The officially stated goals of the foreign policy of the United States of America, including all the bureaus and offices in the United States Department of State, as mentioned in the Foreign Policy Agenda of the Department of State, are "to build and sustain a more democratic, secure, and prosperous world for the benefit of the American people and the international community". Liberalism has been a key component of US foreign policy since its independence from Britain. Since the end of World War II, the United States has had a grand strategy which has been characterized as being oriented around primacy, "deep engagement", and/or liberal hegemony. This strategy entails that the United States maintains military predominance; builds and maintains an extensive network of allies ; integrates other states into US-designed international institutions ; and limits the spread of nuclear weapons.

The diplomatic history of the United States oscillated among three positions: isolation from diplomatic entanglements of other nations ; alliances with European and other military partners; and unilateralism, or operating on its own sovereign policy decisions. The US always was large in terms of area, but its population was small, only 4 million in 1790. Population growth was rapid, reaching 7.2 million in 1810, 32 million in 1860, 76 million in 1900, 132 million in 1940, and 316 million in 2013. Economic growth in terms of overall GDP was even faster. However, the nation's military strength was quite limited in peacetime before 1940.

The Bush Doctrine refers to multiple interrelated foreign policy principles of the 43rd President of the United States, George W. Bush. These principles include unilateralism, preemptive war, and regime change.

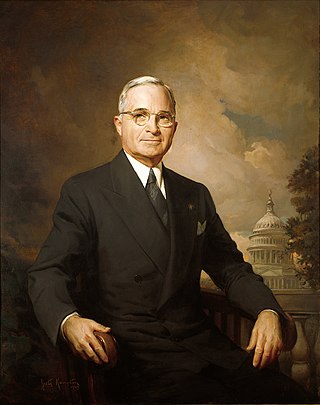

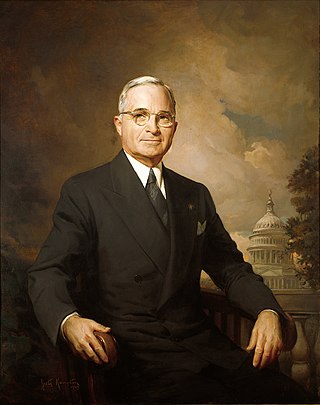

The Truman Doctrine is an American foreign policy that pledges American "support for democracies against authoritarian threats." The doctrine originated with the primary goal of countering the growth of the Soviet bloc during the Cold War. It was announced to Congress by President Harry S. Truman on March 12, 1947, and further developed on July 4, 1948, when he pledged to oppose the communist rebellions in Greece and Soviet demands from Turkey. More generally, the Truman Doctrine implied American support for other nations threatened by Moscow. It led to the formation of NATO in 1949. Historians often use Truman's speech to Congress on March 12, 1947 to date the start of the Cold War.

The Nixon Doctrine was put forth during a press conference in Guam on July 25, 1969, by President of the United States Richard Nixon and later formalized in his speech on Vietnamization of the Vietnam War on November 3, 1969. According to Gregg Brazinsky, author of "Nation Building in South Korea: Koreans, Americans, and the Making of a Democracy", Nixon stated that "the United States would assist in the defense and developments of allies and friends", but would not "undertake all the defense of the free nations of the world." This doctrine meant that each ally nation was in charge of its own security in general, but the United States would act as a nuclear umbrella when requested. The Doctrine argued for the pursuit of peace through a partnership with American allies.

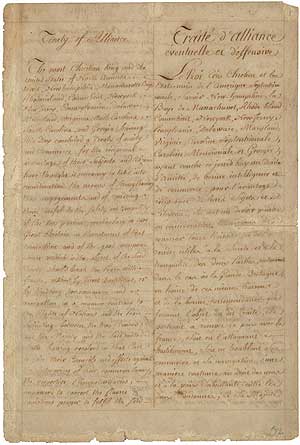

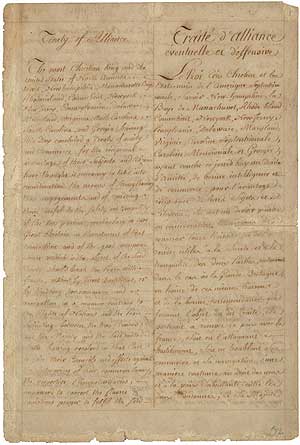

The Treaty of Alliance, also known as the Franco-American Treaty, was a defensive alliance between the Kingdom of France and the United States formed amid the American Revolutionary War with Great Britain. It was signed by delegates of King Louis XVI and the Second Continental Congress in Paris on February 6, 1778, along with the Treaty of Amity and Commerce and a secret clause providing for the entry of other European allies; together these instruments are sometimes known as the Franco-American Alliance or the Treaties of Alliance. The agreements marked the official entry of the United States on the world stage, and formalized French recognition and support of U.S. independence that was to be decisive in America's victory.

A United States presidential doctrine comprises the key goals, attitudes, or stances for United States foreign affairs outlined by a president. Most presidential doctrines are related to the Cold War. Though many U.S. presidents had themes related to their handling of foreign policy, the term doctrine generally applies to presidents such as James Monroe, Harry S. Truman, Richard Nixon, Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan, all of whom had doctrines which more completely characterized their foreign policy.

France was the first friendly country of the new United States in 1778. The 1778 Treaty of Alliance between the two countries and the subsequent aid provided from France proved decisive in the American victory over Britain in the American Revolutionary War. France, however, was left heavily indebted after the war, which contributed to France's own revolution and eventual transition to a republic.

