In seismology, an earthquake swarm is a sequence of seismic events occurring in a local area within a relatively short period of time. The length of time used to define a swarm varies, but may be days, months, or years. Such an energy release is different from the situation when a major earthquake is followed by a series of aftershocks: in earthquake swarms, no single earthquake in the sequence is obviously the main shock. In particular, a cluster of aftershocks occurring after a mainshock is not a swarm.

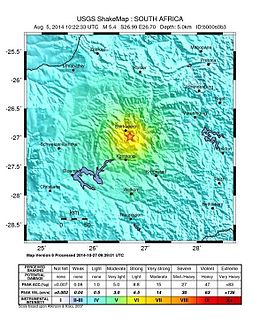

Orkney is a gold mining town situated in the Klerksdorp district of the North West province, South Africa. It lies on the banks of the Vaal River approximately 180 km from Johannesburg near the N12.

The 1989 Newcastle earthquake was an intraplate earthquake that occurred in Newcastle, New South Wales on Thursday 28 December. The shock measured 5.6 on the Richter magnitude scale and was one of Australia's most serious natural disasters, killing 13 people and injuring more than 160. The damage bill has been estimated at A$4 billion, including an insured loss of about $1 billion.

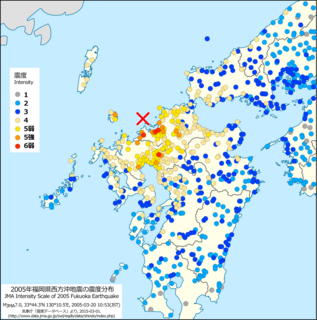

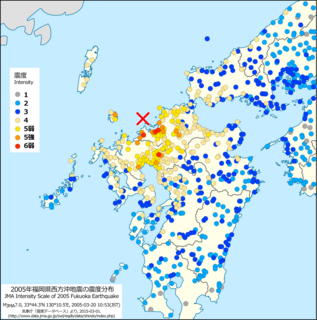

The Fukuoka earthquake struck Fukuoka Prefecture, Japan at 10:53 am JST on March 20, 2005, and lasted for approximately 1 minute. The Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) measured it as peaking at a magnitude of 7.0, whereas the United States Geological Survey (USGS) reported a magnitude of 6.6. The quake occurred along a previously unknown fault in the Genkai Sea, North of Fukuoka city, and the residents of Genkai Island were forced to evacuate as houses collapsed and landslides occurred in places. Investigations subsequent to the earthquake determined that the new fault was most likely an extension of the known Kego fault that runs through the centre of the city.

The 1886 Charleston earthquake occurred about 9:50 p.m. local time August 31. It caused 60 deaths and $5–6 million in damage to 2,000 buildings in the Southeastern United States. It is one of the most powerful and damaging earthquakes to hit the East Coast of the United States.

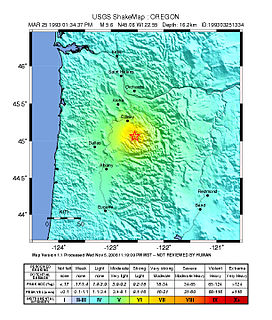

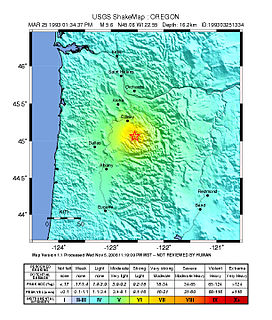

The 1993 Scotts Mills earthquake, also known as the "Spring break quake", occurred in the U.S. state of Oregon on March 25 at 5:34 AM Pacific Standard Time. With a moment magnitude of 5.6 and a maximum perceived intensity of VII on the Mercalli intensity scale, it was the largest earthquake in the Pacific Northwest since the Elk Lake and Goat Rocks earthquakes of 1981. Ground motion was widely felt in Oregon's Willamette Valley, the Portland metropolitan area, and as far north as the Puget Sound area near Seattle, Washington.

The 2008 Illinois earthquake was one of the largest earthquakes ever recorded in the Midwest state of Illinois. This moderate strike-slip shock measured 5.2 on the moment magnitude scale and had a maximum Mercalli intensity of VII (Very strong). It occurred at on April 18 near West Salem and Mount Carmel, Illinois, within the Wabash Valley Seismic Zone. Earthquakes in this part of the country are often felt at great distances.

The 1983 Coalinga earthquake struck at 4:42 p.m. Monday, May 2 of that year, in Coalinga, California.

The 2008 Chino Hills earthquake occurred at 11:42:15 am PDT on July 29 in Southern California. The epicenter of the magnitude 5.4 earthquake was in Chino Hills, c. 28 miles (45 km) east-southeast of downtown Los Angeles. Though no lives were lost, eight people were injured, and it caused considerable damage in numerous structures throughout the area and caused some amusement park facilities to shut down their rides. The earthquake led to increased discussion regarding the possibility of a stronger earthquake in the future.

