Incest is human sexual activity between family members or close relatives. This typically includes sexual activity between people in consanguinity, and sometimes those related by affinity, adoption, or lineage. It is strictly forbidden and considered immoral in most societies, and can lead to an increased risk of genetic disorders in children.

A wife is a female in a marital relationship. A woman who has separated from her partner continues to be a wife until the marriage is legally dissolved with a divorce judgement. On the death of her partner, a wife is referred to as a widow. The rights and obligations of a wife in relation to her partner and her status in the community and in law vary between cultures and have varied over time.

Freeborn women in ancient Rome were citizens (cives), but could not vote or hold political office. Because of their limited public role, women are named less frequently than men by Roman historians. But while Roman women held no direct political power, those from wealthy or powerful families could and did exert influence through private negotiations. Exceptional women who left an undeniable mark on history include Lucretia and Claudia Quinta, whose stories took on mythic significance; fierce Republican-era women such as Cornelia, mother of the Gracchi, and Fulvia, who commanded an army and issued coins bearing her image; women of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, most prominently Livia and Agrippina the Younger, who contributed to the formation of Imperial mores; and the empress Helena, a driving force in promoting Christianity.

Leah appears in the Hebrew Bible as one of the two wives of the Biblical patriarch Jacob. Leah was Jacob's first wife, and the older sister of his second wife Rachel. She is the mother of Jacob's first son Reuben. She has three more sons, namely Simeon, Levi and Judah, but does not bear another son until Rachel offers her a night with Jacob in exchange for some mandrake root. Leah gives birth to two more sons after this, Issachar and Zebulun, and to Jacob's only daughter, Dinah.

In Islam, a mahram is a family member with whom marriage would be considered permanently unlawful (haram). One's spouse is also a mahram. A woman does not need to wear hijab around her mahram, and an adult male mahram may escort a woman on a journey, although an escort may not be obligatory.

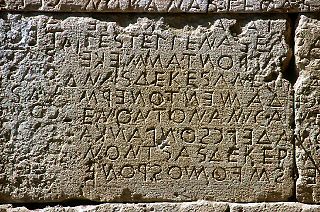

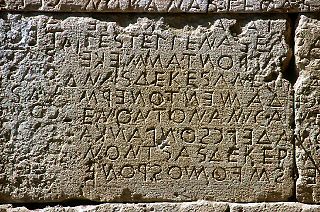

The legal rights of women refers to the social and human rights of women. One of the first women's rights declarations was the Declaration of Sentiments. The dependent position of women in early law is proved by the evidence of most ancient systems.

In Islam, nikah is a contract between two people. Both the groom and the bride are to consent to the marriage of their own free wills. A formal, binding contract – verbal or on paper – is considered integral to a religiously valid Islamic marriage, and outlines the rights and responsibilities of the groom and bride. Divorce in Islam can take a variety of forms, some executed by a husband personally and some executed by a religious court on behalf of a plaintiff wife who is successful in her legal divorce petition for valid cause.

The Algerian Family Code, enacted on June 9, 1984, specifies the laws relating to familial relations in Algeria. It includes strong elements of Islamic law which have brought it praise from Islamists and condemnation from secularists and feminists.

Traditional Chinese marriage is a ceremonial ritual within Chinese societies that involves not only a union between spouses, but also a union between the two families of a man and a woman, sometimes established by pre-arrangement between families. Marriage and family are inextricably linked, which involves the interests of both families. Within Chinese culture, romantic love and monogamy was the norm for most citizens. Around the end of primitive society, traditional Chinese marriage rituals were formed, with deer skin betrothal in the Fuxi era, the appearance of the "meeting hall" during the Xia and Shang dynasties, and then in the Zhou dynasty, a complete set of marriage etiquette gradually formed. The richness of this series of rituals proves the importance the ancients attached to marriage. In addition to the unique nature of the "three letters and six rituals", monogamy, remarriage and divorce in traditional Chinese marriage culture are also distinctive.

Jewish views on incest deal with the sexual relationships which are prohibited by Judaism and rabbinic authorities on account of a close family relationship that exists between persons. Such prohibited relationships are commonly referred to as incest or incestuous, though that term does not appear in the biblical and rabbinic sources. The term mostly used by rabbinic sources is "forbidden relationships in Judaism."

Boran was Sasanian queen of Iran from 630 to 632, with an interruption of some months. She was the daughter of king Khosrow II and the Byzantine princess Maria. She is the second of only three women to rule in Iranian history, the others being Musa of Parthia, and Boran's sister Azarmidokht.

