Maximilian, Margrave of Baden, also known as Max von Baden, was a German prince, general, and politician. He was heir presumptive to the throne of the Grand Duchy of Baden, and in October and November 1918 briefly served as the last chancellor of the German Empire and minister-president of Prussia. He sued for peace on Germany's behalf at the end of World War I based on U.S. President Woodrow Wilson's Fourteen Points, which included immediately transforming the government into a parliamentary system, by handing over the office of chancellor to SPD Chairman Friedrich Ebert and unilaterally proclaiming the abdication of Emperor Wilhelm II. Both events took place on 9 November 1918, the beginning of the Weimar Republic.

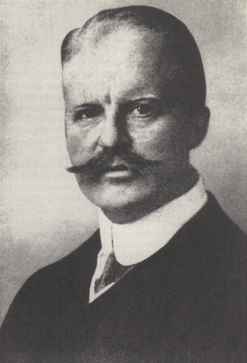

Theobald Theodor Friedrich Alfred von Bethmann Hollweg was a German politician who was Chancellor of the German Empire from 1909 to 1917. He oversaw the German entry into World War I and played a key role during its first three years. He was replaced as chancellor in July of 1917 due in large part to opposition to his moderate policies by leaders in the military.

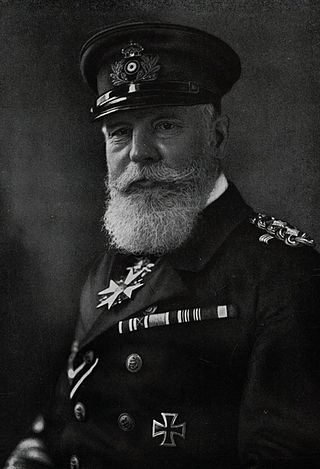

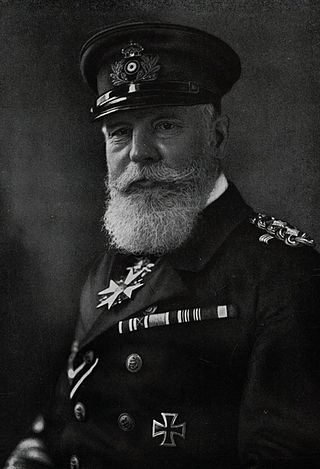

Alfred Peter Friedrich von Tirpitz was a German grand admiral, Secretary of State of the German Imperial Naval Office, the powerful administrative branch of the German Imperial Navy from 1897 until 1916. Prussia never had a major navy, nor did the other German states before the German Empire was formed in 1871. Tirpitz took the modest Imperial Navy and, starting in the 1890s, turned it into a world-class force that could threaten Britain's Royal Navy. However, during World War I, his High Seas Fleet proved unable to end Britain's command of the sea and its chokehold on Germany's economy. The one great engagement at sea, the Battle of Jutland, ended in a narrow German tactical victory but a strategic failure. As the High Seas Fleet's limitations became increasingly apparent during the war, Tirpitz became an outspoken advocate for unrestricted submarine warfare, a policy which would ultimately bring Germany into conflict with the United States. By the beginning of 1916, he was dismissed from office and never regained power.

Carl Friedrich Heinrich Reinhard Scheer was an Admiral in the Imperial German Navy. Scheer joined the navy in 1879 as an officer cadet and progressed through the ranks, commanding cruisers and battleships, as well as senior staff positions on land. At the outbreak of World War I, Scheer was the commander of the II Battle Squadron of the High Seas Fleet. He then took command of the III Battle Squadron, which consisted of the newest and most powerful battleships in the navy. In January 1916, he was promoted to Admiral and given control of the High Seas Fleet. Scheer led the German fleet at the Battle of Jutland on 31 May – 1 June 1916, one of the largest naval battles in history.