The 2010 Baja California earthquake occurred on April 4 with a moment magnitude of 7.2 and a maximum Mercalli intensity of VII. The shock originated at south of Guadalupe Victoria, Baja California, Mexico.

The 2010 Pichilemu earthquakes, also known as the Libertador O'Higgins earthquakes, were a pair of intraplate earthquakes measuring 6.9 and 7.0 that struck Chile's O'Higgins Region on 11 March 2010 about 16 minutes apart. The earthquakes were centred 15 kilometres (9.3 mi) northwest of the city of Pichilemu.

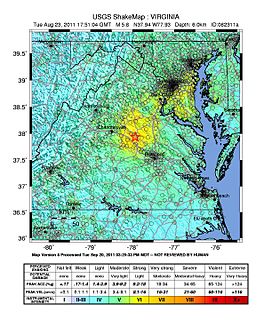

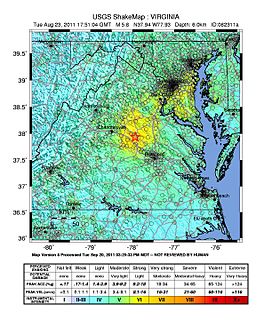

On August 23, 2011, a magnitude 5.8 earthquake hit the Piedmont region of the U.S. state of Virginia at 1:51:04 p.m. EDT. The epicenter, in Louisa County, was 38 mi (61 km) northwest of Richmond and 5 mi (8 km) south-southwest of the town of Mineral. It was an intraplate earthquake with a maximum perceived intensity of VIII (Severe) on the Mercalli intensity scale. Several aftershocks, ranging up to 4.5 in magnitude, occurred after the main tremor.

The 2011 Oklahoma earthquake was a 5.7 magnitude intraplate earthquake which occurred near Prague, Oklahoma on November 5 at 10:53 p.m. CDT in the U.S. state of Oklahoma. The epicenter of the earthquake was in the vicinity of several active wastewater injection wells. According to the United States Geological Survey (USGS), it was the most powerful earthquake ever recorded in Oklahoma; this record was surpassed by the 2016 Oklahoma earthquake. The previous record was a 5.5 magnitude earthquake that struck near the town of El Reno in 1952. The quake's epicenter was approximately 44 miles (71 km) east-northeast of Oklahoma City, near the town of Sparks and was felt in the neighboring states of Texas, Arkansas, Kansas and Missouri and even as far away as Tennessee and Wisconsin. The quake followed several minor quakes earlier in the day, including a 4.7 magnitude foreshock. The quake had a maximum perceived intensity of VIII (Severe) on the Mercalli intensity scale in the area closest to the epicenter. Numerous aftershocks were detected after the main quake, with a few registering at 4.0 magnitude.

The 1993 Klamath Falls earthquakes took place in Klamath Falls, Oregon, beginning on Monday, 20 September at 8:28 p.m. The doublet earthquake registered respective magnitudes of 6.0 and 5.9 on the moment magnitude scale. The earthquakes were located at a depth of 5.6 miles (9 km) and tremors continued to be felt more than three months after the initial shocks.

The 1965 Valparaíso earthquake struck near the city of La Ligua in the Valparaíso Region, Chile, about 140 kilometers from the capital Santiago on Sunday, March 28 at 12:33 p.m. (UTC−03:00). The moment magnitude Mw 7.4–7.6 temblor killed an approximate 500 people and caused damages amounting to some US$1 billion. Many of the deaths were from El Cobre, a mining location that was wiped out after a series of dam failures caused by the earthquake spilled mineral waste onto the area, burying hundreds of residents. The shock was so powerful that it could be felt throughout the country and even across the continent to the Atlantic coast of Argentina.

The 1990 Carlentini earthquake occurred off the Sicilian coast, 20 km east northeast from the town of Augusta, Sicily on 13 December at 01:24 local time. The moderately-sized earthquake measuring 5.6 on the moment magnitude scale (Mw ) resulted in the deaths of 19 people and caused at least 200 injuries. It also inflicted significant damage in the region, leaving 2,500 homeless.

An earthquake struck approximately 53 kilometres SSE of the town of Mansfield, in the Victorian Alps of Australia on 22 September 2021, at 09:15 local time. The earthquake measured 5.9 on the moment magnitude scale. The earthquake caused minor structural damage in parts of Melbourne and left one person injured. The earthquake was also felt in New South Wales, Australian Capital Territory, South Australia and Tasmania. The earthquake was substantially stronger than the 1989 Newcastle earthquake that measured 5.6 and killed 13 people.

The 2021 Lasithi earthquake was a magnitude 6.4 earthquake with a maximum intensity of VIII (Severe) on the Modified Mercalli Intensity Scale which occurred on October 12, 2021, 12:24 (UTC+3:30) off the island of Crete. The quake was also felt at low intensity as far as Cairo and Istanbul.