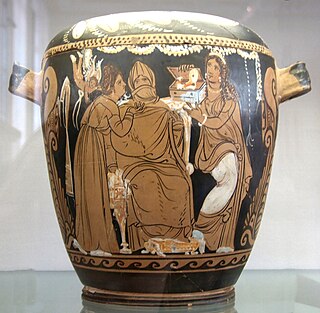

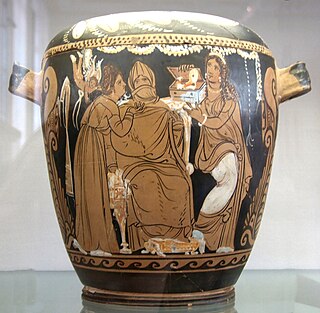

An epikleros was an heiress in ancient Athens and other ancient Greek city states, specifically a daughter of a man who had no sons. In Sparta, they were called patrouchoi (πατροῦχοι), as they were in Gortyn. Athenian women were not allowed to hold property in their own name; in order to keep her father's property in the family, an epikleros was required to marry her father's nearest male relative. Even if a woman was already married, evidence suggests that she was required to divorce her spouse to marry that relative. Spartan women were allowed to hold property in their own right, and so Spartan heiresses were subject to less restrictive rules. Evidence from other city-states is more fragmentary, mainly coming from the city-states of Gortyn and Rhegium.

Islamic Inheritance jurisprudence is a field of Islamic jurisprudence that deals with inheritance, a topic that is prominently dealt with in the Qur'an. It is often called Mīrāth, and its branch of Islamic law is technically known as ʿilm al-farāʾiḍ.

Sıla is a Turkish television series directed by Gül Oğuz for ATV and ATV Avrupa (Europe) in 2006. On September 15, 2006, ATV started broadcasting Sila. The last episode was broadcast on September 20, 2008.

Azarmidokht was Sasanian queen regnant (banbishn) of Iran from 630 to 631. She was the daughter of king (shah) Khosrow II. She was the second Sasanian queen; her sister Boran ruled before and after her. Azarmidokht came to power in Iran after her cousin Shapur-i Shahrvaraz was deposed by the Parsig faction, led by Piruz Khosrow, who helped Azarmidokht ascend the throne. Her rule was marked by an attempt of a nobleman and commander Farrukh Hormizd to marry her and come to power. After the queen's refusal, he declared himself an anti-king. Azarmidokht had him killed as a result of a successful plot. She was, however, killed herself shortly afterwards by Rostam Farrokhzad in retaliation for his father's death. She was succeeded by Boran.

Naming conventions for women in ancient Rome differed from nomenclature for men, and practice changed dramatically from the Early Republic to the High Empire and then into Late Antiquity. Females were identified officially by the feminine of the family name, which might be further differentiated by the genitive form of the father's cognomen, or for a married woman her husband's. Numerical adjectives might distinguish among sisters, such as Tertia, "the Third". By the late Republic, women also often adopted the feminine of their father's cognomen.

The Mundugumora.k.a.Biwat are a tribe of Papua New Guinea. They live on the Yuat River in East Sepik Province, Papua New Guinea, and speak the Mundugumor language.

Women in ancient Egypt had some special rights other women did not have in other comparable societies. They could own property and were, at court, legally equal to men. However, Ancient Egypt was a society dominated by men. Only a few women are known to have important positions in administration, though there were female rulers and even female pharaohs. Women at the royal court gained their positions by relationship to male kings.

Xwedodah is a spiritually-influenced style of consanguine marriage assumed to have been historically practiced in Zoroastrianism before the Muslim conquest of Persia. Such marriages are recorded as having been inspired by Zoroastrian cosmogony and considered pious, though little academic and religious consensus has been established as to the extent of the practice of Xwedodah outside of the aristocracy and clergy of the Sasanian Empire. In modern Zoroastrianism it is near non-existent, having been noted to have disappeared as an extant practice by the 11th century AD.

Marriage in ancient Greece had less of a basis in personal relationships and more in social responsibility. The goal and focus of all marriages was intended to be reproduction, making marriage an issue of public interest. Marriages were usually arranged by the parents; on occasion professional matchmakers were used. Each city was politically independent and each had its own laws concerning marriage. For the marriage to be legal, the woman's father or guardian gave permission to a suitable man who could afford to marry. Orphaned daughters were usually married to uncles or cousins. Wintertime marriages were popular due to the significance of that time to Hera, the goddess of marriage. The couple participated in a ceremony which included rituals such as veil removal, but it was the couple living together that made the marriage legal. Marriage was understood to be the official transition from childhood into adulthood for women.