A biosafety level (BSL), or pathogen/protection level, is a set of biocontainment precautions required to isolate dangerous biological agents in an enclosed laboratory facility. The levels of containment range from the lowest biosafety level 1 (BSL-1) to the highest at level 4 (BSL-4). In the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) have specified these levels. In the European Union, the same biosafety levels are defined in a directive. In Canada the four levels are known as Containment Levels. Facilities with these designations are also sometimes given as P1 through P4, as in the term P3 laboratory.

A biological hazard, or biohazard, is a biological substance that poses a threat to the health of living organisms, primarily humans. This could include a sample of a microorganism, virus or toxin that can adversely affect human health. A biohazard could also be a substance harmful to other animals.

Fort Detrick is a United States Army Futures Command installation located in Frederick, Maryland. Fort Detrick was the center of the U.S. biological weapons program from 1943 to 1969. Since the discontinuation of that program, it has hosted most elements of the United States biological defense program.

Viral hemorrhagic fevers (VHFs) are a diverse group of animal and human illnesses in which fever and hemorrhage are caused by a viral infection. VHFs may be caused by five distinct families of RNA viruses: the families Filoviridae, Flaviviridae, Rhabdoviridae, and several member families of the Bunyavirales order such as Arenaviridae, and Hantaviridae. All types of VHF are characterized by fever and bleeding disorders and all can progress to high fever, shock and death in many cases. Some of the VHF agents cause relatively mild illnesses, such as the Scandinavian nephropathia epidemica, while others, such as Ebola virus, can cause severe, life-threatening disease.

The National Microbiology Laboratory (NML) is part of the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC), the agency of the Government of Canada that is responsible for public health, health emergency preparedness and response, and infectious and chronic disease control and prevention.

The Hot Zone: A Terrifying True Story is a best-selling 1994 nonfiction thriller by Richard Preston about the origins and incidents involving viral hemorrhagic fevers, particularly ebolaviruses and marburgviruses. The basis of the book was Preston's 1992 New Yorker article "Crisis in the Hot Zone".

The United States Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases is the U.S Army's main institution and facility for defensive research into countermeasures against biological warfare. It is located on Fort Detrick, Maryland, near Washington, D.C. and is a subordinate lab of the U.S. Army Medical Research and Development Command (USAMRDC), headquartered on the same installation.

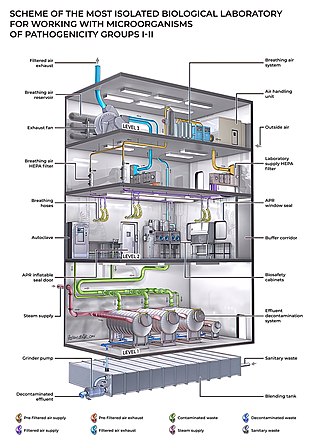

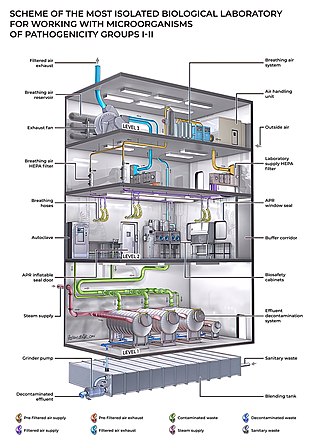

One use of the concept of biocontainment is related to laboratory biosafety and pertains to microbiology laboratories in which the physical containment of pathogenic organisms or agents is required, usually by isolation in environmentally and biologically secure cabinets or rooms, to prevent accidental infection of workers or release into the surrounding community during scientific research.

The Critical Care Air Transport Team (CCATT) concept dates from 1988, when Col. P.K. Carlton and Maj. J. Chris Farmer originated the development of this program while stationed at U.S. Air Force Hospital Scott, Scott Air Force Base, Illinois. Dr. Carlton was the Hospital Commander, and Dr. Farmer was a staff intensivist. The program was developed because of an inability to transport and care for a patient who became critically ill during a trans-Atlantic air evac mission in a C-141. They envisioned a highly portable intensive care unit (ICU) with sophisticated capabilities, carried in backpacks, that would match on-the-ground ICU functionality.

In health care facilities, isolation represents one of several measures that can be taken to implement in infection control: the prevention of communicable diseases from being transmitted from a patient to other patients, health care workers, and visitors, or from outsiders to a particular patient. Various forms of isolation exist, in some of which contact procedures are modified, and others in which the patient is kept away from all other people. In a system devised, and periodically revised, by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), various levels of patient isolation comprise application of one or more formally described "precaution".

