Comic Relief is an operating British charity, founded in 1985 by the comedy scriptwriter Richard Curtis and comedian Sir Lenny Henry in response to the famine in Ethiopia. The concept of Comic Relief was to get British comedians to make the public laugh, while raising money to help people around the world and in the United Kingdom. A new CEO, Samir Patel, was announced in January 2021.

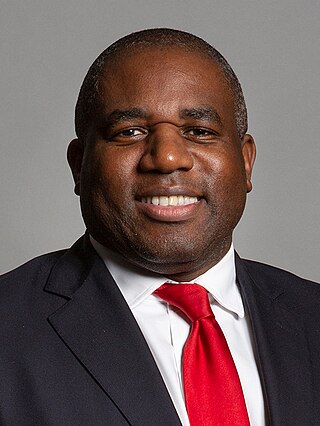

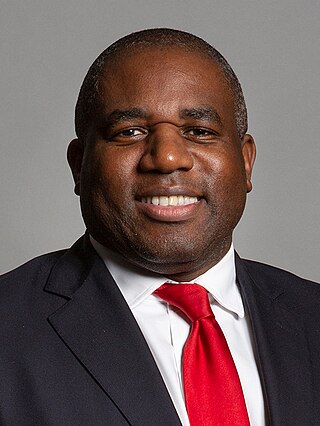

David Lammy is an English politician and lawyer serving as Shadow Secretary of State for Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Affairs since 2021. A member of the Labour Party, he has been Member of Parliament (MP) for Tottenham since the 2000 Tottenham by-election.

Slacktivism is the practice of supporting a political or social cause by means such as social media or online petitions, characterized as involving very little effort or commitment. Additional forms of slacktivism include engaging in online activities such as "liking," "sharing," or "tweeting" about a cause on social media, signing an Internet petition, copying and pasting a status or message in support of the cause, sharing specific hashtags associated with the cause, or altering one's profile photo or avatar on social network services to indicate solidarity.

In the United States, acting white is a pejorative term, usually applied to Black people, which refers to a person's perceived betrayal of their culture by assuming the social expectations of white society. It can be applied to success in education, but this view is highly debated. In 2020, 93.6% of African-Americans between 25 and 39 had a high school diploma, on par with the national average, though African-Americans have a higher tendency to drop out from college than their white peers.

Alice Sophia Eve is a British-American actress. The daughter of actors Trevor Eve and Sharon Maughan, she began her career with supporting roles in the films Hawking and Stage Beauty. Her other credits include Starter for 10 (2006), She's Out of My League (2010), Men in Black 3 (2012), Star Trek Into Darkness (2013), Before We Go (2014), Please Stand By (2017), Replicas (2018), and Bombshell (2019). On television, she has had recurring roles on HBO's Entourage (2011), Marvel's Iron Fist (2018), and Amazon Prime's The Power (2023).

Racial passing occurs when a person who is classified as a member of a racial group is accepted or perceived ("passes") as a member of another racial group.

"Stranger in the Village" is an essay by African-American novelist James Baldwin about his experiences in Leukerbad, Switzerland, after he nearly suffered a breakdown. The essay was originally published in Harper's Magazine, October 1953, and later in his 1955 collection, Notes of a Native Son.

The industrial complex is a socioeconomic concept wherein businesses become entwined in social or political systems or institutions, creating or bolstering a profit economy from these systems. Such a complex is said to pursue its own interests regardless of, and often at the expense of, the best interests of society and individuals. Businesses within an industrial complex may have been created to advance a social or political goal, but mostly profit when the goal is not reached. The industrial complex may profit financially, or ideologically, from maintaining socially detrimental or inefficient systems.

Invisible Children, Inc., founded in 2004, is an organization to increase awareness of the activities of the Lord's Resistance Army (LRA) in Central Africa, and its leader, Joseph Kony. Specifically, the group seeks to put an end to the practices of the LRA, which include abductions and abuse of children, and forcing them to serve as soldiers. To this end, Invisible Children urges the United States government to take military action in the central region of Africa. Invisible Children also operates as a charitable organization, soliciting donations and selling merchandise to raise money for its cause. The organization promotes its cause by dispensing films on the internet and presenting in high schools and colleges around the United States.

