Related Research Articles

Old English literature refers to poetry and prose written in Old English in early medieval England, from the 7th century to the decades after the Norman Conquest of 1066, a period often termed Anglo-Saxon England. The 7th-century work Cædmon's Hymn is often considered as the oldest surviving poem in English, as it appears in an 8th-century copy of Bede's text, the Ecclesiastical History of the English People. Poetry written in the mid 12th century represents some of the latest post-Norman examples of Old English. Adherence to the grammatical rules of Old English is largely inconsistent in 12th-century work, and by the 13th century the grammar and syntax of Old English had almost completely deteriorated, giving way to the much larger Middle English corpus of literature.

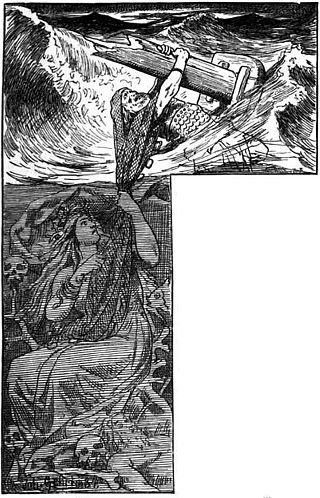

In Norse mythology, Rán is a goddess and a personification of the sea. Rán and her husband Ægir, a jötunn who also personifies the sea, have nine daughters, who personify waves. The goddess is frequently associated with a net, which she uses to capture sea-goers. According to the prose introduction to a poem in the Poetic Edda and in Völsunga saga, Rán once loaned her net to the god Loki.

Hávamál is presented as a single poem in the Icelandic Codex Regius, a collection of Old Norse poems from the Viking age. The poem, itself a combination of numerous shorter poems, is largely gnomic, presenting advice for living, proper conduct and wisdom. It is considered an important source of Old Norse philosophy.

In Norse mythology, the Vanir are a group of gods associated with fertility, wisdom, and the ability to see the future. The Vanir are one of two groups of gods and are the namesake of the location Vanaheimr. After the Æsir–Vanir War, the Vanir became a subgroup of the Æsir. Subsequently, members of the Vanir are sometimes also referred to as members of the Æsir.

In Norse mythology, Hlín is a goddess associated with the goddess Frigg. Hlín appears in a poem in the Poetic Edda, compiled in the 13th century from earlier traditional sources, the Prose Edda, written in the 13th century by Snorri Sturluson, and in kennings found in skaldic poetry. Scholars have debated whether the stanza referring to her in the Prose Edda refers to Frigg. Hlín serves as a given name in Iceland, and Hlín receives veneration in the modern era in Germanic paganism's modern extension, Heathenry.

In Norse mythology, Sif is a golden-haired goddess associated with earth. Sif is attested in the Poetic Edda, compiled in the 13th century from earlier traditional sources, and the Prose Edda, written in the 13th century by Snorri Sturluson, and in the poetry of skalds. In both the Poetic Edda and the Prose Edda, she is known for her golden hair and is married to the thunder god Thor.

The Poetic Edda is the modern name for an untitled collection of Old Norse anonymous narrative poems, which is distinct from the Prose Edda written by Snorri Sturluson. Several versions exist, all primarily of text from the Icelandic medieval manuscript known as the Codex Regius, which contains 31 poems. The Codex Regius is arguably the most important extant source on Norse mythology and Germanic heroic legends. Since the early 19th century, it has had a powerful influence on Scandinavian literature, not only through its stories, but also through the visionary force and the dramatic quality of many of the poems. It has also been an inspiration for later innovations in poetic meter, particularly in Nordic languages, with its use of terse, stress-based metrical schemes that lack final rhymes, instead focusing on alliterative devices and strongly concentrated imagery. Poets who have acknowledged their debt to the Codex Regius include Vilhelm Ekelund, August Strindberg, J. R. R. Tolkien, Ezra Pound, Jorge Luis Borges, and Karin Boye.

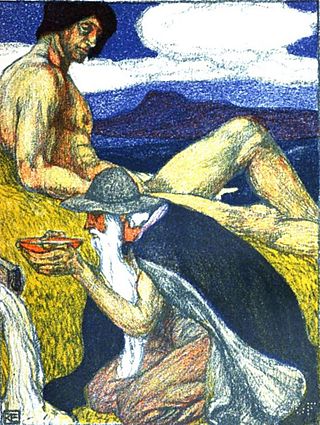

In Norse mythology, Óðr or Óð, sometimes anglicized as Odr or Od, is a figure associated with the major goddess Freyja. The Prose Edda and Heimskringla, written in the 13th century by Snorri Sturluson, both describe Óðr as Freyja's husband and father of her daughter Hnoss. Heimskringla adds that the couple produced another daughter, Gersemi. A number of theories have been proposed about Óðr, generally that he is a hypostasis of the deity Odin due to their similarities.

The Exeter Book, also known as the Codex Exoniensis or Exeter Cathedral Library MS 3501, is a large codex of Old English poetry, believed to have been produced in the late tenth century AD. It is one of the four major manuscripts of Old English poetry, along with the Vercelli Book in Vercelli, Italy, the Nowell Codex in the British Library, and the Junius manuscript in the Bodleian Library in Oxford. The book was donated to what is now the Exeter Cathedral library by Leofric, the first bishop of Exeter, in 1072. It is believed originally to have contained 130 or 131 leaves, of which the first 7 or 8 have been replaced with other leaves; the original first 8 leaves are lost. The Exeter Book is the largest and perhaps oldest known manuscript of Old English literature, containing about a sixth of the Old English poetry that has come down to us.

