Hatha yoga is a branch of yoga that uses physical techniques to try to preserve and channel vital force or energy. The Sanskrit word हठ haṭha literally means "force", alluding to a system of physical techniques. Some hatha yoga style techniques can be traced back at least to the 1st-century CE, in texts such as the Hindu Sanskrit epics and Buddhism's Pali canon. The oldest dated text so far found to describe hatha yoga, the 11th-century Amṛtasiddhi, comes from a tantric Buddhist milieu. The oldest texts to use the terminology of hatha are also Vajrayana Buddhist. Hindu hatha yoga texts appear from the 11th century onward.

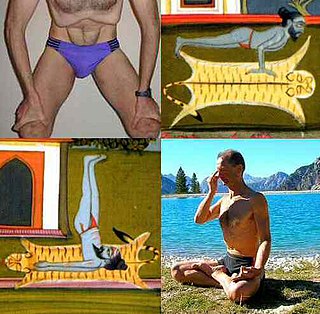

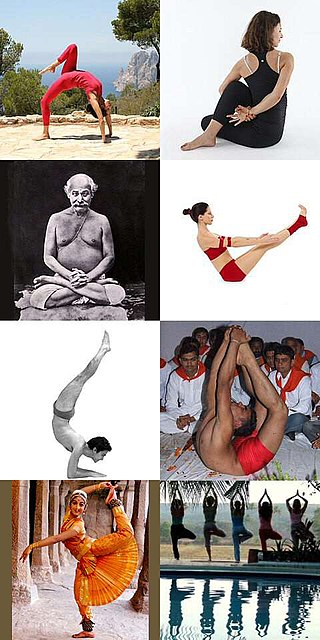

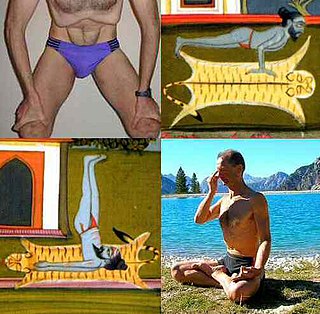

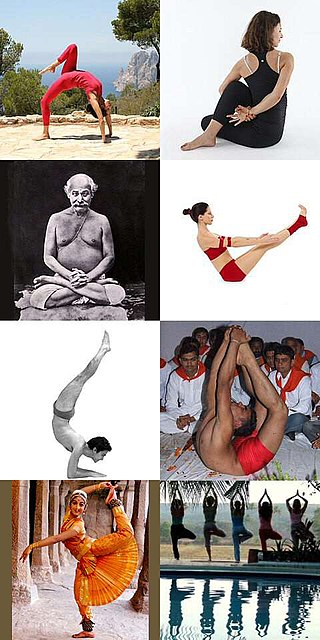

An āsana is a body posture, originally and still a general term for a sitting meditation pose, and later extended in hatha yoga and modern yoga as exercise, to any type of position, adding reclining, standing, inverted, twisting, and balancing poses. The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali define "asana" as "[a position that] is steady and comfortable". Patanjali mentions the ability to sit for extended periods as one of the eight limbs of his system. Asanas are also called yoga poses or yoga postures in English.

The Haṭha Yoga Pradīpikā is a classic fifteenth-century Sanskrit manual on haṭha yoga, written by Svātmārāma, who connects the teaching's lineage to Matsyendranath of the Nathas. It is among the most influential surviving texts on haṭha yoga, being one of the three classic texts alongside the Gheranda Samhita and the Shiva Samhita.

Halasana or Plough pose is an inverted asana in hatha yoga and modern yoga as exercise. Its variations include Karnapidasana with the knees by the ears, and Supta Konasana with the feet wide apart.

Vishnudevananda Saraswati was an Indian yoga guru known for his teaching of asanas, a disciple of Sivananda Saraswati, and founder of the International Sivananda Yoga Vedanta Centres and Ashrams. He established the Sivananda Yoga Teachers' Training Course, possibly the first yoga teacher training programs in the West. His books The Complete Illustrated Book of Yoga (1960) and Meditation and Mantras (1978) established him as an authority on Hatha and Raja yoga. Vishnudevananda was a peace activist who rode in several "peace flights" over places of conflict, including the Berlin Wall prior to German reunification.

Sivananda Yoga is a spiritual yoga system founded by Vishnudevananda; it includes the use of asanas but is not limited to them as in systems of yoga as exercise. He named this system, as well as the international Sivananda Yoga Vedanta Centres organization responsible for propagating its teachings, after his guru, Sivananda with the mission 'to spread the teachings of yoga and the message of world peace' which has since been refined to 'practice and teach the ancient yogic knowledge for health, peace, unity in diversity and self-realization.'