Teju Cole is a Nigerian-American writer, photographer, and art historian. He is the author of a novella, Every Day Is for the Thief (2007), a novel, Open City (2011), an essay collection, Known and Strange Things (2016), a photobook Punto d'Ombra, and a second novel, Tremor (2023). Critics have praised his work as having "opened a new path in African literature."

Kony 2012 is a 2012 American short documentary film produced by Invisible Children, Inc. The film's purpose was to make Ugandan cult leader, war criminal, and ICC fugitive Joseph Kony globally known so as to have him arrested by the end of 2012. The film was released on March 5, 2012, and spread virally, and the campaign was initially supported by various celebrities.

The term post-blackness is a philosophical movement with origins in the art world that attempts to reconcile the American understanding of race with the lived experiences of African Americans in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

The white savior is a cinematic trope in which a white central character rescues non-white characters from unfortunate circumstances. This recurs in an array of genres in American cinema, wherein a white protagonist is portrayed as a messianic figure who often gains some insight or introspection in the course of rescuing non-white characters from their plight.

Marvel's Iron Fist is an American television series created by Scott Buck for the streaming service Netflix, based on the Marvel Comics character Iron Fist. It is set in the Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU), sharing continuity with the franchise's films, and was the fourth Marvel Netflix series leading to the crossover miniseries The Defenders (2017). The series was produced by Marvel Television in association with ABC Studios, with Buck serving as showrunner for the first season and Raven Metzner taking over for the second.

Marvel's The Defenders is an American television miniseries created by Douglas Petrie and Marco Ramirez for the streaming service Netflix, based on the Marvel Comics characters Daredevil, Jessica Jones, Luke Cage, and Iron Fist, who form the eponymous superhero team. It is set in the Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU), sharing continuity with the franchise's films. The miniseries is a crossover event and the culmination for four previously released interconnected series from Marvel and Netflix. It was produced by Marvel Television in association with ABC Studios, Nine and a Half Fingers, Inc., and Goddard Textiles, with Ramirez serving as showrunner.

Get Out is a 2017 American psychological black horror film written, co-produced, and directed by Jordan Peele in his directorial debut. It stars Daniel Kaluuya, Allison Williams, Lil Rel Howery, LaKeith Stanfield, Bradley Whitford, Caleb Landry Jones, Stephen Root, and Catherine Keener. The plot follows a young black man (Kaluuya), who uncovers shocking secrets when he meets the family of his white girlfriend (Williams).

Hidden Figures is a 2016 American biographical drama film directed by Theodore Melfi and written by Melfi and Allison Schroeder. It is loosely based on the 2016 non-fiction book of the same name by Margot Lee Shetterly about three female African-American mathematicians: Katherine Goble Johnson, Dorothy Vaughan, and Mary Jackson, who worked at NASA during the Space Race. Other stars include Kevin Costner, Kirsten Dunst, Jim Parsons, Mahershala Ali, Aldis Hodge, and Glen Powell.

Louise Linton is a Scottish actress. She has appeared in the horror films Cabin Fever and Intruder, in minor roles in the television series CSI: NY and Cold Case, and wrote, directed, produced and starred in the 2021 film Me You Madness. Linton is married to Steven Mnuchin, the former United States Secretary of the Treasury.

The first season of the American streaming television series Iron Fist, which is based on the Marvel Comics character of the same name, follows Danny Rand as he returns to New York City after being presumed dead for 15 years and must choose between his family's legacy and his duties as the Iron Fist. It is set in the Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU), sharing continuity with the films and other television series of the franchise. The season was produced by Marvel Television in association with ABC Studios and Devilina Productions, with Scott Buck serving as showrunner.

Karen is a term used as slang typically for a middle-class white American woman who is perceived as entitled or excessively demanding beyond the scope of what is considered to be normal behavior and decorum. The term is often portrayed in memes depicting middle-class white women who "use their white and class privilege to demand their own way". Depictions include demanding to "speak to the manager", being racist, or wearing a particular bob cut hairstyle. It was popularized in the aftermath of the Central Park birdwatching incident in 2020.