Alexander Joy Cartwright Jr. was a founding member of the New York Knickerbockers Base Ball Club in the 1840s. Although he was an inductee of the Baseball Hall of Fame and he was sometimes referred to as a "father of baseball", the importance of his role in the development of the game has been disputed.

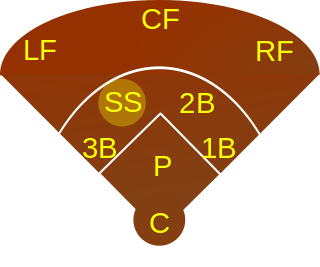

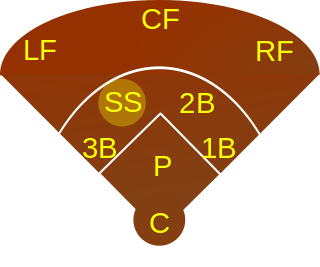

Shortstop, abbreviated SS, is the baseball or softball fielding position between second and third base, which is considered to be among the most demanding defensive positions. Historically the position was assigned to defensive specialists who were typically poor at batting and were often placed at the bottom of the batting order. Today, shortstops are often able to hit well and many are placed at the top of the lineup. In the numbering system used by scorers to record defensive plays, the shortstop is assigned the number 6.

The question of the origins of baseball has been the subject of debate and controversy for more than a century. Baseball and the other modern bat, ball, and running games — stoolball, cricket and rounders — were developed from folk games in early Britain, Ireland, and Continental Europe. Early forms of baseball had a number of names, including "base ball", "goal ball", "round ball", "fetch-catch", "stool ball", and, simply, "base". In at least one version of the game, teams pitched to themselves, runners went around the bases in the opposite direction of today's game, much like in the Nordic brännboll, and players could be put out by being hit with the ball. Just as now, in some versions a batter was called out after three strikes.

George Wright was an American shortstop in professional baseball. He played for the 1869 Cincinnati Red Stockings, the first fully professional team, when he was the game's best player. He then played for the Boston Red Stockings, helping the team win six league championships from 1871 to 1878. His older brother Harry Wright managed both Red Stockings teams and made George his cornerstone. George was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1937. After arriving in Boston, he also entered the sporting goods business. There he continued in the industry, assisting in the development of golf.

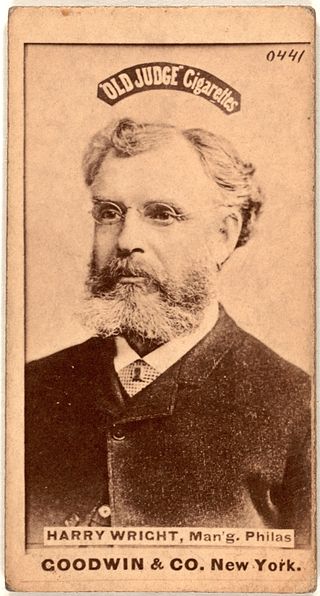

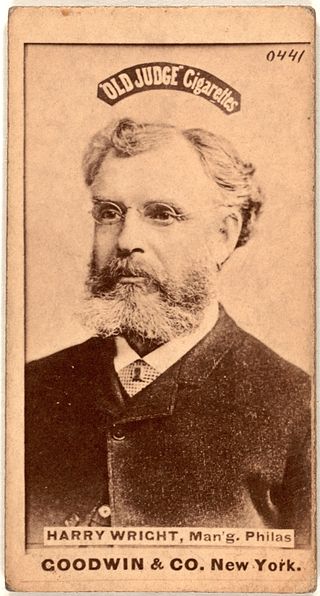

William Henry "Harry" Wright was an English-born professional baseball player, manager, and developer. He assembled, managed, and played center field for baseball's first fully professional team, the 1869 Cincinnati Red Stockings. He is credited with introducing innovations such as backing up infield plays from the outfield and shifting defensive alignments based on hitters' tendencies. For his contributions as a manager and developer of the game, he was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1953 by the Veterans Committee. Wright was also the first to make baseball into a business by paying his players up to seven times the pay of the average working man.

Town ball, townball, or Philadelphia town ball, is a bat-and-ball, safe haven game played in North America in the 18th and 19th centuries, which was similar to rounders and was a precursor to modern baseball. In some areas—such as Philadelphia and along the Ohio River and Mississippi River—the local game was called Town Ball. In other regions the local game was named "base", "round ball", "base ball", or just "ball"; after the development of the "New York game" in the 1840s it was sometimes distinguished as the "New England game" or "Massachusetts baseball". The players might be schoolboys in a pasture with improvised balls and bats, or young men in organized clubs. As baseball became dominant, town ball became a casual term to describe old fashioned or rural games similar to baseball.

