Pocahontas was a Native American woman belonging to the Powhatan people, notable for her association with the colonial settlement at Jamestown, Virginia. She was the daughter of Powhatan, the paramount chief of a network of tributary tribes in the Tsenacommacah, encompassing the Tidewater region of what is today the U.S. state of Virginia.

The Powhatan people (;) are Native Americans who belong to member tribes of the Powhatan Confederacy, or Tsenacommacah. They are Algonquian peoples whose historic territories were in eastern Virginia.

Opechancanough was paramount chief of the Powhatan Confederacy in present-day Virginia from 1618 until his death. He had been a leader in the confederacy formed by his older brother Powhatan, from whom he inherited the paramountcy.

Powhatan, whose proper name was Wahunsenacawh, was the leader of the Powhatan, an alliance of Algonquian-speaking Native Americans living in Tsenacommacah, in the Tidewater region of Virginia at the time when English settlers landed at Jamestown in 1607.

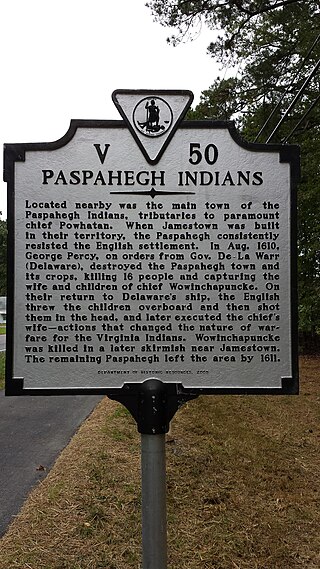

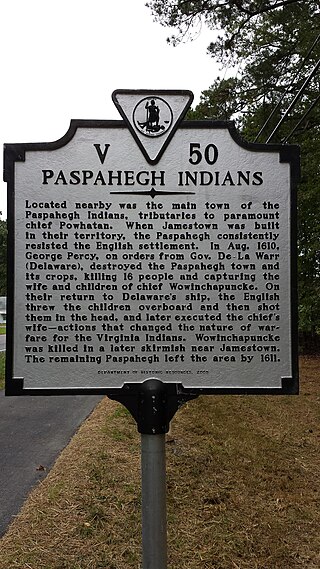

The Paspahegh tribe was a Native American tributary to the Powhatan paramount chiefdom, incorporated into the chiefdom around 1596 or 1597. The Paspahegh Indian tribe lived in present-day Charles City and James City counties, Virginia. The Powhatan Confederacy included Indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands who spoke a related Eastern Algonquian languages.

The Indian massacre of 1622 took place in the English colony of Virginia on 1 April [O.S. 22 March] 1622. English explorer John Smith, though he was not an eyewitness, wrote in his History of Virginia that warriors of the Powhatan "came unarmed into our houses with deer, turkeys, fish, fruits, and other provisions to sell us"; they then grabbed any tools or weapons available and killed all English settlers they found, including men, women, and children of all ages. Opechancanough, chief of the Powhatan Confederacy, led a coordinated series of surprise attacks that ended up killing a total of 347 people — a quarter of the population of the Colony of Virginia.

The Pamunkey Indian Tribe is one of 11 Virginia Indian tribal governments recognized by the Commonwealth of Virginia, and the state's first federally recognized tribe, receiving its status in January 2016. Six other Virginia tribal governments, the Chickahominy, the Eastern Chickahominy, the Upper Mattaponi, the Rappahannock, the Monacan, and the Nansemond, were similarly recognized through the passage of the Thomasina E. Jordan Indian Tribes of Virginia Federal Recognition Act of 2017 on January 12, 2018. The historical people were part of the Powhatan paramountcy, made up of Algonquian-speaking nations. The Powhatan paramount chiefdom was made up of over 30 nations, estimated to total about 10,000–15,000 people at the time the English arrived in 1607. The Pamunkey nation made up about one-tenth to one-fifteenth of the total, as they numbered about 1,000 persons in 1607.

The Machapunga were a small Algonquian language–speaking Native American tribe from coastal northeastern North Carolina. They were part of the Secotan people. They were a group from the Powhatan Confederacy who migrated from present-day Virginia.

Turkey Tayac, legally Philip Sheridan Proctor (1895–1978), was a Piscataway leader and herbal medicine practitioner; he was notable in Native American activism for tribal and cultural revival in the 20th century. He had some knowledge of the Piscataway language and was consulted by the Algonquian linguist, Ives Goddard, as well as Julian Granberry.

The Native American tribes in Virginia are the Indigenous peoples whose tribal nations historically or currently are based in the Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States of America.

The Piscataway or Piscatawa, are Native Americans. They spoke Algonquian Piscataway, a dialect of Nanticoke. One of their neighboring tribes, with whom they merged after a massive decline of population following two centuries of interactions with European settlers, called them the Conoy.

Tsenacommacah is the name given by the Powhatan people to their native homeland, the area encompassing all of Tidewater Virginia and parts of the Eastern Shore. More precisely, its boundaries spanned 100 miles (160 km) by 100 miles (160 km) from near the south side of the mouth of the James River all the way north to the south end of the Potomac River and from the Eastern Shore west to about the Fall Line of the rivers.

The Anglo–Powhatan Wars were three wars fought between settlers of the Colony of Virginia and the Powhatan People of Tsenacommacah in the early 17th century. The first war started in 1609 and ended in a peace settlement in 1614. The second war lasted from 1622 to 1632. The third war lasted from 1644 until 1646 and ended when Opechancanough was captured and killed. That war resulted in a defined boundary between the Indians and colonial lands that could only be crossed for official business with a special pass. This situation lasted until 1677 and the Treaty of Middle Plantation which established Indian reservations following Bacon's Rebellion.

The Chesepian or Chesapeake were a Native American tribe who lived near present-day South Hampton Roads in the U.S. state of Virginia. They occupied an area which is now the Norfolk County or Princess Anne County.

The Nottoway are an Iroquoian Native American tribe in Virginia. The Nottoway spoke a Nottoway language in the Iroquoian language family.

The Doeg were a Native American people who lived in Virginia. They spoke an Algonquian language and may have been a branch of the Nanticoke tribe, historically based on the Eastern Shore of Maryland. The Nanticoke considered the Algonquian Lenape as "grandfathers". The Doeg are known for a raid in July 1675 that contributed to colonists' uprising in Bacon's Rebellion.

The Pocomoke people were a historic Native American tribe whose territory encompassed the rivers Pocomoke, Great Annemessex, Little Annemessex, and Manokin, the bays of Monie and Chincoteague, and the sounds of Pocomoke and Tangier.

The Weyanoke people were an Indigenous people of the Northeastern Woodlands.

The Accohannock Indian Tribe, Inc. is a state-recognized tribe in Maryland and a nonprofit organization of individuals who identify as descendants of the Accohannock people.

The Annamessex people were a historic Native American tribe from the Eastern Shore of Maryland. Their homelands were part of present-day Somerset County, Maryland.