Related Research Articles

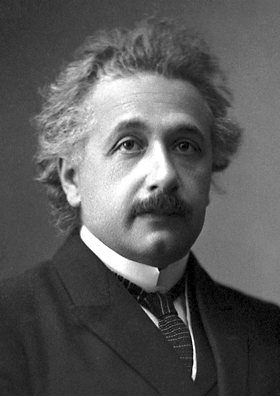

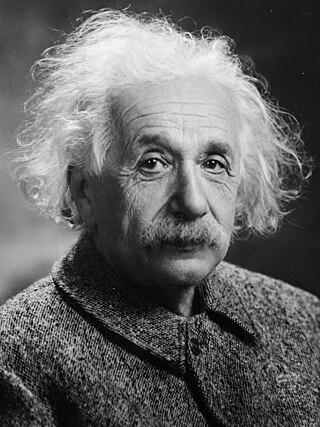

Albert Einstein was a German-born theoretical physicist who is widely held to be one of the greatest and most influential scientists of all time. Best known for developing the theory of relativity, Einstein also made important contributions to quantum mechanics, and was thus a central figure in the revolutionary reshaping of the scientific understanding of nature that modern physics accomplished in the first decades of the twentieth century. His mass–energy equivalence formula E = mc2, which arises from relativity theory, has been called "the world's most famous equation". He received the 1921 Nobel Prize in Physics "for his services to theoretical physics, and especially for his discovery of the law of the photoelectric effect", a pivotal step in the development of quantum theory. His work is also known for its influence on the philosophy of science.

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell, was a British mathematician, logician, philosopher, and public intellectual. He had influence on mathematics, logic, set theory, and various areas of analytic philosophy.

Martin Heidegger was a German philosopher who is best known for contributions to phenomenology, hermeneutics, and existentialism. He is often considered to be among the most important and influential philosophers of the 20th century.

Nothing, no-thing, or no thing, is the complete absence of anything as the opposite of something and an antithesis of everything. The concept of nothing has been a matter of philosophical debate since at least the 5th century BC. Early Greek philosophers argued that it was impossible for nothing to exist. The atomists allowed nothing but only in the spaces between the invisibly small atoms. For them, all space was filled with atoms. Aristotle took the view that there exists matter and there exists space, a receptacle into which matter objects can be placed. This became the paradigm for classical scientists of the modern age like Newton. Nevertheless, some philosophers, like Descartes, continued to argue against the existence of empty space until the scientific discovery of a physical vacuum.

Wilhelm Reich was an Austrian doctor of medicine and a psychoanalyst, a member of the second generation of analysts after Sigmund Freud. The author of several influential books, The Impulsive Character (1925), The Function of the Orgasm (1927), Character Analysis (1933), and The Mass Psychology of Fascism (1933), he became one of the most radical figures in the history of psychiatry.

Sir Joseph Rotblat was a Polish and British physicist. During World War II he worked on Tube Alloys and the Manhattan Project, but left the Los Alamos Laboratory on grounds of conscience after it became clear to him in 1944 that Germany had ceased development of an atomic bomb.

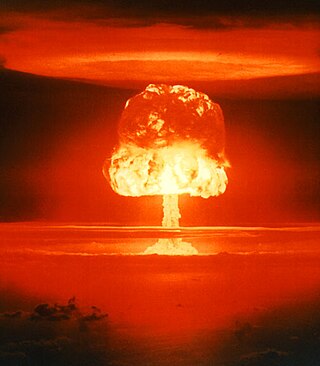

The Emergency Committee of Atomic Scientists (ECAS) was founded by Albert Einstein and Leó Szilárd in May, 1946, primarily as a fundraising and policy-making agency. Its aims were to warn the public of the dangers associated with the development of nuclear weapons, promote the peaceful use of nuclear energy, and ultimately work towards world peace, which was seen as the only way that nuclear weapons would not be used again.

The Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs is an international organization that brings together scholars and public figures to work toward reducing the danger of armed conflict and to seek solutions to global security threats. It was founded in 1957 by Joseph Rotblat and Bertrand Russell in Pugwash, Nova Scotia, Canada, following the release of the Russell–Einstein Manifesto in 1955.

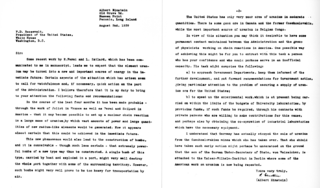

The Russell–Einstein Manifesto was issued in London on 9 July 1955 by Bertrand Russell in the midst of the Cold War. It highlighted the dangers posed by nuclear weapons and called for world leaders to seek peaceful resolutions to international conflict. The signatories included eleven pre-eminent intellectuals and scientists, including Albert Einstein, who signed it shortly before his death on 18 April 1955. Shortly after the release, philanthropist Cyrus S. Eaton offered to sponsor a conference—called for in the manifesto—in Pugwash, Nova Scotia, Eaton's birthplace. The conference, held in July 1957, became the first of the Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs.

The Baruch Plan was a proposal put forward by the United States government on 14 June 1946 to the United Nations Atomic Energy Commission (UNAEC) during its first meeting. Bernard Baruch wrote the bulk of the proposal, based on the March 1946 Acheson–Lilienthal Report. The Soviet Union, fearing the plan would preserve the American nuclear monopoly, declined in December 1946 in the United Nations Security Council to endorse Baruch's version of the proposal, and the Cold War phase of the nuclear arms race followed.

