Persian literature comprises oral compositions and written texts in the Persian language and is one of the world's oldest literatures. It spans over two-and-a-half millennia. Its sources have been within Greater Iran including present-day Iran, Iraq, Afghanistan, the Caucasus, and Turkey, regions of Central Asia, South Asia and the Balkans where the Persian language has historically been either the native or official language. For example, Rumi, one of the best-loved Persian poets, born in Balkh or Wakhsh, wrote in Persian and lived in Konya, at that time the capital of the Seljuks in Anatolia. The Ghaznavids conquered large territories in Central and South Asia and adopted Persian as their court language. There is thus Persian literature from Iran, Mesopotamia, Azerbaijan, the wider Caucasus, Turkey, Pakistan, Bangladesh, India, Tajikistan and other parts of Central Asia, as well as the Balkans. Not all Persian literature is written in Persian, as some consider works written by ethnic Persians or Iranians in other languages, such as Greek and Arabic, to be included. At the same time, not all literature written in Persian is written by ethnic Persians or Iranians, as Turkic, Caucasian, Indic and Slavic poets and writers have also used the Persian language in the environment of Persianate cultures.

Sohrab Sepehri was a notable Iranian poet and painter. He is considered to be one of the five most famous Iranian poets who have practiced modern poetry alongside Nima Youshij, Ahmad Shamlou, Mehdi Akhavan-Sales, and Forough Farrokhzad. Sepehri's poems have been translated into several languages, including English, French, Spanish, Italian and Lithuanian, Kurdish.

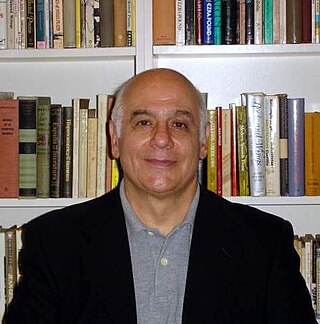

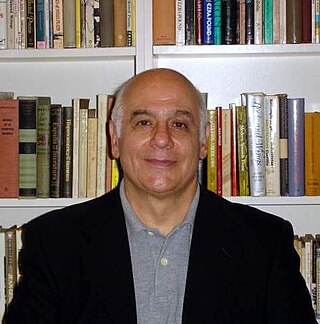

Abdolkarim Soroush, born Hossein Haj Faraj Dabbagh, is an Iranian Islamic thinker, reformer, Rumi scholar, public intellectual, and a former professor of philosophy at the University of Tehran and Imam Khomeini International University. He is arguably the most influential figure in the religious intellectual movement of Iran. Soroush is currently a visiting scholar at the University of Maryland in College Park, Maryland. He was also affiliated with other institutions, including Harvard, Princeton, Yale, Columbia, the Leiden-based International Institute as a visiting professor for the Study of Islam in the Modern World (ISIM) and the Wissenschaftskolleg in Berlin. He was named by Time magazine as one of the world's 100 most influential people in 2005, and by Prospect magazine as one of the most influential intellectuals in the world in 2008. Soroush's ideas, founded on relativism, prompted both supporters and critics to compare his role in reforming Islam to that of Martin Luther in reforming Christianity.

Simin Behbahani, her surname also appears as Bihbahani was a prominent Iranian contemporary poet, lyricist and activist. She is known for her poems in a ghazal-style of poetic form. She was an icon of modern Persian poetry, Iranian intelligentsia and literati who affectionately refer to her as the lioness of Iran. She was nominated twice for the Nobel Prize in literature, and "received many literary accolades around the world."

Nader Naderpour was an Iranian poet.

Jaafar Modarres-Sadeghi is an Iranian novelist and editor.

Reza Baraheni was an Iranian novelist, poet, critic, and political activist.

Mirza Abol-Qasem Qa'em-Maqam Farahani, also known as Qa'em-Maqam II, was an Iranian official and prose writer, who played a central role in Iranian politics in first half of the 19th-century, as well as in Persian literature.

