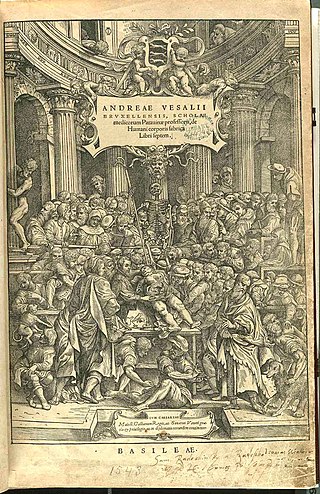

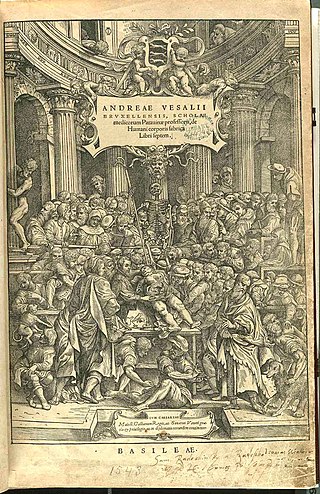

Andreas Vesalius was a 16th-century anatomist, physician, and author of one of the most influential books on human anatomy, De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem, a major advance over the long-dominant work of Galen. Vesalius is often referred to as the founder of modern human anatomy. He was born in Brussels, which was then part of the Habsburg Netherlands. He was a professor at the University of Padua (1537–1542) and later became Imperial physician at the court of Emperor Charles V.

The history of anatomy extends from the earliest examinations of sacrificial victims to the sophisticated analyses of the body performed by modern anatomists and scientists. Written descriptions of human organs and parts can be traced back thousands of years to ancient Egyptian papyri, where attention to the body was necessitated by their highly elaborate burial practices.

Giovanni Filippo Ingrassia or Ioannis Philippi Ingrassiae (1510–1580) was an Italian physician, student of Vesalius, professor at the University of Naples, Protomedicus of Sicily and a major figure in the history of medicine and human anatomy.

Girolamo Fabrici d'Acquapendente, also known as Girolamo Fabrizio or Hieronymus Fabricius, was a pioneering anatomist and surgeon known in medical science as "The Father of Embryology."

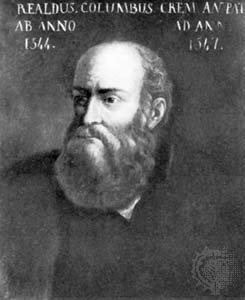

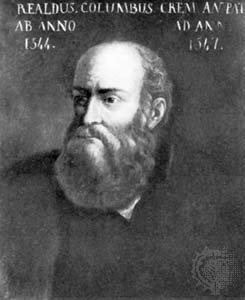

Matteo Realdo Colombo was an Italian professor of anatomy and a surgeon at the University of Padua between 1544 and 1559.

The University of Padua is an Italian university located in the city of Padua, region of Veneto, northern Italy. The University of Padua was founded in 1222 by a group of students and teachers from Bologna. Padua is the second-oldest university in Italy and the world's fifth-oldest surviving university. In 2010, the university had approximately 65,000 students. In 2021, it was ranked second "best university" among Italian institutions of higher education with more than 40,000 students according to Censis institute, and among the best 200 universities in the world according to ARWU.

Moulage is the art of applying mock injuries for the purpose of training emergency response teams and other medical and military personnel. Moulage may be as simple as applying pre-made rubber or latex "wounds" to a healthy "patient's" limbs, chest, head, etc., or as complex as using makeup and theatre techniques to provide elements of realism to the training simulation. The practice dates to at least the Renaissance, when wax figures were used for this purpose.

Giovanni Battista Morgagni was an Italian anatomist, generally regarded as the father of modern anatomical pathology, who taught thousands of medical students from many countries during his 56 years as Professor of Anatomy at the University of Padua.

