Suleiman I, commonly known as Suleiman the Magnificent in Western Europe and Suleiman the Lawgiver in his Ottoman realm, was the longest-reigning sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1520 until his death in 1566. Under his administration, the Ottoman Empire ruled over at least 25 million people.

Ibrahim was the sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1640 until 1648. He was born in Constantinople, the son of sultan Ahmed I by Kösem Sultan, an ethnic Greek originally named Anastasia.

The siege of Vienna, in 1529, was the first attempt by the Ottoman Empire to capture the capital city of Vienna, Austria, Holy Roman Empire. Suleiman the Magnificent, sultan of the Ottomans, attacked the city with over 100,000 men, while the defenders, led by Niklas Graf Salm, numbered no more than 21,000. Nevertheless, Vienna was able to survive the siege, which ultimately lasted just over two weeks, from 27 September to 15 October, 1529.

Sokollu Mehmed Pasha was an Ottoman statesman of Serbian origin most notable for being the Grand Vizier of the Ottoman Empire. Born in Ottoman Herzegovina into an Orthodox Christian family, Mehmed was recruited as a young boy as part of so called "blood tax" to serve as a janissary to the Ottoman devşirme system of recruiting Christian boys to be raised as officers or administrators for the state. He rose through the ranks of the Ottoman imperial system, eventually holding positions as commander of the imperial guard (1543–1546), High Admiral of the Fleet (1546–1551), Governor-General of Rumelia (1551–1555), Third Vizier (1555–1561), Second Vizier (1561–1565), and as Grand Vizier under three sultans: Suleiman the Magnificent, Selim II, and Murad III. He was assassinated in 1579, ending his near 15-years of service to several Sultans, as sole legal representative in the administration of state affairs.

Andrea Gritti was the Doge of the Venetian Republic from 1523 to 1538, following a distinguished diplomatic and military career. He started out as a successful merchant in Constantinople and transitioned into the position of Bailo, a diplomatic role. He was arrested for espionage but was spared execution thanks to his good relationship with the Ottoman vizier. After being freed from imprisonment, he returned to Venice and began his political career. When the War of the League of Cambrai broke out, despite his lack of experience, he was given a leadership role in the Venetian military, where he excelled. After the war, he was elected Doge, and he held that post until his death.

Pargalı Ibrahim Pasha, also known as Frenk Ibrahim Pasha, Makbul Ibrahim Pasha, which later changed to Maktul Ibrahim Pasha after his execution in the Topkapı Palace, was the first Grand Vizier of the Ottoman Empire appointed by Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent.

The Classical Age of the Ottoman Empire concerns the history of the Ottoman Empire from the conquest of Constantinople in 1453 until the second half of the sixteenth century, roughly the end of the reign of Suleiman the Magnificent. During this period a system of patrimonial rule based on the absolute authority of the sultan reached its apex, and the empire developed the institutional foundations which it would maintain, in modified form, for several centuries. The territory of the Ottoman Empire greatly expanded, and led to what some historians have called the Pax Ottomana. The process of centralization undergone by the empire prior to 1453 was brought to completion in the reign of Mehmed II.

George Martinuzzi, O.S.P., was a Croatian nobleman, Pauline monk and Hungarian statesman who supported King John Zápolya and his son, King John Sigismund Zápolya. He was Bishop of Nagyvárad, Archbishop of Esztergom and a cardinal.

Petru Rareș, sometimes known as Petryła or Peter IV, was twice voivode of Moldavia: 20 January 1527 to 18 September 1538 and 19 February 1541 to 3 September 1546. He was an illegitimate child born to Stephen the Great. His mother was Maria Răreșoaia of Hârlău, whose existence is not historically documented but who is said to have been the wife of a wealthy boyar fish-merchant nicknamed Rareș "rare-haired". Rareș thus was not Petru's actual name but a nickname of his mother's husband.

Piali Pasha was an Ottoman Grand Admiral between 1553 and 1567, and a Vizier (minister) after 1568. He is also known as Piale Pasha in English.