James Creighton, Jr. was an American baseball player during the game's amateur era, and is considered by historians to be the sport's first superstar and one of its earliest paid competitors. In 1860 and 1862 he played for one of the most dominant teams of the era, the Excelsior of Brooklyn. He also was reputed to be a superb cricketer, and played in many amateur and professional cricket matches.

The New York Knickerbockers were one of the first organized baseball teams which played under a set of rules similar to the game today. Founded as the "Knickerbocker Base Ball Club" by Alexander Cartwright in 1845, the team remained active until the early 1870s.

The Knickerbocker Rules are a set of baseball rules formalized by William R. Wheaton and William H. Tucker of the Knickerbocker Base Ball Club in 1845. They have previously been considered to be the basis for the rules of the modern game, although this is disputed. The rules are informally known as the "New York style" of baseball, as opposed to other variants such as the "Massachusetts Game" and "Philadelphia town ball".

The Elysian Fields in Hoboken, New Jersey, was recreational parkland located on the city's northern riverfront in the 19th century. The area was a popular getaway destination for New Yorkers in the 19th century, much in the tradition of the pleasure garden, offering open space for a variety of sports, public spectacles, and amusements. The lavish grounds hosted the Colonnade Hotel and tavern, and offered picnic areas, a spa known as Sybil's Cave, river walks, nature paths, fishing, a miniature railroad, rides and races, and a ferry landing, which also served as a launch for boating competitions.

The following are the baseball events of the years 1845 to 1868 throughout the world.

Eckford of Brooklyn, or simply Eckford, was an American baseball club from 1855 to 1872. When the Union Grounds opened on May 15, 1862 for baseball in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, it became the first enclosed baseball grounds in America. Three clubs called the field on the corner of Marcy Avenue and Rutledge Street home; however, the Eckford of Brooklyn were the most famous tenant. They played more games than any other club that year (7) and won the "national" championship, repeating the feat in 1863. During that two year period, the Eckfords won 22 straight matches which was the longest undefeated and untied streak to date. In the late 1860s, they were one of the pioneering professional clubs, although probably second to Mutual of New York at the home park. In its final season, Eckford entered the second championship of the National Association, the first professional baseball league in America, so it is considered a major league club by those who count the NA as a major league.

John Van Buskirk Hatfield was an American professional baseball player in the 1860s and 1870s. He was a batting star and versatile fielder for the Mutual Base Ball Club both before and after spending the 1868 season as left fielder for Harry Wright's Cincinnati Red Stockings. Left field was his primary position during four years as a regular player in the major leagues from 1871. For a few decades after leaving the game he was famous for his "world record" long-distance throw. During an 1868 exhibition at Cincinnati's Union Grounds he threw the baseball 132 yards. On October 15, 1872 Hatfield threw a baseball 400 feet.

The Enterprise Base Ball Club of Brooklyn was an American baseball club in the 1850s and 1860s.

Daniel Lucius "Doc" Adams was an American baseball player and executive who is regarded by historians as an important figure in the sport's early years. For most of his career he was a member of the New York Knickerbockers. He first played for the New York Base Ball Club in 1840 and started his Knickerbockers career five years later, continuing to play for the club into his forties and to take part in inter-squad practice games and matches against opposing teams. Researchers have called Adams the creator of the shortstop position, which he used to field short throws from outfielders. In addition to his playing career, Adams manufactured baseballs and oversaw bat production; he also occasionally acted as an umpire.

William Rufus Wheaton was an American lawyer and politician. He was also a baseball pioneer.

Duncan Fraser Curry was an American baseball pioneer and insurance executive.

The Doubleday myth is the claim that the sport of baseball was invented in 1839 by future American Civil War general Abner Doubleday in Cooperstown, New York. In response to a dispute over whether baseball originated in the United States or was a variation of the British game rounders, the Mills Commission was formed in 1905 to seek out evidence. Mining engineer Abner Graves authored a letter claiming that Doubleday invented baseball. The letter was published in a newspaper and eventually used by the Mills Commission to support its finding that the game was of American origin. In 1908, it named Doubleday the creator of baseball.

Francis Pidgeon Sr. was an American baseball pitcher. He played for Eckford of Brooklyn from 1855 to 1862, and was one of the club's founders. Pidgeon has been called one of the top pitchers of the era, and participated in New York-area all-star games in 1858. Playing as an amateur, Pidgeon vigorously opposed payments to baseball players and authored a law banning them in the National Association of Base Ball Players (NABBP). After professionalism began spreading, he left the Eckford club before sponsoring an unsuccessful resolution opposing player pay in 1870. Pidgeon worked as a contractor before being hit by a train and killed in 1884.

William H. Tucker was an American baseball pioneer, who was a player and organizer with the New York Knickerbockers in the 1840s.