Related Research Articles

The Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU), also known by various other names during its history, was the founding and ruling party of the Soviet Union. The CPSU was the sole governing party of the Soviet Union until 1990 when the Congress of People's Deputies modified Article 6 of the 1977 Soviet Constitution, which had previously granted the CPSU a monopoly over the political system.

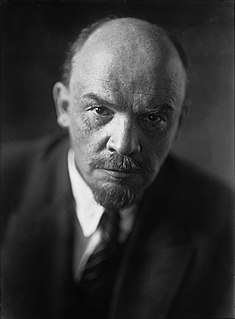

Leninism is a political ideology developed by Russian Marxist revolutionary Vladimir Lenin that proposes the establishment of the dictatorship of the proletariat led by a revolutionary vanguard party, as the political prelude to the establishment of communism. The function of the Leninist vanguard party is to provide the working classes with the political consciousness and revolutionary leadership necessary to depose capitalism in the Russian Empire (1721–1917). Leninist revolutionary leadership is based upon The Communist Manifesto (1848) identifying the communist party as "the most advanced and resolute section of the working class parties of every country; that section which pushes forward all others." As the vanguard party, the Bolsheviks viewed history through the theoretical framework of dialectical materialism, which sanctioned political commitment to the successful overthrow of capitalism, and then to instituting socialism; and, as the revolutionary national government, to realize the socio-economic transition by all means.

Marxism–Leninism is a communist ideology which was the main communist movement throughout the 20th century. It was the formal name of the state ideology adopted by the Soviet Union, its satellite states in the Eastern Bloc, and various scientific socialist countries in the Non-Aligned Movement and Third World during the Cold War as well as the Communist International after Bolshevisation. Today, Marxism–Leninism is the ideology of several communist parties, despite the de-Leninization that occurred after the dissolution of the USSR, and remains the official ideology of the ruling parties of China, Cuba, Laos, and Vietnam as one-party socialist republics, and of Nepal in a multiparty democracy.

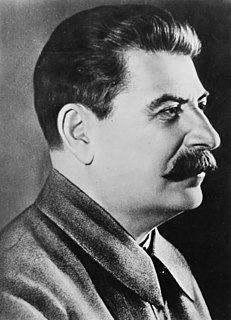

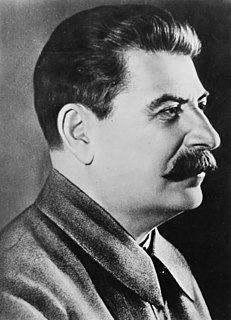

Stalinism is the means of governing and Marxist-Leninist policies implemented in the Soviet Union from 1927 to 1953 by Joseph Stalin. It included the creation of a one-party totalitarian police state, rapid industrialization, the theory of socialism in one country, collectivization of agriculture, intensification of class conflict, a cult of personality, and subordination of the interests of foreign communist parties to those of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, deemed by Stalinism to be the leading vanguard party of communist revolution at the time. De-Stalinization began in the 50's and 60's after the Krushchev thaw.

A communist party is a political party that seeks to realize the socio-economic goals of communism. The term communist party was popularized by the title of The Manifesto of the Communist Party (1848) by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. As a vanguard party, the communist party guides the political education and development of the working class (proletariat). As a ruling party, the communist party exercises power through the dictatorship of the proletariat. Vladimir Lenin developed the idea of the communist party as the revolutionary vanguard, when the socialist movement in Imperial Russia was divided into ideologically opposed factions, the Bolshevik faction and the Menshevik faction. To be politically effective, Lenin proposed a small vanguard party managed with democratic centralism which allowed centralized command of a disciplined cadre of professional revolutionaries. Once a policy was agreed upon, realizing political goals required every Bolshevik's total commitment to the agreed-upon policy.

Trotskyism is the political ideology and branch of Marxism developed by Ukrainian-Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky and by some other members of the Left Opposition and Fourth International. Trotsky self-identified as an orthodox Marxist, a revolutionary Marxist, and Bolshevik–Leninist, a follower of Marx, Engels, and of 3L: Vladimir Lenin, Karl Liebknecht, Rosa Luxemburg. He supported founding a vanguard party of the proletariat, proletarian internationalism, and a dictatorship of the proletariat based on working class self-emancipation and mass democracy. Trotskyists are critical of Stalinism as they oppose Joseph Stalin's theory of socialism in one country in favor of Trotsky's theory of permanent revolution. Trotskyists also criticize the bureaucracy and anti-democratic current that developed in the Soviet Union under Stalin.

The ten years 1917–1927 saw a radical transformation of the Russian Empire into a socialist state, the Soviet Union. Soviet Russia covers 1917–1922 and Soviet Union covers the years 1922 to 1991. After the Russian Civil War (1917–1923), the Bolsheviks took control. They were dedicated to a version of Marxism developed by Vladimir Lenin. It promised the workers would rise, destroy capitalism, and create a socialist society under the leadership of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. The awkward problem was the small proletariat, in an overwhelmingly peasant society with limited industry and a very small middle class. Following the February Revolution in 1917 that deposed Nicholas II of Russia, a short-lived provisional government gave way to Bolsheviks in the October Revolution. The Bolshevik Party was renamed the Russian Communist Party (RCP).

Agitprop refers to an intentional, vigorous promulgation of ideas. The term originated in Soviet Russia where it referred to popular media, such as literature, plays, pamphlets, films, and other art forms, with an explicitly political message in favor of communism.