The Seafarer is an Old English poem giving a first-person account of a man alone on the sea. The poem consists of 124 lines, followed by the single word "Amen". It is recorded only at folios 81 verso – 83 recto of the tenth-century Exeter Book, one of the four surviving manuscripts of Old English poetry. It has most often, though not always, been categorised as an elegy, a poetic genre commonly assigned to a particular group of Old English poems that reflect on spiritual and earthly melancholy.

Wisdom literature is a genre of literature common in the ancient Near East. It consists of statements by sages and the wise that offer teachings about divinity and virtue. Although this genre uses techniques of traditional oral storytelling, it was disseminated in written form.

Dragons, or worms, are present in Germanic mythology and wider folklore, where they are often portrayed as large venomous serpents. Especially in later tales, however, they share many common features with other dragons in European mythology.

In Norse mythology, Líf and Lífþrasir, sometimes anglicized as Lif and Lifthrasir, female and male respectively, are two humans who are foretold to survive the events of Ragnarök by hiding in a wood called Hoddmímis holt and, after the flames have abated, to repopulate the newly risen and fertile world. Líf and Lífþrasir are mentioned in the Poetic Edda, which was compiled in the 13th century from earlier traditional sources, and the Prose Edda, written in the 13th century by Snorri Sturluson. Many scholars have speculated as to the underlying meaning and origins of the two names.

In Norse mythology, Mímisbrunnr is a well associated with the being Mímir, located beneath the world tree Yggdrasil. Mímisbrunnr is attested in the Poetic Edda, compiled in the 13th century from earlier traditional sources, and the Prose Edda, written in the 13th century by Snorri Sturluson. The well is located beneath one of three roots of the world tree Yggdrasil, a root that passes into the Jötunheimr where the primordial plane of Ginnungagap once existed. In addition, the Prose Edda relates that the water of the well contains much wisdom, and that Odin sacrificed one of his eyes to the well in exchange for a drink. In the Prose Edda, Mímisbrunnr is mentioned as one of three wells existing beneath three roots of Yggdrasil, the other two being Hvergelmir, located beneath a root in Niflheim, and Urðarbrunnr.

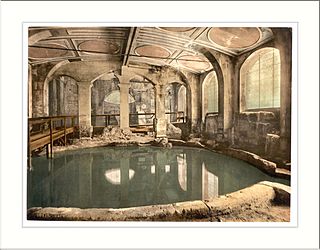

"The Ruin" is an elegy in Old English, written by an unknown author probably in the 8th or 9th century, and published in the 10th century in the Exeter Book, a large collection of poems and riddles. The poem evokes the former glory of an unnamed ruined ancient city that some scholars have identified with modern Bath, juxtaposing the grand, lively past with the decaying present.

Ím is a jötunn in Norse mythology, and the son of Vafthrudnir.

In Norse mythology, Mögþrasir is a jötunn who is solely attested in stanza 49 of the poem Vafþrúðnismál from the Poetic Edda.

The titles "Maxims I" and "Maxims II" refer to pieces of Old English gnomic poetry. The poem "Maxims I" can be found in the Exeter Book and "Maxims II" is located in a lesser known manuscript, London, British Library, Cotton Tiberius B i. "Maxims I" and "Maxims II" are classified as wisdom poetry, being both influenced by wisdom literature, such as the Psalms and Proverbs of the Old Testament scriptures. Although they are separate poems of diverse contents, they have been given a shared name because the themes throughout each poem are similar.

Ursula Miriam Dronke was a medievalist and former Vigfússon Reader in Old Norse at the University of Oxford and an Emeritus Fellow of Linacre College. She also taught at the University of Munich and in the Faculty of Modern and Medieval Languages at Cambridge University.

Carolyne Larrington is a Professor of Medieval European Literature and Official Fellow of St John's College at the University of Oxford. Her research has primarily been on Old Norse and medieval Arthurian literature. Her areas of focus have included how emotion and women are portrayed.

References

- ↑ Bullock, C. Hassell (2007). An Introduction to the Old Testament Poetic Books. Moody Publishers. ISBN 9781575674506.

- ↑ Mowinckel 1962, p. 105.

- ↑ Johnson, A. R. (1961). "The Psalms". In Rowley, H. H. (ed.). The Old Testament and Modern Study: A Generation of Discovery and Research. Oxford University Press. p. 177. OCLC 1245625555.

- ↑ Pagis 1991, pp. 15–16.

- ↑ Battles, Paul (2014). "Toward a Theory of Old English Poetic Genres: Epic, Elegy, Wisdom Poetry, and the "Traditional Opening"". Studies in Philology . 111 (1): 1–33. ISSN 0039-3738. JSTOR 24391997.

- 1 2 Olsen & Raffel 1998, p. 107.

- 1 2 Larrington 1993, p. 1.

- ↑ O'Camb, Brian (June 2009). "Bishop Æthelwold and the Shaping of the Old English Exeter Maxims". English Studies. 90 (3): 253–273. doi:10.1080/00138380902796714. ISSN 0013-838X. S2CID 162184922.