard then describes at length both Charlemagne physical appearance and his personality, making sure to highlight all the good qualities of Charles, especially his piety and moderation in all worldly pleasures. In this section of the book Einhard also takes time to talk about some of Charles' many children and seemingly tries to explain the reason that Charlemagne never let his daughters marry was because he simply loved them too much to be parted from them. [3] However it is Einhard's very brief description of the rebellion of Pippin the Hunchback that is of great importance as we know much more about Pippin than what Einhard says and many historians have seen it as blatant historical revisionism by Einhard. [4]

The final part of the book deals mainly with Charlemagne being crowned Roman Emperor on Christmas day of the year 800 and it also lays out his death and will as well as the ascension of his son Louis the Pious. The book clams that Charles had no idea that he was to be crowned emperor going so far as to state that:

"He at first had such an aversion that he declared that he would not have set foot in the Church the day that they [the imperial titles] were conferred, although it was a great feast-day, if he could have foreseen the design of the Pope". [3]

There has been a great debate among historians as to whether this view put forward by Einhard is correct, with most modern historians having reached the conclusion that Charlemagne must have definitely known about the Pope's plans long before it happened. The work ends with a copy of Charlemagne's will and a description of his burial bringing the book to a close on a rather somber note. [3]

Angilbert, Count of Ponthieu was a noble Frankish poet who was educated under Alcuin and served Charlemagne as a secretary, diplomat, and son-in-law. He is venerated as a pre-Congregation saint and is still honored on the day of his death, 18 February.

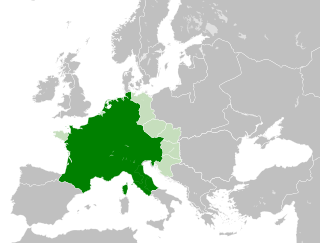

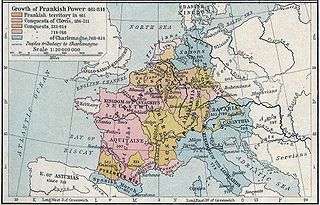

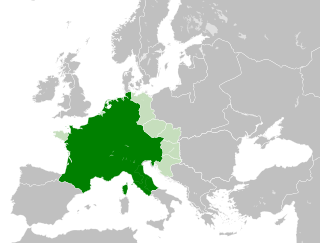

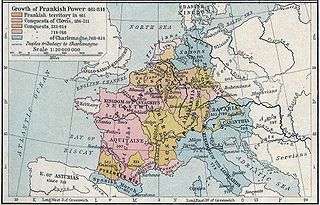

Charlemagne was King of the Franks from 768, King of the Lombards from 774, and Emperor of what is now known as the Carolingian Empire from 800, holding all these titles until his death in 814. Charlemagne succeeded in uniting the majority of Western and Central Europe, and was the first recognized emperor to rule in the west after the fall of the Western Roman Empire approximately three centuries earlier. Charlemagne's rule saw a program of political and social changes that had a lasting impact on Europe in the Middle Ages.

Einhard was a Frankish scholar and courtier. Einhard was a dedicated servant of Charlemagne and his son Louis the Pious; his main work is a biography of Charlemagne, the Vita Karoli Magni, "one of the most precious literary bequests of the early Middle Ages".

The Carolingian Empire (800–887) was a Frankish-dominated empire in Western and Central Europe during the Early Middle Ages. It was ruled by the Carolingian dynasty, which had ruled as kings of the Franks since 751 and as kings of the Lombards in Italy from 774. In 800, the Frankish king Charlemagne was crowned emperor in Rome by Pope Leo III in an effort to transfer the Roman Empire from the Byzantine Empire to Western Europe. The Carolingian Empire is sometimes considered the first phase in the history of the Holy Roman Empire.

The Carolingian dynasty was a Frankish noble family named after Charles Martel and his grandson Charlemagne, descendants of the Arnulfing and Pippinid clans of the 7th century AD. The dynasty consolidated its power in the 8th century, eventually making the offices of mayor of the palace and dux et princeps Francorum hereditary, and becoming the de facto rulers of the Franks as the real powers behind the Merovingian throne. In 751 the Merovingian dynasty which had ruled the Franks was overthrown with the consent of the Papacy and the aristocracy, and Pepin the Short, son of Martel, was crowned King of the Franks. The Carolingian dynasty reached its peak in 800 with the crowning of Charlemagne as the first Emperor of the Romans in the West in over three centuries. Nearly every monarch of France from Charlemagne's son Louis the Pious till the penultimate monarch of France Louis Philippe have been his descendants. His death in 814 began an extended period of fragmentation of the Carolingian Empire and decline that would eventually lead to the evolution of the Kingdom of France and the Holy Roman Empire.