The Habsburg monarchy and the Ottoman Empire waged a series of wars on the territory of the Kingdom of Hungary and several adjacent lands in Southeastern Europe from 1526 to 1568. The Habsburgs and the Ottomans engaged in a series of military campaigns against one another in Hungary between 1526 and 1568. While overall the Ottomans had the upper hand, the war failed to produce any decisive result. The Ottoman army remained very powerful in the open field but it often lost a significant amount of time besieging the many fortresses of the Hungarian frontier and its communication lines were now dangerously overstretched. At the end of the conflict, Hungary had been split into several different zones of control, between the Ottomans, Habsburgs, and Transylvania, an Ottoman vassal state. The simultaneous war of succession between Habsburg-controlled western "Royal Hungary" and the Zápolya-ruled pro-Ottoman "Eastern Hungarian Kingdom" is known as the Little War in Hungary.

Rüstem Pasha was an Ottoman statesman who served as Grand Vizier to Sultan Süleyman the Magnificent. Rüstem Pasha is also known as Damat Rüstem Pasha as a result of his marriage to the sultan's daughter, Mihrimah Sultan, in 1539. He is regarded as one of the most influential and successful grand viziers of the Ottoman Empire.

Antonio Rincon, also Antoine de Rincon, was a Spanish-born diplomat in the service of France. An influential envoy from the King of France to Sultan Suleiman I of the Ottoman Empire, he made various missions to Constantinople between 1530 and 1541. While an effective diplomat, Rincon's enemies considered him a renegade and some later observers would criticize him for promoting Machiavellian policies.

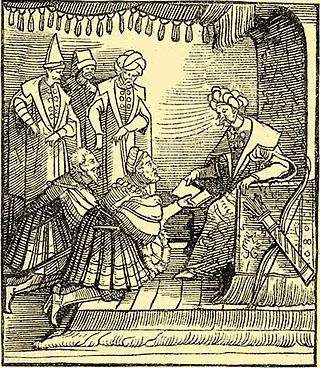

Hieronymus Jarosław Laski, Lasky, Laszki, Laszky, Laskó, Jeromos, Jerome, Hieronym, Hieronim, was a Polish diplomat born of an illustrious Polish family. Laski was the nephew of Archbishop John Laski and served as palatine of Inowrocław and of Sieradz.

The Truce of Constantinople was signed on 22 July 1533 in Constantinople by the Ottoman Empire and the Archduchy of Austria.

This article presents a detailed timeline of the history of the Republic of Venice from its legendary foundation to its collapse under the efforts of Napoleon.

The siege of Kőszeg or siege of Güns, also known as the German campaign was a siege of Kőszeg in the Kingdom of Hungary within the Habsburg Empire, that took place in 1532. In the siege, the defending forces of the Austrian Habsburg monarchy under the leadership of Croatian Captain Nikola Jurišić, defended the small border fort of Kőszeg with only 700–800 Croatian soldiers, with no cannons and few guns. The defenders prevented the advance of the Ottoman army of over 100,000 toward Vienna, under the leadership of Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent and Pargalı Ibrahim Pasha.

Süleyman the Magnificent's Venetian helmet was an elaborate headpiece designed to project the sultan's power in the context of the Ottoman–Habsburg rivalry. It was acquired by the sultan in 1532. The rivalry with the Habsburg monarchy was one of the most significant political and military relationships addressed by the sultan during his reign. In addition to military campaigns, Süleyman also took political and diplomatic steps in order to advance the Ottoman position, promoting trade with European powers and purchasing expensive jewels such as the helmet. The key figures behind the purchase of the helmet were Grand Vizier Ibrahim Pasha and his chief advisors, İskender Çelebi, the chief treasurer, and Alvise Gritti, a powerful jewellery merchant based in the Ottoman capital Konstantinyye, or Istanbul, as it was renamed in 1930.

János Statileo was a writer, bishop of Transylvania, and a diplomat at the court of King Louis II of Hungary and John Zápolya. He was an uncle of Antun Vrančić.

The siege of Buda in 1530 was a failed attempt to capture Buda from the Ottomans by Ferdinand I.