A transient ischemic attack (TIA), commonly known as a mini-stroke, is a minor stroke whose noticeable symptoms usually end in less than an hour. TIA causes the same symptoms associated with strokes, such as weakness or numbness on one side of the body, sudden dimming or loss of vision, difficulty speaking or understanding language, slurred speech, or confusion.

Dementia is the general name for a decline in cognitive abilities that impacts a person's ability to perform everyday activities. This typically involves problems with memory, thinking, and behavior. Aside from memory impairment and a disruption in thought patterns, the most common symptoms include emotional problems, difficulties with language, and decreased motivation. The symptoms may be described as occurring in a continuum over several stages. Dementia ultimately has a significant effect on the individual, caregivers, and on social relationships in general. A diagnosis of dementia requires the observation of a change from a person's usual mental functioning and a greater cognitive decline than what is caused by normal aging.

Vascular dementia (VaD) is dementia caused by problems in the blood supply to the brain, resulting from a cerebrovascular disease. Restricted blood supply (ischemia) leads to cell and tissue death in the affected region, known as an infarct. The three types of vascular dementia are subcortical vascular dementia, multi-infarct dementia, and stroke related dementia. Subcortical vascular dementia is brought about by damage to the small blood vessels in the brain. Multi-infarct dementia is brought about by a series of mini-strokes where many regions have been affected. The third type is stroke related where more serious damage may result. Such damage leads to varying levels of cognitive decline. When caused by mini-strokes, the decline in cognition is gradual. When due to a stroke, the cognitive decline can be traced back to the event.

Binswanger's disease, also known as subcortical leukoencephalopathy and subcortical arteriosclerotic encephalopathy, is a form of small-vessel vascular dementia caused by damage to the white brain matter. White matter atrophy can be caused by many circumstances including chronic hypertension as well as old age. This disease is characterized by loss of memory and intellectual function and by changes in mood. These changes encompass what are known as executive functions of the brain. It usually presents between 54 and 66 years of age, and the first symptoms are usually mental deterioration or stroke.

Cerebrovascular disease includes a variety of medical conditions that affect the blood vessels of the brain and the cerebral circulation. Arteries supplying oxygen and nutrients to the brain are often damaged or deformed in these disorders. The most common presentation of cerebrovascular disease is an ischemic stroke or mini-stroke and sometimes a hemorrhagic stroke. Hypertension is the most important contributing risk factor for stroke and cerebrovascular diseases as it can change the structure of blood vessels and result in atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis narrows blood vessels in the brain, resulting in decreased cerebral perfusion. Other risk factors that contribute to stroke include smoking and diabetes. Narrowed cerebral arteries can lead to ischemic stroke, but continually elevated blood pressure can also cause tearing of vessels, leading to a hemorrhagic stroke.

Stroke is a medical condition in which poor blood flow to the brain causes cell death. There are two main types of stroke: ischemic, due to lack of blood flow, and hemorrhagic, due to bleeding. Both cause parts of the brain to stop functioning properly.

Memory disorders are the result of damage to neuroanatomical structures that hinders the storage, retention and recollection of memories. Memory disorders can be progressive, including Alzheimer's disease, or they can be immediate including disorders resulting from head injury.

The prevention of dementia involves reducing the number of risk factors for the development of dementia, and is a global health priority needing a global response. Initiatives include the establishment of the International Research Network on Dementia Prevention (IRNDP) which aims to link researchers in this field globally, and the establishment of the Global Dementia Observatory a web-based data knowledge and exchange platform, which will collate and disseminate key dementia data from members states. Although there is no cure for dementia, it is well established that modifiable risk factors influence both the likelihood of developing dementia and the age at which it is developed. Dementia can be prevented by reducing the risk factors for vascular disease such as diabetes, high blood pressure, obesity, smoking, physical inactivity and depression. A study concluded that more than a third of dementia cases are theoretically preventable. Among older adults both an unfavorable lifestyle and high genetic risk are independently associated with higher dementia risk. A favorable lifestyle is associated with a lower dementia risk, regardless of genetic risk. In 2020, a study identified 12 modifiable lifestyle factors, and the early treatment of acquired hearing loss was estimated as the most significant of these factors, potentially preventing up to 9% of dementia cases.

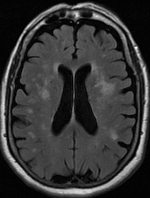

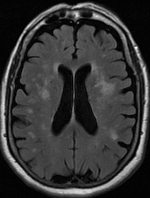

Leukoaraiosis is a particular abnormal change in appearance of white matter near the lateral ventricles. It is often seen in aged individuals, but sometimes in young adults. On MRI, leukoaraiosis changes appear as white matter hyperintensities (WMHs) in T2 FLAIR images. On CT scans, leukoaraiosis appears as hypodense periventricular white-matter lesions.

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disease that usually starts slowly and progressively worsens, and is the cause of 60–70% of cases of dementia. The most common early symptom is difficulty in remembering recent events. As the disease advances, symptoms can include problems with language, disorientation, mood swings, loss of motivation, self-neglect, and behavioral issues. As a person's condition declines, they often withdraw from family and society. Gradually, bodily functions are lost, ultimately leading to death. Although the speed of progression can vary, the typical life expectancy following diagnosis is three to nine years.

