The gambler's fallacy, also known as the Monte Carlo fallacy or the fallacy of the maturity of chances, is the incorrect belief that, if an event has occurred more frequently than expected, it is less likely to happen again in the future. The fallacy is commonly associated with gambling, where it may be believed, for example, that the next dice roll is more than usually likely to be six because there have recently been fewer than the expected number of sixes.

Amos Nathan Tversky was an Israeli cognitive and mathematical psychologist and a key figure in the discovery of systematic human cognitive bias and handling of risk.

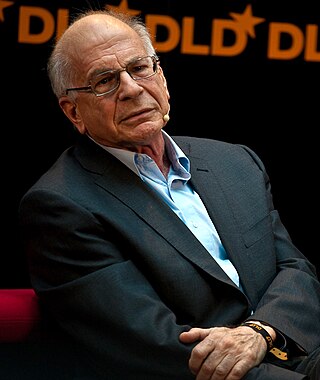

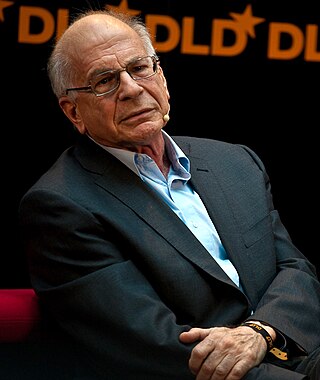

Prospect theory is a theory of behavioral economics, judgment and decision making that was developed by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky in 1979. The theory was cited in the decision to award Kahneman the 2002 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics.

Decision theory is a branch of applied probability theory and analytic philosophy concerned with the theory of making decisions based on assigning probabilities to various factors and assigning numerical consequences to the outcome.

Loss aversion is a psychological and economic concept which refers to how outcomes are interpreted as gains and losses where losses are subject to more sensitivity in people's responses compared to equivalent gains acquired. Kahneman and Tversky (1992) have suggested that losses can be twice as powerful, psychologically, as gains. When defined in terms of the utility function shape as in the cumulative prospect theory (CPT), losses have a steeper utility than gains, thus being more "painful" than the satisfaction from a comparable gain as shown in Figure 1. Loss aversion was first proposed by Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman as an important framework for prospect theory – an analysis of decision under risk.

The expected utility hypothesis is a foundational assumption in mathematical economics concerning decision making under uncertainty. It postulates that rational agents maximize utility, meaning the subjective desirability of their actions. Rational choice theory, a cornerstone of microeconomics, builds this postulate to model aggregate social behaviour.

Status quo bias is an emotional bias; a preference for the maintenance of one's current or previous state of affairs, or a preference to not undertake any action to change this current or previous state. The current baseline is taken as a reference point, and any change from that baseline is perceived as a loss or gain. Corresponding to different alternatives, this current baseline or default option is perceived and evaluated by individuals as a positive.

In prospect theory, the pseudocertainty effect is the tendency for people to perceive an outcome as certain while it is actually uncertain in multi-stage decision making. The evaluation of the certainty of the outcome in a previous stage of decisions is disregarded when selecting an option in subsequent stages. Not to be confused with certainty effect, the pseudocertainty effect was discovered from an attempt at providing a normative use of decision theory for the certainty effect by relaxing the cancellation rule.

In economics, Knightian uncertainty is a lack of any quantifiable knowledge about some possible occurrence, as opposed to the presence of quantifiable risk. The concept acknowledges some fundamental degree of ignorance, a limit to knowledge, and an essential unpredictability of future events.

In decision theory, the Ellsberg paradox is a paradox in which people's decisions are inconsistent with subjective expected utility theory. John Maynard Keynes published a version of the paradox in 1921. Daniel Ellsberg popularized the paradox in his 1961 paper, "Risk, Ambiguity, and the Savage Axioms". It is generally taken to be evidence of ambiguity aversion, in which a person tends to prefer choices with quantifiable risks over those with unknown, incalculable risks.

Omission bias is the phenomenon in which people prefer omission (inaction) over commission (action) and people tend to judge harm as a result of commission more negatively than harm as a result of omission. It can occur due to a number of processes, including psychological inertia, the perception of transaction costs, and the perception that commissions are more causal than omissions. In social political terms the Universal Declaration of Human Rights establishes how basic human rights are to be assessed in article 2, as "without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status." criteria that are often subject to one or another form of omission bias. It is controversial as to whether omission bias is a cognitive bias or is often rational. The bias is often showcased through the trolley problem and has also been described as an explanation for the endowment effect and status quo bias.

In decision theory and economics, ambiguity aversion is a preference for known risks over unknown risks. An ambiguity-averse individual would rather choose an alternative where the probability distribution of the outcomes is known over one where the probabilities are unknown. This behavior was first introduced through the Ellsberg paradox.

In decision theory, on making decisions under uncertainty—should information about the best course of action arrive after taking a fixed decision—the human emotional response of regret is often experienced, and can be measured as the value of difference between a made decision and the optimal decision.

The framing effect is a cognitive bias in which people decide between options based on whether the options are presented with positive or negative connotations. Individuals have a tendency to make risk-avoidant choices when options are positively framed, while selecting more loss-avoidant options when presented with a negative frame. In studies of the bias, options are presented in terms of the probability of either losses or gains. While differently expressed, the options described are in effect identical. Gain and loss are defined in the scenario as descriptions of outcomes, for example, lives lost or saved, patients treated or not treated, monetary gains or losses.

In simple terms, risk is the possibility of something bad happening. Risk involves uncertainty about the effects/implications of an activity with respect to something that humans value, often focusing on negative, undesirable consequences. Many different definitions have been proposed. The international standard definition of risk for common understanding in different applications is "effect of uncertainty on objectives".

Heuristics is the process by which humans use mental shortcuts to arrive at decisions. Heuristics are simple strategies that humans, animals, organizations, and even machines use to quickly form judgments, make decisions, and find solutions to complex problems. Often this involves focusing on the most relevant aspects of a problem or situation to formulate a solution. While heuristic processes are used to find the answers and solutions that are most likely to work or be correct, they are not always right or the most accurate. Judgments and decisions based on heuristics are simply good enough to satisfy a pressing need in situations of uncertainty, where information is incomplete. In that sense they can differ from answers given by logic and probability.

Risk aversion is a preference for a sure outcome over a gamble with higher or equal expected value. Conversely, rejection of a sure thing in favor of a gamble of lower or equal expected value is known as risk-seeking behavior.

The description-experience gap is a phenomenon in experimental behavioral studies of decision making. The gap refers to the observed differences in people's behavior depending on whether their decisions are made towards clearly outlined and described outcomes and probabilities or whether they simply experience the alternatives without having any prior knowledge of the consequences of their choices.

The uncertainty effect, also known as direct risk aversion, is a phenomenon from economics and psychology which suggests that individuals may be prone to expressing such an extreme distaste for risk that they ascribe a lower value to a risky prospect than its worst possible realization.