Edward Uhler Condon was an American nuclear physicist, a pioneer in quantum mechanics, and a participant during World War II in the development of radar and, very briefly, of nuclear weapons as part of the Manhattan Project. The Franck–Condon principle and the Slater–Condon rules are co-named after him.

A History of Western Philosophy is a 1946 book by British philosopher Bertrand Russell (1872–1970). A survey of Western philosophy from the pre-Socratic philosophers to the early 20th century, each major division of the book is prefaced by an account of the historical background necessary to understand the currents of thought it describes. When Russell was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1950, A History of Western Philosophy was cited as one of the books that won him the award. Its success provided Russell with financial security for the last part of his life. The book was criticised, however, for over-generalizations and omissions, particularly from the post-Cartesian period, but nevertheless became a popular and commercial success, and has remained in print from its first publication.

The Einstein–Szilard letter was a letter written by Leo Szilard and signed by Albert Einstein on August 2, 1939, that was sent to President of the United States Franklin D. Roosevelt. Written by Szilard in consultation with fellow Hungarian physicists Edward Teller and Eugene Wigner, the letter warned that Germany might develop atomic bombs and suggested that the United States should start its own nuclear program. It prompted action by Roosevelt, which eventually resulted in the Manhattan Project, the development of the first atomic bombs, and the use of these bombs on the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Philosopher Martin Heidegger joined the Nazi Party (NSDAP) on May 1, 1933, ten days after being elected Rector of the University of Freiburg. A year later, in April 1934, he resigned the Rectorship and stopped taking part in Nazi Party meetings, but remained a member of the Nazi Party until its dismantling at the end of World War II. The denazification hearings immediately after World War II led to Heidegger's dismissal from Freiburg, banning him from teaching. In 1949, after several years of investigation, the French military finally classified Heidegger as a Mitläufer or "fellow traveller." The teaching ban was lifted in 1951, and Heidegger was granted emeritus status in 1953, but he was never allowed to resume his philosophy chairmanship.

Aspects of philosopher, mathematician and social activist Bertrand Russell's views on society changed over nearly 80 years of prolific writing, beginning with his early work in 1896, until his death in February 1970.

Albert Einstein's religious views have been widely studied and often misunderstood. Albert Einstein stated "I believe in Spinoza's God". He did not believe in a personal God who concerns himself with fates and actions of human beings, a view which he described as naïve. He clarified, however, that, "I am not an atheist", preferring to call himself an agnostic, or a "religious nonbeliever." In other interviews, he stated that he thought that there is a "lawgiver" who sets the laws of the universe. Einstein also stated he did not believe in life after death, adding "one life is enough for me." He was closely involved in his lifetime with several humanist groups. Einstein rejected a conflict between science and religion, and held that cosmic religion was necessary for science.

Albert Einstein (1879–1955), a German-born scientist, was predominantly known during his lifetime for his development of the theory of relativity, his contributions to quantum mechanics, and many other notable achievements in modern physics. However, his political views also garnered much public interest due to his fame and involvement in political, humanitarian, and academic projects around the world.

Ernst Simmel was a German-American neurologist and psychoanalyst.

An anti-war movement is a social movement, usually in opposition to a particular nation's decision to start or carry on an armed conflict. The term anti-war can also refer to pacifism, which is the opposition to all use of military force during conflicts, or to anti-war books, paintings, and other works of art. Some activists distinguish between anti-war movements and peace movements. Anti-war activists work through protest and other grassroots means to attempt to pressure a government to put an end to a particular war or conflict or to prevent it in advance.

World federalism or global federalism is a political ideology advocating a democratic, federal world government. A world federation would have authority on issues of global reach, while the members of such a federation would retain authority over local and national issues. The overall sovereignty over the world population would largely reside in the federal government.

References

- 1 2 3 KPFA Radio station (1954). KPFA folio. p. cclxxxii. Retrieved 18 September 2012.

- 1 2 Löwith, Mein Leben in Deutschland, p. 59.

- ↑ Marseille correspondence with Einstein, 1948. Marseille also told Einstein that Ralph Fox of Princeton University was a good friend, and the mathematician, Hans Rademacher, had been his teacher thirty years earlier in Germany (which would have been at the University of Berlin, or possibly, if after 1922, at Hamburg).

- ↑ Science: Handwriting as Character, Time , 25 May 1942

- ↑ The index was used in Rowena Wyant, "Voting via the Senate Mailbag", Public Opinion Quarterly 5 (1941): 359-82.

- ↑ Randerson, James (2008-10-10). "Einstein Letters Discussing Post-War Russia Go on Sale". The Guardian. Retrieved 2008-10-21.

- ↑ "Sale 664, 16th October 2008". Bloomsbury Auctions. Retrieved 2008-10-21.

- ↑ The letter may be read in R.W. Clark, The Life of Bertrand Russell, pp. 523–4; Russell, Selected Letters (ed. N. Griffin), vol. 2, pp. 428–9; Yours Faithfully, Bertrand Russell (ed. R. Perkins), pp. 204–5; Collected Papers of Bertrand Russell, vol. 28 (ed. A. Bone), p. 72; and it is discussed in Ray Monk's biography of Russell, vol. 2, pp. 299–303. Sidney Hook quoted the entire letter in his reply to M.S. Arnoni, "Arnoni vs. Hook", The New Leader, 23 Oct. 1967, pp. 34–5.