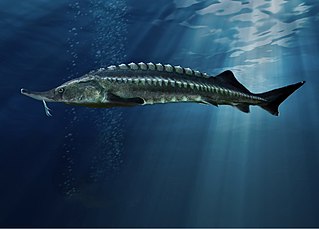

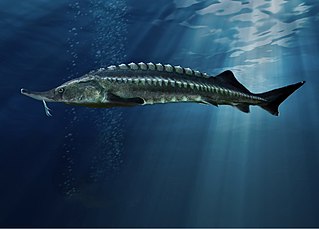

Sturgeon is the common name for the 28 species of fish belonging to the family Acipenseridae. The earliest sturgeon fossils date to the Late Cretaceous, and are descended from other, earlier acipenseriform fish, which date back to the Early Jurassic period, some 174 to 201 million years ago. They are one of two living families of the Acipenseriformes alongside paddlefish (Polyodontidae). The family is grouped into four genera: Acipenser, Huso, Scaphirhynchus, and Pseudoscaphirhynchus. Two species may be extinct in the wild, and one may be entirely extinct. Sturgeons are native to subtropical, temperate and sub-Arctic rivers, lakes and coastlines of Eurasia and North America. A Maastrichtian-age fossil found in Morocco shows that they also once lived in Africa.

The beluga, also known as the beluga sturgeon or great sturgeon, is a species of anadromous fish in the sturgeon family (Acipenseridae) of the order Acipenseriformes. It is found primarily in the Caspian and Black Sea basins, and formerly in the Adriatic Sea. Based on maximum size, it is the third-most-massive living species of bony fish. Heavily fished for the female's valuable roe, known as beluga caviar, wild populations have been greatly reduced by overfishing and poaching, leading IUCN to classify the species as critically endangered.

The kaluga, also known as the river beluga, is a large predatory sturgeon found in the Amur River basin. With a maximum size of at least 1,000 kg (2,205 lb) and 5.6 m (18.6 ft), the kaluga is one of the biggest of the sturgeon family. Like the slightly larger beluga, it spends part of its life in salt water. Unlike the beluga, this fish has 5 major rows of dermal scutes and feeds on salmon and other fish in the Amur. They have gray-green to black backs with a yellowish green-white underbelly.

Acipenser is a genus of sturgeons. With 17 living species, it is the largest genus in the order Acipenseriformes. The genus is paraphyletic, containing all sturgeons that do not belong to Huso, Scaphirhynchus, or Pseudoscaphirhynchus, with many species more closely related to the other three genera than they are to other species of Acipenser. They are native to freshwater and estuarine systems of Eurasia and North America, and most species are threatened. Several species also known to enter near-shore marine environments in the Atlantic, Arctic and Pacific oceans.

The Chinese sturgeon is a critically endangered member of the family Acipenseridae in the order Acipenseriformes. Historically, this anadromous fish was found in China, Japan, and the Korean Peninsula, but it has been extirpated from most regions due to habitat loss and overfishing.

The European sea sturgeon, also known as the Atlantic sturgeon or common sturgeon, is a species of sturgeon native to Europe. It was formerly abundant, being found in coastal habitats all over Europe. Most specifically, they reach the Black and Baltic Sea. It is anadromous and breeds in rivers. It is currently a critically endangered species. Although the name Baltic sturgeon sometimes has been used, it has now been established that sturgeon of the Baltic region are A. oxyrinchus, a species otherwise restricted to the Atlantic coast of North America.

White sturgeon is a species of sturgeon in the family Acipenseridae of the order Acipenseriformes. They are an anadromous (migratory) fish species ranging in the Eastern Pacific; from the Gulf of Alaska to Monterey, California. However, some are landlocked in the Columbia River Drainage, Montana, and Lake Shasta in California, with reported sightings in northern Baja California, Mexico.

The Atlantic sturgeon is a member of the family Acipenseridae, and, along with other sturgeon, it is sometimes considered a living fossil. The Atlantic sturgeon is one of two subspecies of A. oxyrinchus, the other being the Gulf sturgeon. The main range of the Atlantic sturgeon is in eastern North America, extending from New Brunswick, Canada, to the eastern coast of Florida, United States. A disjunct population occurs in the Baltic region of Europe. The Atlantic sturgeon was in great abundance when the first European settlers came to North America, but has since declined due to overfishing, water pollution, and habitat impediments such as dams. It is considered threatened, endangered, and even locally extinct in many of its original habitats. The fish can reach 60 years of age, 15 ft (4.6 m) in length and over 800 lb (360 kg) in weight.