Complications of hypertension are clinical outcomes that result from persistent elevation of blood pressure. Hypertension is a risk factor for all clinical manifestations of atherosclerosis since it is a risk factor for atherosclerosis itself. It is an independent predisposing factor for heart failure, coronary artery disease, stroke, kidney disease, and peripheral arterial disease. It is the most important risk factor for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, in industrialized countries.

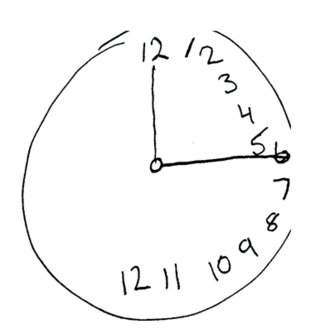

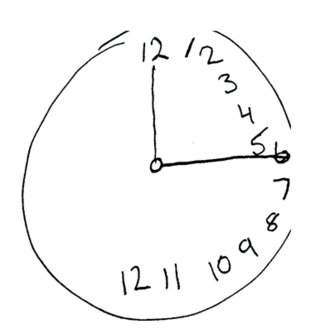

The Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) is a widely used screening assessment for detecting cognitive impairment. It was created in 1996 by Ziad Nasreddine in Montreal, Quebec. It was validated in the setting of mild cognitive impairment (MCI), and has subsequently been adopted in numerous other clinical settings. This test consists of 30 points and takes 10 minutes for the individual to complete. The original English version is performed in seven steps, which may change in some countries dependent on education and culture. The basics of this test include short-term memory, executive function, attention, focus, and more.

John David Spence is a Canadian medical doctor, medical researcher and Professor Emeritus at the University of Western Ontario. He is affiliated with the University of Western Ontario and the Robarts Research Institute, one of Canada's leading medical research organizations. Before his retirement from clinical practice in July 2022, he was also affiliated with the London Health Sciences Centre's University Hospital. He is a recognized expert in stroke prevention and stroke prevention research, with more than 600 peer-reviewed publications since 1970. He delivered more than 600 lectures on stroke prevention in 42 countries. In 2015, he received the Research Excellence Award from the Canadian Society for Atherosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology. In 2019, he was appointed a Member of the Order of Canada, and in 2020 he received the William Feinberg Award from the American Heart Association for excellence in clinical stroke research.

A silent stroke is a stroke that does not have any outward symptoms associated with stroke, and the patient is typically unaware they have suffered a stroke. Despite not causing identifiable symptoms, a silent stroke still causes damage to the brain and places the patient at increased risk for both transient ischemic attack and major stroke in the future. In a broad study in 1998, more than 11 million people were estimated to have experienced a stroke in the United States. Approximately 770,000 of these strokes were symptomatic and 11 million were first-ever silent MRI infarcts or hemorrhages. Silent strokes typically cause lesions which are detected via the use of neuroimaging such as MRI. The risk of silent stroke increases with age but may also affect younger adults. Women appear to be at increased risk for silent stroke, with hypertension and current cigarette smoking being amongst the predisposing factors.

Arno Villringer is a Director at the Department of Neurology at the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences in Leipzig, Germany; Director of the Department of Cognitive Neurology at University of Leipzig Medical Center; and Academic Director of the Berlin School of Mind and Brain and the Mind&Brain Institute, Berlin. He holds a full professorship at University of Leipzig and an honorary professorship at Charité, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin. From July 2022 to June 2025 he is the Chairperson of the Human Sciences Section of the Max Planck Society.

Cerebrolysin is a mixture of enzymatically treated peptides derived from pig brain whose constituents can include brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF), nerve growth factor (NGF), and ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF).

Joel Salinas is an American-born Nicaraguan neurologist, writer, and researcher, who is currently an assistant professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School. He practices general neurology, with subspecialty in behavioral neurology and neuropsychiatry, at the Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts. He is also a clinician-scientist at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and the Framingham Study at the Boston University School of Medicine.

Rebecca Gottesman is Senior Investigator and Stroke Branch Chief at the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) at the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Before joining NINDS, she was Professor of Neurology and Epidemiology at Johns Hopkins University. Gottesman completed a B.A. in Psychology at Columbia University (1995), an M.D. at Columbia University (2000), and a Ph.D. in Clinical Investigation at Johns Hopkins University (2007). She is a Fellow of the American Neurological Association (2012) and a Fellow of the American Heart Association (2015).

Miia K. Kivipelto is a Finnish neuroscientist and professor at the University of Eastern Finland and Karolinska Institute in Stockholm. Her research focuses on dementia and Alzheimer's disease.

Hypertension is a condition characterized by an elevated blood pressure in which the long term consequences include cardiovascular disease, kidney disease, adrenal gland tumors, vision impairment, memory loss, metabolic syndrome, stroke and dementia. It affects nearly 1 in 2 Americans and remains as a contributing cause of death in the United States. There are many genetic and environmental factors involved with the development of hypertension including genetics, diet, and stress.