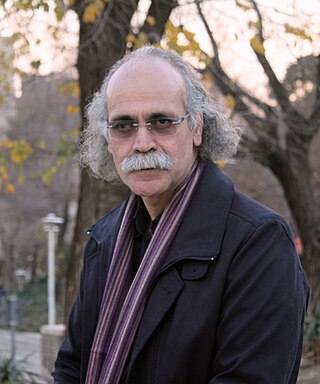

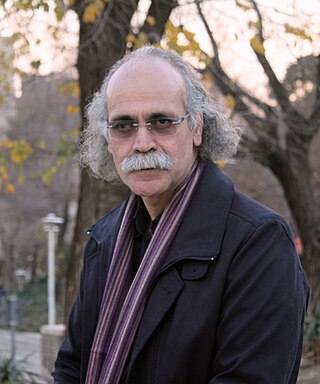

Ghadam-Ali Sarami is an Iranian author and poet. He was born in Ramhormoz, a small town in Khuzestan Province, southwest of Iran. In 1986, he received a Ph.D. in Persian language and literature from University of Tehran, Iran. He is an associate professor of Persian language and literature at University of Zanjan and an expert in Ferdowsi's Shahnameh, Tarikh-i Bayhaqi, and Hafez, Sa'di, Rumi, and other masters of Persian literature and poetry.

Sepideh Jodeyri is an Iranian poet, literary critic, translator and journalist living in Washington DC, United States.

Bahman Sholevar is an Iranian-American novelist, poet, translator, critic, psychiatrist and political activist. He began writing and translating at age 13. At ages 18 and 19 he translated William Faulkner's The Sound and the Fury and T. S. Eliot's The Waste Land into Persian, and these still are renowned as two classics of translation in modern Persian literature. In 1967, after his first novel The Night's Journey was banned in Iran, he immigrated to the United States and in 1981 he became a dual citizen of the United States and Iran. Although most of his writings in the past 42 years have been in English, published outside Iran; although The Night's Journey has never been allowed republication, though sold in thousands of unlicensed copies; and although the Persian version of his last novel, Dead Reckoning, has never been given a "publication permit" in Iran, at their latest re-appraisals some Iranian critics have named him "the most influential Persian writer of the past four decades," "one who has had the most influence on the writers of the younger generations."

Granaz Moussavi is an Iranian-Australian contemporary poet, film director and screenwriter. She is known for her avant-garde poetry in the 1990s. Her debut feature film My Tehran for Sale (2009) is an internationally-acclaimed Australian-Iranian co-production.

Mohsen Emadi is an Iranian-Mexican poet, translator and filmmaker. Born and raised in Iran, he left for Finland in 2009 and has resided primarily in Mexico since 2012, working as a lecturer and researcher in poetry and comparative literature for various institutes in the country.

Kavoos Hasanli, born May 22, 1962, in Qanat-e-No in Iran, is poet, critic and professor at Shiraz University.

Mohammad Sharif Saiidi is a poet from Afghanistan.

Ali Babachahi is an Iranian poet, writer, researcher, and literary critic.

Farhad Hasanzadeh is an Iranian author and poet known for his children's and adolescent literature.

Majid Naficy, also spelled "Majid Nafisi" and "Madjid Nafissi," is an Iranian-American poet. He was the youngest member of the literary circle Jong-e Isfahan and considered the Arthur Rimbaud of Persian poetry in late 1960s in Iran. He was a member of the Confederation of Iranian Students in Los Angeles in 1971, and a member of the independent Marxist Peykar Organization after the Iranian Revolution from August 1979 until spring 1982.

Anarchism in Iran has its roots in a number of dissident religious philosophies, as well as in the development of anti-authoritarian poetry throughout the rule of various imperial dynasties over the country. In the modern era, anarchism came to Iran during the late 19th century and rose to prominence in the wake of the Constitutional Revolution, with anarchists becoming leading members of the Jungle Movement that established the Persian Socialist Soviet Republic in Gilan.