Childeric III was King of the Franks from 743 until he was deposed in 751 by Pepin the Short. He was the last Frankish king from the Merovingian dynasty. Once Childeric was deposed, Pepin became king, initiating the Carolingian dynasty.

Abul-Abbas was an Asian elephant brought back to the Carolingian emperor Charlemagne by his diplomat Isaac the Jew. The gift was from the Abbasid caliph Harun al-Rashid and symbolizes the beginning of Abbasid–Carolingian relations. The elephant's name and events from his life are recorded in the Carolingian Annales regni Francorum, and he is mentioned in Einhard's Vita Karoli Magni. However, no references to the gift or to interactions with Charlemagne have been found in Abbasid records.

Himiltrude was the mother of Charlemagne's first-born son Pippin the Hunchback. Some historians have acknowledged her as the wife of Charlemagne, however, she is often referred to as a concubine.

Fastrada was queen consort of East Francia by marriage to Charlemagne, as his third wife.

Notker the Stammerer, Notker Balbulus, or simply Notker, was a Benedictine monk at the Abbey of Saint Gall active as a composer, poet and scholar. Described as "a significant figure in the Western Church", Notker made substantial contributions to both the music and literature of his time. He is usually credited with two major works of the Carolingian period: the Liber Hymnorum, which includes an important collection of early musical sequences, and an early biography of Charlemagne, the Gesta Karoli Magni. His other works include a biography of Saint Gall known as the Vita Sancti Galli and a martyrology, among others.

The Royal Frankish Annals, also called the Annales Laurissenses maiores, are a series of annals composed in Latin in the Carolingian Francia, recording year-by-year the state of the monarchy from 741 to 829. Their authorship is unknown, though Wilhelm von Giesebrecht suggested that Arno of Salzburg was the author of an early section surviving in the copy at Lorsch Abbey. The Annals are believed to have been composed in successive sections by different authors, and then compiled.

Lupo II is the third-attested historical duke of Gascony, appearing in history for the first time in 769. His ancestry is subject to scholarly debate.

Vita Hludovici or Vita Hludovici Imperatoris is an anonymous biography of Louis the Pious, Holy Roman Emperor and King of the Franks from AD 814 to 840.

Thegan of Trier was a Frankish Roman Catholic prelate and the author of Gesta Hludowici imperatoris which is a principal source for the life of the Holy Roman Emperor Louis the Pious, the son and successor of Charlemagne.

Saint Clement of Ireland (Clemens Scotus) (c. 750 – 818) is venerated as a saint by the Catholic Church.

Pepin, or Pippin the Hunchback was a Frankish prince. He was the eldest son of Charlemagne and noblewoman Himiltrude. He developed a humped back after birth, leading early medieval historians to give him the epithet "hunchback". He lived with his father's court after Charlemagne dismissed his mother and took another wife, Hildegard. Around 781, Pepin's half brother Carloman was rechristened as "Pepin of Italy"—a step that may have signaled Charlemagne's decision to disinherit the elder Pepin, for a variety of possible reasons. In 792, Pepin the Hunchback revolted against his father with a group of leading Frankish nobles, but the plot was discovered and put down before the conspiracy could put it into action. Charlemagne commuted Pepin's death sentence, having him tonsured and exiled to the monastery of Prüm instead. Since his death in 811, Pepin has been the subject of numerous works of historical fiction.

The Latin poem conventionally titled Visio Karoli Magni, and in the manuscripts Visio Domini Karoli Regis Francorvm, was written by an anonymous East Frank around 865. Sometimes classified as visionary literature, the Visio is not a typical example the genre, since the "vision" it presents is merely a dream.

The anonymous Saxon poet known as Poeta Saxo, who composed the medieval Latin Annales de gestis Caroli magni imperatoris libri quinque was probably a monk of Saint Gall or possibly Corvey. His Annales is one of the earliest poetic treatments of annalistic material and one of the earliest historical works to concentrate on Saxony. It is considered characteristic of the dénouement of the Carolingian Renaissance.

The siege of Trsat was a battle fought over possession of the town of Trsat in Liburnia, near the Croatian–Frankish border. The battle was fought in the autumn of 799 between the defending forces of Dalmatian Croatia under the leadership of Croatian duke Višeslav, and the invading Frankish army of the Carolingian Empire led by Eric of Friuli. The battle was a Croatian victory, and the Frankish commander Eric was killed during the siege.

Gersuinda was a concubine of the emperor Charlemagne, with whom he was in a relationship after the death of his last legitimate wife, Luitgard. According to Charlemagne's contemporary biographer, Einhard, Gersuinda was a Saxon, a people whom Charlemagne subdued over a thirty year period.