Positive pressure personnel suits (PPPS)—or positive pressure protective suits, informally known as "space suits", "moon suits", "blue suits", etc.—are highly specialized, totally encapsulating, industrial protection garments worn only within special biocontainment or maximum containment (BSL-4) laboratory facilities. These facilities research dangerous pathogens which are highly infectious and may have no treatments or vaccines available. These facilities also feature other special equipment and procedures such as airlock entry, quick-drench disinfectant showers, special waste disposal systems, and shower exits.

The United States biological defense program—in recent years also called the National Biodefense Strategy—refers to the collective effort by all levels of government, along with private enterprise and other stakeholders, in the United States to carry out biodefense activities.

Ebola, also known as Ebola virus disease (EVD) and Ebola hemorrhagic fever (EHF), is a viral hemorrhagic fever in humans and other primates, caused by ebolaviruses. Symptoms typically start anywhere between two days and three weeks after becoming infected with the virus. The first symptoms are usually fever, sore throat, muscle pain, and headaches. These are usually followed by vomiting, diarrhoea, rash and decreased liver and kidney function, at which point, some people begin to bleed both internally and externally. The disease kills between 25% and 90% of those infected – about 50% on average. Death is often due to shock from fluid loss, and typically occurs between six and 16 days after the first symptoms appear. Early treatment of symptoms increases the survival rate considerably compared to late start.

Four laboratory-confirmed cases of Ebola virus disease occurred in the United States in 2014. Eleven cases were reported, including these four cases and seven cases medically evacuated from other countries. The first was reported in September 2014. Nine of the people contracted the disease outside the US and traveled into the country, either as regular airline passengers or as medical evacuees; of those nine, two died. Two people contracted Ebola in the United States. Both were nurses who treated an Ebola patient; both recovered.

Organizations from around the world responded to the West African Ebola virus epidemic. In July 2014, the World Health Organization (WHO) convened an emergency meeting with health ministers from eleven countries and announced collaboration on a strategy to co-ordinate technical support to combat the epidemic. In August, they declared the outbreak an international public health emergency and published a roadmap to guide and coordinate the international response to the outbreak, aiming to stop ongoing Ebola transmission worldwide within 6–9 months. In September, the United Nations Security Council declared the Ebola virus outbreak in the West Africa subregion a "threat to international peace and security" and unanimously adopted a resolution urging UN member states to provide more resources to fight the outbreak; the WHO stated that the cost for combating the epidemic will be a minimum of $1 billion.

The Aeromedical Biological Containment System (ABCS) is an aeromedical evacuation capability devised by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in collaboration with the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) and government contractor Phoenix Air between 2007 and 2010. Its purpose is to safely air-transport a highly contagious patient; it comprises a transit isolator and an appropriately configured supporting aircraft. Originally developed to support CDC staff who might become infected while investigating avian flu and SARS in East Asia, it was never used until the 2014 Ebola virus epidemic in West Africa, transporting 36 Ebola patients out of West Africa.

A Racal suit is a protective suit with a powered air-purifying respirator (PAPR). It consists of a plastic suit and a battery-operated blower with HEPA filters that supplies filtered air to a positive-pressure hood. Racal suits were among the protective suits used by the Aeromedical Isolation Team (AIT) of the United States Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases to evacuate patients with highly infectious diseases for treatment.

An isolation pod is a capsule which is used to provide medical isolation for a patient. Examples include the Norwegian EpiShuttle and the USAF's Transport Isolation System (TIS) or Portable Bio-Containment Module (PBCM), which are used to provide isolation when transporting patients by air.

In August–November 1976, an outbreak of Ebola virus disease occurred in Zaire. The first recorded case was from Yambuku, a small village in Mongala District, 1,098 kilometres (682 mi) northeast of the capital city of Kinshasa.

John J. Lowe is an American infectious disease scientist, assistant vice chancellor for health security at University of Nebraska Medical Center, and associate professor in the Department of Environmental, Agricultural and Occupational Health at University of Nebraska Medical Center College of Public Health. In 2014, he led Nebraska Medicine hospital’s effort to treat and care for Ebola virus disease patients and led the University of Nebraska Medical Center’s coronavirus disease 2019 response efforts.