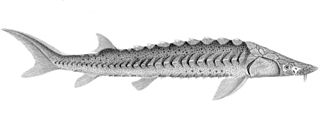

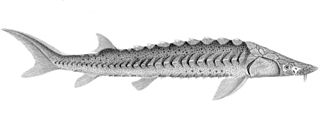

The shovelnose sturgeon is the smallest species of freshwater sturgeon native to North America. It is often called hackleback, sand sturgeon, or switchtail. Switchtail refers to the long filament found on the upper lobe of the caudal fin. Shovelnose sturgeon are the most abundant sturgeon found in the Missouri River and Mississippi River systems, and were formerly a commercially fished sturgeon in the United States of America. In 2010, they were listed as threatened under the U.S. Endangered Species Act due to their resemblance to the endangered pallid sturgeon, with which shovelnose sturgeon are sympatric.

The sterlet is a relatively small species of sturgeon from Eurasia native to large rivers that flow into the Black Sea, Azov Sea, and Caspian Sea, as well as rivers in Siberia as far east as Yenisei. Populations migrating between fresh and salt water (anadromous) have been extirpated. It is also known as the sterlet sturgeon.

The starry sturgeon also known as stellate sturgeon or sevruga, is a species of sturgeon. It is native to the Black, Azov, Caspian and Aegean sea basins, but it has been extirpated from the last and it is predicted that the remaining natural population will follow soon due to overfishing.

The shortnose sturgeon is a small and endangered species of North American sturgeon. The earliest remains of the species are from the Late Cretaceous Period, over 70 million years ago. Shortnose sturgeons are long-lived and slow to sexually mature. Most sturgeons are anadromous bottom-feeders, which means they migrate upstream to spawn but spend most of their lives feeding in rivers, deltas and estuaries. The shortnose sturgeon is often mistaken as a juvenile Atlantic sturgeon because of its small size. Prior to 1973, U.S. commercial fishing records did not differentiate between the two species: both were reported as "common sturgeon", although it is believed based on sizes that the bulk of the catch was Atlantic sturgeon. The shortnose is distinguishable from the Atlantic sturgeon due to its shorter and rounder head.

The green sturgeon is a species of sturgeon native to the northern Pacific Ocean, from China and Russia to Canada and the United States.

The Persian sturgeon is a species of fish in the family Acipenseridae. It is found in the Caspian Sea and to a lesser extent the Black Sea and ascends certain rivers to spawn, mainly the Volga, Kura, Araks and Ural Rivers. It is heavily fished for its flesh and its roe and is limited in its up-river migrations by damming of the rivers. Young fish feed on small invertebrates, graduating to larger prey such as crabs and fish as they grow. The threats faced by this fish include excessive fishing with the removal of immature fish before they have bred, damming of the rivers, loss of spawning areas and water pollution. The International Union for Conservation of Nature has listed the fish as critically endangered and has suggested that the increased provision of hatcheries could be of benefit.

The Siberian sturgeon is a species of sturgeon in the family Acipenseridae. It is most present in all of the major Siberian river basins that drain northward into the Kara, Laptev and East Siberian Seas, including the Ob, Yenisei Lena, and Kolyma Rivers. It is also found in Kazakhstan and China in the Irtysh River, a major tributary of the Ob. The species epithet honors the German Russian biologist Karl Ernst von Baer.

Dabry's sturgeon, also known as the Yangtze sturgeon, Changjiang sturgeon and river sturgeon, is a species of fish in the sturgeon family, Acipenseridae. It is endemic to China and today restricted to the Yangtze River basin, but was also recorded from the Yellow River basin in the past. It was a food fish of commercial importance. Its populations declined drastically, and since 1988, it was designated an endangered species on the Chinese Red List in Category I and commercial harvest was banned. It has been officially declared extinct in the wild by the IUCN as of July 21, 2022.

The Russian sturgeon, also known as the diamond sturgeon or Danube sturgeon, is a species of fish in the family Acipenseridae. It is found in Azerbaijan, Bulgaria, Georgia, Iran, Kazakhstan, Romania, Russia, Turkey, Turkmenistan, and Ukraine. It is also found in the Caspian Sea. This fish can grow up to about 235 cm (93 in) and weigh 115 kg (254 lb). Russian sturgeon mature and reproduce slowly, making them highly vulnerable to fishing. It is distinguished from other Acipenser species by its short snout with a rounded tip as well as its lower lip which is interrupted at its center.

The Sakhalin sturgeon is a species of fish in the family Acipenseridae. It is found in Japan and Russia.

The bastard sturgeon, also known as the fringebarbel sturgeon, ship sturgeon, spiny sturgeon, or thorn sturgeon, is a species of fish in the family Acipenseridae. These fish are typically found along the benthos of shallower waters near shorelines or estuaries.

The Japanese sturgeon or Amur sturgeon is a species of fish in the family Acipenseridae found in the Amur River basin in China and Russia. Claims of its presence in the Sea of Japan need confirmation. The species has 11–16 dorsal, 34–47 lateral, and 7–16 ventral scutes. Their dorsal fins have 38–53 rays and 20–35 anal fin rays. They also have greyish-brown backs and pale ventral sides. The species can reach up to 3 metres (9.8 ft) in length, and weigh over 190 kilograms (420 lb). The species is considered to be critically endangered.