United States non-interventionism primarily refers to the foreign policy that was eventually applied by the United States between the late 18th century and the first half of the 20th century whereby it sought to avoid alliances with other nations in order to prevent itself from being drawn into wars that were not related to the direct territorial self-defense of the United States. Neutrality and non-interventionism found support among elite and popular opinion in the United States, which varied depending on the international context and the country's interests. At times, the degree and nature of this policy was better known as isolationism, such as the interwar period.

Washington's Farewell Address is a letter written by President George Washington as a valedictory to "friends and fellow-citizens" after 20 years of public service to the United States. He wrote it near the end of the second term of his presidency before retiring to his home at Mount Vernon in Virginia.

The Kennedy Doctrine refers to foreign policy initiatives of the 35th President of the United States, John Fitzgerald Kennedy, towards Latin America during his administration between 1961 and 1963. Kennedy voiced support for the containment of communism as well as the reversal of communist progress in the Western Hemisphere.

Thomas Jefferson served as the third president of the United States from March 4, 1801, to March 4, 1809. Jefferson assumed the office after defeating incumbent John Adams in the 1800 presidential election. The election was a political realignment in which the Democratic-Republican Party swept the Federalist Party out of power, ushering in a generation of Jeffersonian Republican dominance in American politics. After serving two terms, Jefferson was succeeded by Secretary of State James Madison, also of the Democratic-Republican Party.

Wolfowitz Doctrine is an unofficial name given to the initial version of the Defense Planning Guidance for the 1994–1999 fiscal years published by U.S. Under Secretary of Defense for Policy Paul Wolfowitz and his deputy Scooter Libby. Not intended for public release, it was leaked to the New York Times on March 7, 1992, and sparked a public controversy about U.S. foreign and defense policy. The document was widely criticized as imperialist, as the document outlined a policy of unilateralism and pre-emptive military action to suppress potential threats from other nations and prevent dictatorships from rising to superpower status.

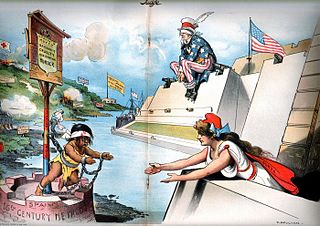

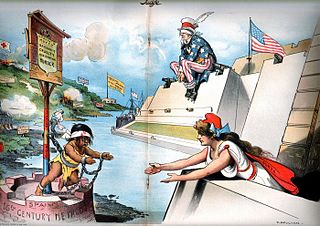

The Monroe Doctrine is a United States foreign policy position that opposes European colonialism in the Western Hemisphere. It holds that any intervention in the political affairs of the Americas by foreign powers is a potentially hostile act against the United States. The doctrine was central to American grand strategy in the 20th century.

In international relations, the term smart power refers to the combination of hard power and soft power strategies. It is defined by the Center for Strategic and International Studies as "an approach that underscores the necessity of a strong military, but also invests heavily in alliances, partnerships, and institutions of all levels to expand one's influence and establish legitimacy of one's action."

The Franco-American alliance was the 1778 alliance between the Kingdom of France and the United States during the American Revolutionary War. Formalized in the 1778 Treaty of Alliance, it was a military pact in which the French provided many supplies for the Americans. The Netherlands and Spain later joined as allies of France; Britain had no European allies. The French alliance was possible once the Americans captured a British invasion army at Saratoga in October 1777, demonstrating the viability of the American cause. The alliance became controversial after 1793 when Britain and Revolutionary France again went to war and the U.S. declared itself neutral. Relations between France and the United States worsened as the latter became closer to Britain in the Jay Treaty of 1795, leading to an undeclared Quasi War. The alliance was defunct by 1794 and formally ended in 1800.

The Obama Doctrine is used to describe one or several principles of the foreign policy of U.S. President Barack Obama. In 2015, during an interview with The New York Times, Obama said: "You asked about an Obama doctrine, the doctrine is we will engage, but we preserve all our capabilities".

The Empire of Liberty is a theme developed first by Thomas Jefferson to identify what he considered the responsibility of the United States to spread freedom across the world. Jefferson saw the mission of the U.S. in terms of setting an example, expansion into western North America, and by intervention abroad. Major exponents of the theme have been James Monroe, Andrew Jackson and James K. Polk, Abraham Lincoln, Theodore Roosevelt, Woodrow Wilson (Wilsonianism), Franklin D. Roosevelt, Harry Truman, Ronald Reagan, Bill Clinton, and George W. Bush.

History of United States foreign policy is a brief overview of major trends regarding the foreign policy of the United States from the American Revolution to the present. The major themes are becoming an "Empire of Liberty", promoting democracy, expanding across the continent, supporting liberal internationalism, contesting World Wars and the Cold War, fighting international terrorism, developing the Third World, and building a strong world economy with low tariffs.

The 1801 State of the Union Address was written by Thomas Jefferson, the third president of the United States, on Tuesday, December 8, 1801. It was his first annual address, and it was presented in Washington, D.C, by a clerk. He did not speak it to the 7th United States Congress, because he thought that would make him seem like a king. He said, "Whilst we devoutly return thanks to the beneficent Being who has been pleased to breathe into them the spirit of conciliation and forgiveness, we are bound with peculiar gratitude to be thankful to Him that our own peace has been preserved through so perilous a season, and ourselves permitted quietly to cultivate the earth and to practice and improve those arts which tend to increase our comforts." During the address Jefferson proclaimed the Washington Doctrine of Unstable Alliances.