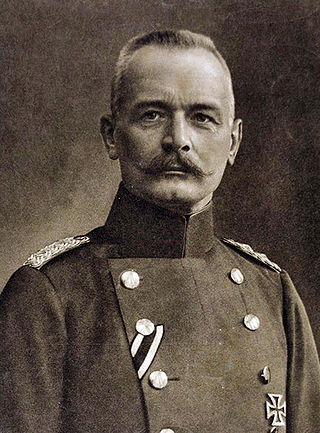

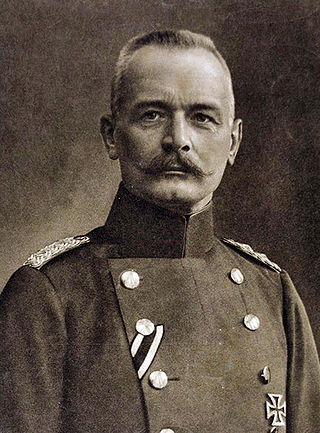

General Erich Georg Sebastian Anton von Falkenhayn was the second Chief of the German General Staff of the First World War from September 1914 until 29 August 1916. He was removed on 29 August 1916 after the failure at the Battle of Verdun, the opening of the Battle of the Somme, the Brusilov Offensive and the entry of Romania into the war on the Allied side undid his strategy to end the war before 1917. He was later given important field commands in Romania and Syria. His reputation as a war leader was attacked in Germany during and after the war, especially by the faction supporting Paul von Hindenburg. Falkenhayn held that Germany could not win the war by a decisive battle but would have to reach a compromise peace; his enemies said he lacked the resolve necessary to win a decisive victory. Falkenhayn's relations with the Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg were troubled and undercut Falkenhayn's plans.

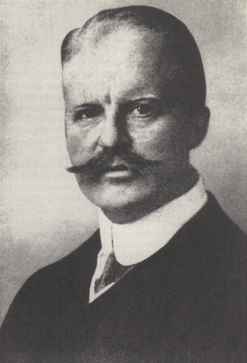

Arthur Zimmermann was State Secretary for Foreign Affairs of the German Empire from 22 November 1916 until his resignation on 6 August 1917. His name is associated with the Zimmermann Telegram during World War I. He was also closely involved in plans to support rebellions in Ireland and in India, and to assist the Bolsheviks to undermine Tsarist Russia.

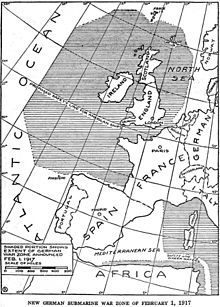

Unrestricted submarine warfare is a type of naval warfare in which submarines sink merchant ships such as freighters and tankers without warning, as opposed to attacks per prize rules that call for warships to search merchantmen and place crews in "a place of safety" before sinking them, unless the ship shows "persistent refusal to stop ... or active resistance to visit or search". To follow the rules a submarine must surface, defeating the purpose of submarines and putting itself in danger of attack.

Henning Rudolf Adolf Karl von Holtzendorff was a German admiral during World War I, who became famous for his December 1916 memo about unrestricted submarine warfare against the United Kingdom. He was a recipient of Order of the Black Eagle and the Pour le Mérite with oak leaves and was one of just six Grand Admirals of the Imperial German Navy.

Hugo von Pohl was a German admiral who served during the First World War. He joined the Navy in 1872 and served in various capacities, including with the new torpedo boats in the 1880s, and in the Reichsmarineamt in the 1890s. He eventually reached the rank of Vizeadmiral and held the position of Chief of the Admiralty Staff in 1913. He commanded the German High Seas Fleet from February 1915 until January 1916. As the commander of the surface fleet, he was exceedingly cautious, and did not engage the High Seas Fleet in any actions with the British Grand Fleet. Pohl was an outspoken advocate of unrestricted submarine warfare, and he put the policy into effect once he took command of the fleet on 4 February 1915. Seriously ill from liver cancer by January 1916, Pohl was replaced by Reinhard Scheer that month. Pohl died a month later.

Admiral Eduard von Capelle was a German Imperial Navy officer from Celle. He served in the navy from 1872 until his retirement in October, 1918. During his career, Capelle served in the Reichsmarineamt, where he was primarily responsible for writing the Fleet Laws that funded the expansion of the High Seas Fleet. By the time he retired, Capelle had risen to the rank of admiral, and had served at the post of state secretary for the Reichsmarineamt. From this post, he oversaw the German naval war during the latter three years of World War I. Capelle retired to Wiesbaden, where he died on 23 February 1931.

