The Copenhagen interpretation is a collection of views about the meaning of quantum mechanics, stemming from the work of Niels Bohr, Werner Heisenberg, Max Born, and others. The term "Copenhagen interpretation" was apparently coined by Heisenberg during the 1950s to refer to ideas developed in the 1925–1927 period, glossing over his disagreements with Bohr. Consequently, there is no definitive historical statement of what the interpretation entails.

The many-worlds interpretation (MWI) is a philosophical position about how the mathematics used in quantum mechanics relates to physical reality. It asserts that the universal wavefunction is objectively real, and that there is no wave function collapse. This implies that all possible outcomes of quantum measurements are physically realized in some "world" or universe. In contrast to some other interpretations, the evolution of reality as a whole in MWI is rigidly deterministic and local. Many-worlds is also called the relative state formulation or the Everett interpretation, after physicist Hugh Everett, who first proposed it in 1957. Bryce DeWitt popularized the formulation and named it many-worlds in the 1970s.

The Einstein–Podolsky–Rosen (EPR) paradox is a thought experiment proposed by physicists Albert Einstein, Boris Podolsky and Nathan Rosen which argues that the description of physical reality provided by quantum mechanics is incomplete. In a 1935 paper titled "Can Quantum-Mechanical Description of Physical Reality be Considered Complete?", they argued for the existence of "elements of reality" that were not part of quantum theory, and speculated that it should be possible to construct a theory containing these hidden variables. Resolutions of the paradox have important implications for the interpretation of quantum mechanics.

The mathematical formulations of quantum mechanics are those mathematical formalisms that permit a rigorous description of quantum mechanics. This mathematical formalism uses mainly a part of functional analysis, especially Hilbert spaces, which are a kind of linear space. Such are distinguished from mathematical formalisms for physics theories developed prior to the early 1900s by the use of abstract mathematical structures, such as infinite-dimensional Hilbert spaces, and operators on these spaces. In brief, values of physical observables such as energy and momentum were no longer considered as values of functions on phase space, but as eigenvalues; more precisely as spectral values of linear operators in Hilbert space.

Quantum mechanics is a fundamental theory in physics that describes the behavior of nature at and below the scale of atoms. It is the foundation of all quantum physics, which includes quantum chemistry, quantum field theory, quantum technology, and quantum information science.

In quantum mechanics, Schrödinger's cat is a thought experiment, sometimes described as a paradox, of quantum superposition. In the thought experiment, a hypothetical cat may be considered simultaneously both alive and dead, while it is unobserved in a closed box, as a result of its fate being linked to a random subatomic event that may or may not occur. This thought experiment was devised by physicist Erwin Schrödinger in 1935 in a discussion with Albert Einstein to illustrate what Schrödinger saw as the problems of the Copenhagen interpretation of quantum mechanics.

An interpretation of quantum mechanics is an attempt to explain how the mathematical theory of quantum mechanics might correspond to experienced reality. Although quantum mechanics has held up to rigorous and extremely precise tests in an extraordinarily broad range of experiments, there exist a number of contending schools of thought over their interpretation. These views on interpretation differ on such fundamental questions as whether quantum mechanics is deterministic or stochastic, local or non-local, which elements of quantum mechanics can be considered real, and what the nature of measurement is, among other matters.

In quantum mechanics, wave function collapse, also called reduction of the state vector, occurs when a wave function—initially in a superposition of several eigenstates—reduces to a single eigenstate due to interaction with the external world. This interaction is called an observation, and is the essence of a measurement in quantum mechanics, which connects the wave function with classical observables such as position and momentum. Collapse is one of the two processes by which quantum systems evolve in time; the other is the continuous evolution governed by the Schrödinger equation.

Quantum superposition is a fundamental principle of quantum mechanics that states that linear combinations of solutions to the Schrödinger equation are also solutions of the Schrödinger equation. This follows from the fact that the Schrödinger equation is a linear differential equation in time and position. More precisely, the state of a system is given by a linear combination of all the eigenfunctions of the Schrödinger equation governing that system.

Quantum decoherence is the loss of quantum coherence, the process in which a system's behaviour changes from that which can be explained by quantum mechanics to that which can be explained by classical mechanics. Beginning out of attempts to extend the understanding of quantum mechanics, the theory has developed in several directions and experimental studies have confirmed some of the key issues. Quantum computing relies on quantum coherence and is the primary practical applications of the concept.