The General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union was the head of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU). From 1929 until the union's dissolution, the holder of the office was the de facto leader of the Soviet Union, because the post controlled the party, the foreign and internal politic of the state and the federal government. It was the de facto highest ranking office of the Union.

Lazar Moiseyevich Kaganovich, also Kahanovich, was a Soviet politician and administrator, and one of the main associates of Joseph Stalin. He is known for helping Stalin come to power and for his harsh treatment and execution of those deemed threats to Stalin's regime.

The history of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union was generally perceived as covering that of the Bolshevik faction of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party from which it evolved. The date 1912 is often identified as the time of the formation of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union as a distinct party, and its history since then can roughly be divided into the following periods:

Martemyan Nikitich Ryutin was a Russian Marxist activist, Bolshevik revolutionary, and a political functionary of the Russian Communist Party. Ryutin is best remembered as the leader of a pro-peasant political faction organized against Soviet leader Joseph Stalin in the early 1930s and as the primary author of a 200-page oppositional platform. Ryutin was arrested by the Soviet secret police, along with his co-thinkers, in what has come to be known as the Ryutin Affair. He was executed in January 1937 as part of the "Yezhovshchina" conducted against political oppositionists and suspected economic "wreckers" and spies.

The 17th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) was held during 26 January – 10 February 1934. The congress was attended by 1,225 delegates with a casting vote and 736 delegates with a consultative vote, representing 1,872,488 party members and 935,298 candidate members.

The 15th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) was held during 2–19 December 1927 in Moscow. It was attended by 898 delegates with a casting vote and 771 with a consultative vote.

The ideology of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) was Marxism–Leninism, an ideology of a centralised command economy with a vanguardist one-party state to realise the dictatorship of the proletariat. The Soviet Union's ideological commitment to achieving communism included the development of socialism in one country and peaceful coexistence with capitalist countries while engaging in anti-imperialism to defend the international proletariat, combat capitalism and promote the goals of communism. The state ideology of the Soviet Union—and thus Marxism–Leninism—derived and developed from the theories, policies and political praxis of Lenin and Stalin.

The electoral system of the Soviet Union was varying over time, being based upon Chapter XIII of the provisional Fundamental Law of 1922, articles 9 and 10 of the 1924 Constitution and Chapter XI of the 1936 Constitution, with the electoral laws enacted in conformity with those. The Constitution and laws applied to elections in all Soviets, from the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union, the Union republics and autonomous republics, through to regions, districts and towns. Voting was claimed to be secret and direct with universal suffrage. However, in practice, until 1989 voters could vote against candidates preselected by the Communist Party only by spoiling their ballots, whereas votes for the party candidates could be cast simply by submitting a blank ballot.

Georgy Maximilianovich Malenkov was a Soviet politician who briefly succeeded Joseph Stalin as the leader of the Soviet Union. However, at the insistence of the rest of the Presidium, he relinquished control over the party apparatus in exchange for remaining Premier and first among equals within the Soviet collective leadership. He then became embroiled in a power struggle with Nikita Khrushchev that culminated in his removal from the premiership in 1955 as well as the Presidium in 1957.

The Political Bureau of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union was the highest policy-making authority within the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. It was founded in October 1917, and refounded in March 1919, at the 8th Congress of the Bolshevik Party. It was known as the Presidium from 1952 to 1966. The existence of the Politburo ended in 1991 upon the breakup of the Soviet Union.

The Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union was the executive leadership of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, acting between sessions of Congress. According to party statutes, the committee directed all party and governmental activities. Its members were elected by the Party Congress.

References

- ↑ H.N. Brailsford, A Soviet Election Archived 2017-03-22 at the Wayback Machine , "How the Soviets Work," Vanguard Press, November 1927 (from the Vanguard Studies of Soviet Russia), NY; Marxist Internet Archive.

- ↑ Daniel Thorniley and Kevin Gardiner, Rise And Fall Of The Soviet Rural Communist Party 1927-39, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 1988, p. 32-33.

- ↑ Benjamin Pinkus, The Jews of the Soviet Union: The History of a National Minority, New York: Cambridge University Press, 1988, p. 82.

- ↑ Junius B. Wood, "Soviet Russia's Fourth General Election Quiet: Voting Progresses Without Political Speeches or Campaign Issues," The Cornell Daily Sun, February 10, 1927.

- ↑ Vladimir N. Brovkin, Russia After Lenin: Politics, Culture and Society, 1921-1929, New York: Routledge, 1988, p. 130-131, 165-166, 183-184.

- ↑ Loren R. Graham, The Soviet Academy of Sciences and the Communist Party, 1927-1932, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1967, p. 89-91, 92, 95.

- ↑ Tracy McDonald, Face to the Village: The Riazan Countryside under Soviet Rule, 1921-1930, Buffalo: University of Toronto Press, 2011, p. 111.

- ↑ Hugh D. Hudson Jr., Peasants, Political Police, and the Early Soviet State: Surveillance and Accommodation Under the New Economic Policy, New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2012, p. 59.

- ↑ O. Velikanova, Popular Perceptions of Soviet Politics in the 1920s: Disenchantment of the Dreamers, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013, p. 99.

- ↑ Glennys Young, Power and the Sacred in Revolutionary Russia: Religious Activists in the Village, University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1997, p. 143-144, 188-189, 227, 255, 258-259.

- ↑ Golfo Alexopoulos, Stalin's Outcasts: Aliens, Citizens, and the Soviet State, 1926-1936, London: Cornell University Press, 2003, p. 18, 20, 22-23, 87, 161.