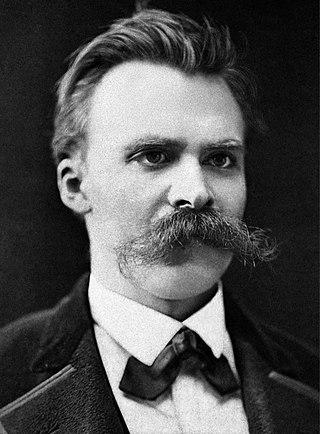

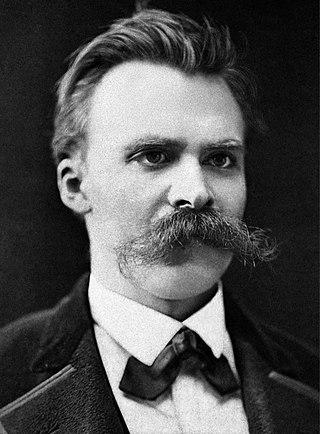

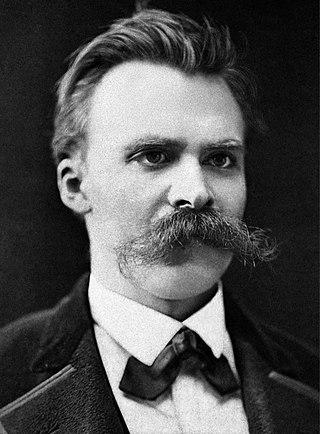

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche was a German philosopher. He began his career as a classical philologist before turning to philosophy. He became the youngest person to hold the Chair of Classical Philology at the University of Basel in 1869 at the age of 24, but resigned in 1879 due to health problems that plagued him most of his life; he completed much of his core writing in the following decade. In 1889, at age 44, he suffered a collapse and afterward a complete loss of his mental faculties, with paralysis and probably vascular dementia. He lived his remaining years in the care of his mother until her death in 1897 and then with his sister Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche. Nietzsche died in 1900, after experiencing pneumonia and multiple strokes.

German philosophy, meaning philosophy in the German language or philosophy by German people, in its diversity, is fundamental for both the analytic and continental traditions. It covers figures such as Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, Immanuel Kant, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Karl Marx, Friedrich Nietzsche, Martin Heidegger, Ludwig Wittgenstein, the Vienna Circle, and the Frankfurt School, who now count among the most famous and studied philosophers of all time. They are central to major philosophical movements such as rationalism, German idealism, Romanticism, dialectical materialism, existentialism, phenomenology, hermeneutics, logical positivism, and critical theory. The Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard is often also included in surveys of German philosophy due to his extensive engagement with German thinkers.

In the 19th century, the philosophers of the 18th-century Enlightenment began to have a dramatic effect on subsequent developments in philosophy. In particular, the works of Immanuel Kant gave rise to a new generation of German philosophers and began to see wider recognition internationally. Also, in a reaction to the Enlightenment, a movement called Romanticism began to develop towards the end of the 18th century. Key ideas that sparked changes in philosophy were the fast progress of science, including evolution, most notably postulated by Charles Darwin and Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, and theories regarding what is today called emergent order, such as the free market of Adam Smith within nation states, or the Marxist approach concerning class warfare between the ruling class and the working class developed by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Pressures for egalitarianism, and more rapid change culminated in a period of revolution and turbulence that would see philosophy change as well.

Continental philosophy is a term used to describe some philosophers and philosophical traditions that do not fall under the umbrella of analytic philosophy. However, there is no academic consensus on the definition of continental philosophy. Prior to the twentieth century, the term "continental" was used broadly to refer to philosophy from continental Europe. A different use of the term originated among English-speaking philosophers in the second half of the 20th century, who used it to refer to a range of thinkers and traditions outside the analytic movement. Continental philosophy includes German idealism, phenomenology, existentialism, hermeneutics, structuralism, post-structuralism, deconstruction, French feminism, psychoanalytic theory, and the critical theory of the Frankfurt School as well as branches of Freudian, Hegelian and Western Marxist views. There is widespread influence and debate between the analytic and continental traditions; some philosophers see the differences between the two traditions as being based on institutions, relationships, and ideology rather than anything of significant philosophical substance.