The Oberste Heeresleitung was the highest echelon of command of the army (Heer) of the German Empire. In the latter part of World War I, the Third OHL assumed dictatorial powers and became the de facto political authority in the empire.

The July Crisis was a series of interrelated diplomatic and military escalations among the major powers of Europe in the summer of 1914, which led to the outbreak of World War I. The crisis began on 28 June 1914, when Gavrilo Princip, a Bosnian Serb nationalist, assassinated Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir presumptive to the Austro-Hungarian throne, and his wife Sophie, Duchess of Hohenberg. A complex web of alliances, coupled with the miscalculations of many political and military leaders, resulted in an outbreak of hostilities among most major European nations by early August 1914.

Colonel Max Hermann Bauer was a German General Staff officer and artillery expert in the First World War. As a protege of Erich Ludendorff he was placed in charge of the German Army's munition supply by the latter in 1916. In this role he played a leading role in the Hindenburg Programme and the High Command's political machinations. Later Bauer was a military and industrial adviser to the Republic of China under Chiang Kai-shek.

During World War I, the German Empire was one of the Central Powers. It began participation in the conflict after the declaration of war against Serbia by its ally, Austria-Hungary. German forces fought the Allies on both the eastern and western fronts, although German territory itself remained relatively safe from widespread invasion for most of the war, except for a brief period in 1914 when East Prussia was invaded. A tight blockade imposed by the Royal Navy caused severe food shortages in the cities, especially in the winter of 1916–17, known as the Turnip Winter. At the end of the war, Germany's defeat and widespread popular discontent triggered the German Revolution of 1918–1919 which overthrew the monarchy and established the Weimar Republic.

SS Arabic was a British-registered ocean liner that entered service in 1903 for the White Star Line. She was sunk on 19 August 1915, during the First World War, by German submarine SM U-24, 50 mi (80 km) south of Kinsale, causing a diplomatic incident.

The U-boat Campaign from 1914 to 1918 was the World War I naval campaign fought by German U-boats against the trade routes of the Allies. It took place largely in the seas around the British Isles and in the Mediterranean. The German Empire relied on imports for food and domestic food production and the United Kingdom relied heavily on imports to feed its population, and both required raw materials to supply their war industry; the powers aimed, therefore, to blockade one another. The British had the Royal Navy which was superior in numbers and could operate on most of the world's oceans because of the British Empire, whereas the Imperial German Navy surface fleet was mainly restricted to the German Bight, and used commerce raiders and unrestricted submarine warfare to operate elsewhere.

The Pless conference was a conference held at the castle of Prince Pless located in the Duchy of Pless on January 8, 1917. The conference involved the German army and navy arguing which division should take command of German activity in World War I. The German navy under Admiral Holtzendorff desired unrestricted submarine warfare to shut down the North Atlantic trade supplying Britain with food and munitions. The navy felt that it could starve Britain within six months to a year, before American troops could arrive on the Western Front and change the war. A memo was drafted by Admiral Holtzendorff in December 1916 before the Pless Conference, that argued for unrestricted submarine warfare. Pressure mounted on Kaiser Wilhem II to agree with the memo, which he had previously disagreed with due to his commitment to a policy of moderation.

The German Imperial War Council of 8 December 1912 was an informal conference of some of the highest military leaders of the German Empire. Meeting at the Stadtschloss in Berlin, they discussed and debated the tense military and diplomatic situation in Europe at the time. As a result of the Russian Great Military Program announced in November, Austria-Hungary's concerns about Serbian successes in the First Balkan War, and certain British communications, the possibility of war was a prime topic of the meeting.

Georg Alexander von Müller was an Admiral of the Imperial German Navy and a close friend of the Kaiser in the run up to the First World War.

The Friedrich-August Cross was a German decoration of the First World War. It was set up on 24 September 1914 by Frederick Augustus II, Grand Duke of Oldenburg, with two classes, for "all persons of military or civilian status, who have shown outstanding service during the war itself".