The Complete Illustrated Book of Yoga is a bestselling 1960 book by Swami Vishnudevananda, the founder of the Sivananda Yoga Vedanta Centres. It is an introduction to Hatha yoga, describing the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali and the Hatha Yoga Pradipika. It contributed to the incorporation of Surya Namaskar into yoga as exercise. While some of its subject matter is the traditional philosophy of yoga, its detailed photographs of Vishnudevananda performing the asanas is modern, helping to market the Sivananda yoga brand to a global audience.

Bakasana, and the similar Kakasana are balancing asanas in hatha yoga and modern yoga as exercise. In all variations, these are arm balancing poses in which hands are planted on the floor, shins rest upon upper arms, and feet lift up. The poses are often confused, but traditionally Kakasana has arms bent, Bakasana has the arms straight.

Salabhasana or Purna Salabhasana, Locust pose, or Grasshopper pose is a prone back-bending asana in modern yoga as exercise.

Siddhasana or Accomplished Pose is an ancient seated asana in hatha yoga and modern yoga as exercise suitable for meditation. The names Muktasana and Burmese position are sometimes given to the same pose, sometimes to an easier variant, Ardha Siddhasana. Svastikasana has each foot tucked as snugly as possible into the fold of the opposite knee.

Shavasana, Corpse Pose, or Mritasana, is an asana in hatha yoga and modern yoga as exercise, often used for relaxation at the end of a session. It is the usual pose for the practice of yoga nidra meditation, and is an important pose in Restorative Yoga.

Selvarajan Yesudian or Selva Raja Yesudian was a yoga teacher and author. He is in particular known for a book he co-authored with Elisabeth Haich: Sport és Jóga - Budapest 1941, Sport und Yoga 1949, in English-speaking countries released as Yoga and Health.

Baddha Konasana, Bound Angle Pose, Butterfly Pose, or Cobbler's Pose, and historically called Bhadrasana, Throne Pose, is a seated asana in hatha yoga and modern yoga as exercise. If the knees rest on the floor, it is suitable as a meditation seat.

Yoganidrasana, or Yogic Sleep Pose is a reclining forward-bending asana in modern yoga as exercise. It is sometimes called Supta Garbhasana. The name Dvi Pada Sirsasana is given to the balancing form of the pose.

Yoga as exercise is a physical activity consisting mainly of postures, often connected by flowing sequences, sometimes accompanied by breathing exercises, and frequently ending with relaxation lying down or meditation. Yoga in this form has become familiar across the world, especially in the US and Europe. It is derived from medieval Haṭha yoga, which made use of similar postures, but it is generally simply called "yoga". Academics have given yoga as exercise a variety of names, including modern postural yoga and transnational anglophone yoga.

Vajroli mudra, the Vajroli Seal, is a practice in Hatha yoga which requires the yogi to preserve his semen, either by learning not to release it, or if released by drawing it up through his urethra from the vagina of "a woman devoted to the practice of yoga".

Yoga teacher training is the training of teachers of yoga as exercise, consisting mainly of the practice of yoga asanas, leading to certification. Such training is accredited by the Yoga Alliance in America, by the British Wheel of Yoga in the United Kingdom, and by the European Union of Yoga across Europe. The Yoga Alliance sets standards for 200-hour and 500-hour Recognized Yoga Teacher levels, which are accepted in America and other countries.

Postural yoga began in India as a variant of traditional yoga, which was a mainly meditational practice; it has spread across the world and returned to the Indian subcontinent in different forms. The ancient Yoga Sutras of Patanjali mention yoga postures, asanas, only briefly, as meditation seats. Medieval Haṭha yoga made use of a small number of asanas alongside other techniques such as pranayama, shatkarmas, and mudras, but it was despised and almost extinct by the start of the 20th century. At that time, the revival of postural yoga was at first driven by Indian nationalism. Advocates such as Yogendra and Kuvalayananda made yoga acceptable in the 1920s, treating it as a medical subject. From the 1930s, the "father of modern yoga" Krishnamacharya developed a vigorous postural yoga, influenced by gymnastics, with transitions (vinyasas) that allowed one pose to flow into the next.

Hans-Ulrich Rieker was a German actor, author, and leader of the Buddhist religious order Arya Maitreya Mandala in Europe.