Related Research Articles

Sir Peter Karel, Baron Piot, is a Belgian-British microbiologist known for his research into Ebola and AIDS.

Partners In Health (PIH) is an international nonprofit public health organization founded in 1987 by Paul Farmer, Ophelia Dahl, Thomas J. White, Todd McCormack, and Jim Yong Kim.

Yoshihiro Kawaoka is a virologist specializing in the study of the influenza and Ebola viruses. He holds a professorship in virology in the Department of Pathobiological Sciences at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, USA, and at the University of Tokyo, Japan.

In terms of available healthcare and health status Sierra Leone is rated very poorly. Globally, infant and maternal mortality rates remain among the highest. The major causes of illness within the country are preventable with modern technology and medical advances. Most deaths within the country are attributed to nutritional deficiencies, lack of access to clean water, pneumonia, diarrheal diseases, anemia, malaria, tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS.

The central chimpanzee or the tschego is a subspecies of chimpanzee closely related to the other great apes such as gorillas, orangutans, and humans. The central chimpanzee can be found in Central Africa, mostly in Gabon, Cameroon, Republic of Congo and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Traditional African medicine is a range of traditional medicine disciplines involving indigenous herbalism and African spirituality, typically including diviners, midwives, and herbalists. Practitioners of traditional African medicine claim, largely without evidence, to be able to cure a variety of diverse conditions including cancer, psychiatric disorders, high blood pressure, cholera, most venereal diseases, epilepsy, asthma, eczema, fever, anxiety, depression, benign prostatic hyperplasia, urinary tract infections, gout, and healing of wounds and burns and even Ebola.

Guinea faces a number of ongoing health challenges.

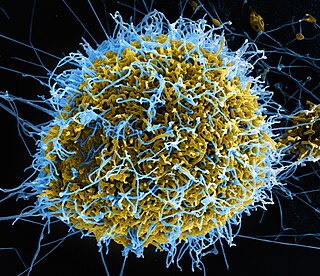

Ebola, also known as Ebola virus disease (EVD) and Ebola hemorrhagic fever (EHF), is a viral hemorrhagic fever in humans and other primates, caused by ebolaviruses. Symptoms typically start anywhere between two days and three weeks after infection. The first symptoms are usually fever, sore throat, muscle pain, and headaches. These are usually followed by vomiting, diarrhoea, rash and decreased liver and kidney function, at which point some people begin to bleed both internally and externally. It kills between 25% and 90% of those infected – about 50% on average. Death is often due to shock from fluid loss, and typically occurs between six and 16 days after the first symptoms appear. Early treatment of symptoms increases the survival rate considerably compared to late start. An Ebola vaccine was approved by the US FDA in December 2019.

The 2013–2016 epidemic of Ebola virus disease, centered in Western Africa, was the most widespread outbreak of the disease in history. It caused major loss of life and socioeconomic disruption in the region, mainly in Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone. The first cases were recorded in Guinea in December 2013; later, the disease spread to neighbouring Liberia and Sierra Leone, with minor outbreaks occurring in Nigeria and Mali. Secondary infections of medical workers occurred in the United States and Spain. In addition, isolated cases were recorded in Senegal, the United Kingdom and Italy. The number of cases peaked in October 2014 and then began to decline gradually, following the commitment of substantial international resources.

An Ebola virus epidemic in Sierra Leone occurred in 2014, along with the neighbouring countries of Guinea and Liberia. At the time it was discovered, it was thought that Ebola virus was not endemic to Sierra Leone or to the West African region and that the epidemic represented the first time the virus was discovered there. However, some samples taken for Lassa fever testing turned out to be Ebola virus disease when re-tested for Ebola in 2014, showing that Ebola had been in Sierra Leone as early as 2006.

Ebola vaccines are vaccines either approved or in development to prevent Ebola. As of 2022, there are only vaccines against the Zaire ebolavirus. The first vaccine to be approved in the United States was rVSV-ZEBOV in December 2019. It had been used extensively in the Kivu Ebola epidemic under a compassionate use protocol. During the early 21st century, several vaccine candidates displayed efficacy to protect nonhuman primates against lethal infection.

Organizations from around the world responded to the West African Ebola virus epidemic. In July 2014, the World Health Organization (WHO) convened an emergency meeting with health ministers from eleven countries and announced collaboration on a strategy to co-ordinate technical support to combat the epidemic. In August, they declared the outbreak an international public health emergency and published a roadmap to guide and coordinate the international response to the outbreak, aiming to stop ongoing Ebola transmission worldwide within 6–9 months. In September, the United Nations Security Council declared the Ebola virus outbreak in the West Africa subregion a "threat to international peace and security" and unanimously adopted a resolution urging UN member states to provide more resources to fight the outbreak; the WHO stated that the cost for combating the epidemic will be a minimum of $1 billion.

There is no cure or specific treatment for the Ebola virus disease that is currently approved for market, although various experimental treatments are being developed. For past and current Ebola epidemics, treatment has been primarily supportive in nature.

Post-Ebola virus syndrome is a post-viral syndrome affecting those who have recovered from infection with Ebola. Symptoms include joint and muscle pain, eye problems, including blindness, various neurological problems, and other ailments, sometimes so severe that the person is unable to work. Although similar symptoms had been reported following previous outbreaks in the last 20 years, health professionals began using the term in 2014 when referring to a constellation of symptoms seen in people who had recovered from an acute attack of Ebola disease.

Melissa Leach, is a British geographer and social anthropologist. She studies sustainability and development concerns in policy-making and has a focus on the politics of science and technology of Africa. As of 2017 she was the Director of the Institute of Development Studies (IDS) located on the University of Sussex campus.

Judith Glynn is a Professor of Epidemiology at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. She worked on the Karonga Prevention Study on HIV and Tuberculosis in Malawi. She is also a sculptor.

Sarah Ssali, is a Ugandan social scientist, researcher, academic and academic administrator, who is an associate professor and dean of the School of Gender Studies at Makerere University, Uganda's oldest and largest public university.

Nahid Bhadelia is an American infectious-diseases physician, founding director of Center for Emerging Infectious Diseases Policy and Research (CEID), an associate director at National Emerging Infectious Diseases Laboratories (NEIDL) at Boston University, and an associate professor at the Boston University School of Medicine. She currently serves as the Senior Policy Advisor for Global COVID-19 Response on the White House COVID-19 Response Team.

Caitlin M. Rivers is an American epidemiologist who as Senior Scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security and assistant professor at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, specializing on improving epidemic preparedness. Rivers is currently working on the American response to the COVID-19 pandemic with a focus on the incorporation of infectious disease modeling and forecasting into public health decision making.

References

- 1 2 "Adia Benton : Department of Anthropology - Northwestern University". anthropology.northwestern.edu. Retrieved March 6, 2021.

- ↑ Sarraf, Isabelle (March 20, 2020). "NU researcher Adia Benton talks COVID-19, "flattening the curve"". The Daily Northwestern. Retrieved February 3, 2022.

- ↑ Zirin, Dave (March 17, 2020). "'We Will Get Our Sports Back When We Deserve To': A Q&A With Dr. Adia Benton". ISSN 0027-8378 . Retrieved February 3, 2022.

- ↑ Benton, Adia. "Adia Benton's CV" (PDF).

- ↑ "Adia Benton | News from Brown". news.brown.edu. Retrieved March 6, 2021.

- ↑ "Adia Benton recent appearances/publications in the news about Ebola | Department of Anthropology". www.brown.edu. Retrieved March 6, 2021.

- ↑ "Adia Benton". Society for Social Studies of Science. Retrieved March 6, 2021.[ permanent dead link ]