Karl Theodor Jaspers was a German-Swiss psychiatrist and philosopher who had a strong influence on modern theology, psychiatry, and philosophy. After being trained in and practising psychiatry, Jaspers turned to philosophical inquiry and attempted to discover an innovative philosophical system. He was often viewed as a major exponent of existentialism in Germany, though he did not accept the label.

Hans Vaihinger was a German philosopher, best known as a Kant scholar and for his Die Philosophie des Als Ob, published in 1911 although its statement of basic principles had been written more than thirty years earlier.

Hermann Cohen was a German Jewish philosopher, one of the founders of the Marburg school of neo-Kantianism, and he is often held to be "probably the most important Jewish philosopher of the nineteenth century".

Beyond Good and Evil: Prelude to a Philosophy of the Future is a book by philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche that covers ideas in his previous work Thus Spoke Zarathustra but with a more polemical approach. It was first published in 1886 under the publishing house C. G. Naumann of Leipzig at the author's own expense and first translated into English by Helen Zimmern, who was two years younger than Nietzsche and knew the author.

Walter Arnold Kaufmann was a German-American philosopher, translator, and poet. A prolific author, he wrote extensively on a broad range of subjects, such as authenticity and death, moral philosophy and existentialism, theism and atheism, Christianity and Judaism, as well as philosophy and literature. He served more than 30 years as a professor at Princeton University.

Paul Ludwig Carl Heinrich Rée was a German author, physician, philosopher, and friend of Friedrich Nietzsche.

Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900) developed his philosophy during the late 19th century. He owed the awakening of his philosophical interest to reading Arthur Schopenhauer's Die Welt als Wille und Vorstellung and said that Schopenhauer was one of the few thinkers that he respected, dedicating to him his essay Schopenhauer als Erzieher, published in 1874 as one of his Untimely Meditations.

Espen Hammer is Professor of Philosophy at Temple University. Focusing on modern European thought from Kant and Hegel to Adorno and Heidegger, Hammer’s research includes critical theory, Wittgenstein and ordinary language philosophy, phenomenology, German idealism, social and political theory, and aesthetics. He has also written widely on the philosophy of literature and taken a special interest in the question of temporality.

Karoline Friederike Louise Maximiliane von Günderrode was a German Romantic poet. She used the pen name Tian.

Knowledge and Human Interests is a 1968 book by the German philosopher Jürgen Habermas, in which the author discusses the development of the modern natural and human sciences. He criticizes Sigmund Freud, arguing that psychoanalysis is a branch of the humanities rather than a science, and provides a critique of the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche.

Andrew S. Bowie is Professor of Philosophy and German at Royal Holloway, University of London and Founding Director of the Humanities and Arts Research Centre (HARC).

Buddhist thought and Western philosophy include several parallels.

Yirmiyahu Yovel was an Israeli philosopher and public intellectual. He was Professor Emeritus of philosophy at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and at the New School for Social Research in New York. Yovel had also been a political columnist in Israel, cultural and political critic and a frequent presence in the media. Yovel was a laureate of the Israel Prize in philosophy and officier of the French order of the Palme académique. His books were translated into English, French, German, Spanish, Portuguese, Rumanian, Hebrew, Korean and Japanese. Yovel was married to Shoshana Yovel, novelist and community organizer, and they had a son, Jonathan Yovel, poet and law professor, and a daughter, Ronny, classical musician, TV host and family therapist.

Julian Padraic Young is an American philosopher and William R. Kenan Jr. Professor of Humanities at Wake Forest University. He is known for his expertise on post-Kantian philosophy.

Kristin Gjesdal is a Norwegian philosopher and Professor of Philosophy at Temple University. She is known for her expertise in the field of hermeneutics, nineteenth-century philosophy, aesthetics, and phenomenology. Gjesdal is a member of The Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters.

The philosophical ideas and thoughts of Edmund Burke, Thomas Carlyle, Johann Gottlieb Fichte, Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling, Søren Kierkegaard, Arthur Schopenhauer and Richard Wagner have been frequently described as Romantic.