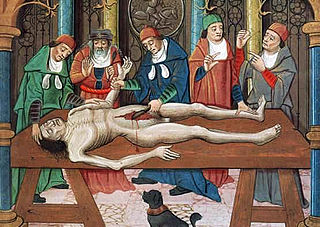

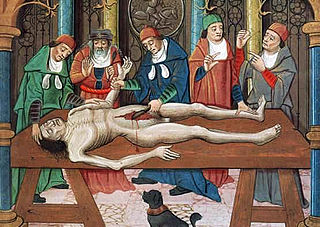

Dissection is the dismembering of the body of a deceased animal or plant to study its anatomical structure. Autopsy is used in pathology and forensic medicine to determine the cause of death in humans. Less extensive dissection of plants and smaller animals preserved in a formaldehyde solution is typically carried out or demonstrated in biology and natural science classes in middle school and high school, while extensive dissections of cadavers of adults and children, both fresh and preserved are carried out by medical students in medical schools as a part of the teaching in subjects such as anatomy, pathology and forensic medicine. Consequently, dissection is typically conducted in a morgue or in an anatomy lab.

Alessandro Achillini was an Italian philosopher and physician. He is known for the anatomic studies that he was able to publish, made possible by a 13th-century edict putatively by Emperor Frederick II allowing for dissection of human cadavers, and which previously had stimulated the anatomist Mondino de Luzzi at Bologna.

An anatomical theatre was a specialised building or room, resembling a theatre, used in teaching anatomy at early modern universities. They were typically constructed with a tiered structure surrounding a central table, allowing a larger audience to see the dissection of cadavers more closely than would have been possible in a non-specialized setting.

The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp is a 1632 oil painting on canvas by Rembrandt housed in the Mauritshuis museum in The Hague, the Netherlands. It was originally created to be displayed by the Surgeons Guild in their meeting room. The painting is regarded as one of Rembrandt's early masterpieces.

Juan Valverde de Amusco was born in the Crown of Castille in what is now Spain c. 1525 and studied medicine in Padua and Rome under Realdo Columbo and Bartolomeo Eustachi. He published several works on anatomy, including De animi et corporis sanitate tuenda libellus.

A cadaver or corpse is a dead human body. Cadavers are used by medical students, physicians and other scientists to study anatomy, identify disease sites, determine causes of death, and provide tissue to repair a defect in a living human being. Students in medical school study and dissect cadavers as a part of their education. Others who study cadavers include archaeologists and arts students. In addition, a cadaver may be used in developing and the evaluation of surgical instruments.

The Anatomical Theatre of the Archiginnasio is a hall once used for anatomy lectures and displays held at the medical school in Bologna, Italy that used to be located in the Palace of the Archiginnasio, the first unified seat of the University of Bologna. A first anatomical theatre was constructed in 1595, in a different location, but it was replaced by a bigger one built in 1637 in the current location, following the design of the architect Antonio Levanti. The ceiling and the wall decoration were completed from 1647 to 1649 but only the lacunar ceiling dates from this period, with the figure of Apollo, the god of Medicine, in the middle, surrounded by symbolic images of constellations carved in wood.

The Medical Renaissance, from around 1400 to 1700 CE, was a period of progress in European medical knowledge, with renewed interest in the ideas of the ancient Greek and Roman civilizations along with Arabic-Persian medicine, following the translation into Latin of many works from these societies. Medical discoveries during the Medical Renaissance are credited with paving the way for modern medicine.

The Archiginnasio of Bologna is one of the most important buildings in the city of Bologna; once the main building of the University of Bologna, it currently houses the Archiginnasio Municipal Library and the Anatomical Theatre.

An anatomy murder is a murder committed in order to use all or part of the cadaver for medical research or teaching. It is not a medicine murder because the body parts are not believed to have any medicinal use in themselves. The motive for the murder is created by the demand for cadavers for dissection, and the opportunity to learn anatomy and physiology as a result of the dissection. Rumors concerning the prevalence of anatomy murders are associated with the rise in demand for cadavers in research and teaching produced by the Scientific Revolution. During the 19th century, the sensational serial murders associated with Burke and Hare and the London Burkers led to legislation which provided scientists and medical schools with legal ways of obtaining cadavers. Rumors persist that anatomy murders are carried out wherever there is a high demand for cadavers. These rumors, like those concerning organ theft, are hard to substantiate, and may reflect continued, deep-held fears of the use of cadavers as commodities.

Johannes van Horne, Joannis van Horne was a Dutch anatomist best known for his illustrated atlas of myology. He was a professor of anatomy and surgery at Leiden University where his students included Nicolaus Steno.

Giovanni Tumiati was a physician and anatomist, active mainly in his native Ferrara.