The many-minds interpretation of quantum mechanics extends the many-worlds interpretation by proposing that the distinction between worlds should be made at the level of the mind of an individual observer. The concept was first introduced in 1970 by H. Dieter Zeh as a variant of the Hugh Everett interpretation in connection with quantum decoherence, and later explicitly called a many or multi-consciousness interpretation. The name many-minds interpretation was first used by David Albert and Barry Loewer in 1988.

In quantum mechanics, a probability amplitude is a complex number used for describing the behaviour of systems. The square of the modulus of this quantity represents a probability density.

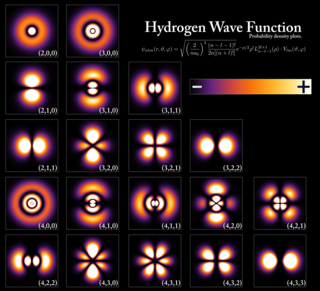

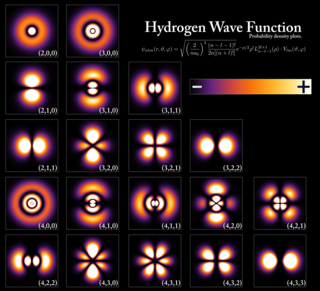

In quantum physics, a measurement is the testing or manipulation of a physical system to yield a numerical result. A fundamental feature of quantum theory is that the predictions it makes are probabilistic. The procedure for finding a probability involves combining a quantum state, which mathematically describes a quantum system, with a mathematical representation of the measurement to be performed on that system. The formula for this calculation is known as the Born rule. For example, a quantum particle like an electron can be described by a quantum state that associates to each point in space a complex number called a probability amplitude. Applying the Born rule to these amplitudes gives the probabilities that the electron will be found in one region or another when an experiment is performed to locate it. This is the best the theory can do; it cannot say for certain where the electron will be found. The same quantum state can also be used to make a prediction of how the electron will be moving, if an experiment is performed to measure its momentum instead of its position. The uncertainty principle implies that, whatever the quantum state, the range of predictions for the electron's position and the range of predictions for its momentum cannot both be narrow. Some quantum states imply a near-certain prediction of the result of a position measurement, but the result of a momentum measurement will be highly unpredictable, and vice versa. Furthermore, the fact that nature violates the statistical conditions known as Bell inequalities indicates that the unpredictability of quantum measurement results cannot be explained away as due to ignorance about "local hidden variables" within quantum systems.

In quantum mechanics, the measurement problem is the problem of definite outcomes: quantum systems have superpositions but quantum measurements only give one definite result.

The Born rule is a postulate of quantum mechanics that gives the probability that a measurement of a quantum system will yield a given result. In its simplest form, it states that the probability density of finding a system in a given state, when measured, is proportional to the square of the amplitude of the system's wavefunction at that state. It was formulated and published by German physicist Max Born in July, 1926.

Relational quantum mechanics (RQM) is an interpretation of quantum mechanics which treats the state of a quantum system as being relational, that is, the state is the relation between the observer and the system. This interpretation was first delineated by Carlo Rovelli in a 1994 preprint, and has since been expanded upon by a number of theorists. It is inspired by the key idea behind special relativity, that the details of an observation depend on the reference frame of the observer, and uses some ideas from Wheeler on quantum information.

The ensemble interpretation of quantum mechanics considers the quantum state description to apply only to an ensemble of similarly prepared systems, rather than supposing that it exhaustively represents an individual physical system.

The Ghirardi–Rimini–Weber theory (GRW) is a spontaneous collapse theory in quantum mechanics, proposed in 1986 by Giancarlo Ghirardi, Alberto Rimini, and Tullio Weber.

In quantum physics, a quantum state is a mathematical entity that embodies the knowledge of a quantum system. Quantum mechanics specifies the construction, evolution, and measurement of a quantum state. The result is a quantum-mechanical prediction for the system represented by the state. Knowledge of the quantum state, and the quantum mechanical rules for the system's evolution in time, exhausts all that can be known about a quantum system.

The von Neumann–Wigner interpretation, also described as "consciousness causes collapse", is an interpretation of quantum mechanics in which consciousness is postulated to be necessary for the completion of the process of quantum measurement.