Hadrian was Roman emperor from 117 to 138. Hadrian was born in Italica, close to modern Seville in Spain, an Italic settlement in Hispania Baetica; his branch of the Aelia gens, the Aeli Hadriani, came from the town of Hadria in eastern Italy. He was a member of the Nerva-Antonine dynasty.

Antinous, also called Antinoös, was a Greek youth from Bithynia and a favourite and lover of the Roman emperor Hadrian. Following his premature death before his 20th birthday, Antinous was deified on Hadrian's orders, being worshipped in both the Greek East and Latin West, sometimes as a god and sometimes merely as a hero.

A bust is a sculpted or cast representation of the upper part of the human body, depicting a person's head and neck, and a variable portion of the chest and shoulders. The piece is normally supported by a plinth. The bust is generally a portrait intended to record the appearance of an individual, but may sometimes represent a type. They may be of any medium used for sculpture, such as marble, bronze, terracotta, plaster, wax or wood.

The Doryphoros of Polykleitos is one of the best known Greek sculptures of Classical antiquity, depicting a solidly built, muscular, standing warrior, originally bearing a spear balanced on his left shoulder. Rendered somewhat above life-size, the lost bronze original of the work would have been cast circa 440 BC, but it is today known only from later marble copies. The work nonetheless forms an important early example of both Classical Greek contrapposto and classical realism; as such, the iconic Doryphoros proved highly influential elsewhere in ancient art.

An acrolith is a composite sculpture made of stone together with other materials such as wood or inferior stone such as limestone, as in the case of a figure whose clothed parts are made of wood, while the exposed flesh parts such as head, hands, and feet are made of marble. The wood was covered either by drapery or by gilding. This type of statuary was common and widespread in Classical antiquity.

Hadrian's Villa is a UNESCO World Heritage Site comprising the ruins and archaeological remains of a large villa complex built around AD 120 by Roman Emperor Hadrian near Tivoli outside Rome.

The Panhellenion or Panhellenium was a league of Greek city-states established in the year 131–132 AD by the Roman Emperor Hadrian while he was touring the Roman provinces of Greece.

Classical sculpture refers generally to sculpture from Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome, as well as the Hellenized and Romanized civilizations under their rule or influence, from about 500 BC to around 200 AD. It may also refer more precisely a period within Ancient Greek sculpture from around 500 BC to the onset of the Hellenistic style around 323 BC, in this case usually given a capital "C". The term "classical" is also widely used for a stylistic tendency in later sculpture, not restricted to works in a Neoclassical or classical style.

The study of Roman sculpture is complicated by its relation to Greek sculpture. Many examples of even the most famous Greek sculptures, such as the Apollo Belvedere and Barberini Faun, are known only from Roman Imperial or Hellenistic "copies". At one time, this imitation was taken by art historians as indicating a narrowness of the Roman artistic imagination, but, in the late 20th century, Roman art began to be reevaluated on its own terms: some impressions of the nature of Greek sculpture may in fact be based on Roman artistry.

The Antinous Mondragone is a 0.95-metre high marble example of the Mondragone type of the deified Antinous. This colossal head was made sometime in the period between 130 AD to 138 AD and then is believed to have been rediscovered in the early 18th century, near the ruined Roman city, Tusculum. After its rediscovery, it was housed at the Villa Mondragone as a part of the Borghese collection, and in 1807, it was sold to Napoleon Bonaparte; it is now housed in the Louvre in Paris, France.

The Hermes of the Museo Pio-Clementino is an ancient Roman sculpture, part of the Vatican collections, Rome. It was long admired as the Belvedere Antinous, named from its prominent placement in the Cortile del Belvedere. It is now inventory number 907 in the Museo Pio-Clementino.

The Capitoline 'Antinous' is a marble statue of a young nude male found at Hadrian's Villa, Tivoli, during the time when Conte Giuseppe Fede was undertaking the earliest concerted excavations there. It was bought before 1733 by Alessandro Cardinal Albani. To contemporaries it seemed to be the real attraction of his collection. The statue was bought by Pope Clement XII in 1733 and went on to form the nucleus of the Capitoline Museums, Rome, where it remains. The restored left leg and the left arm, with its unexpected rhetorical hand gesture, were provided by Pietro Bracci. In the 18th century it was considered to be one of the most beautiful Roman copies of a Greek statue in the world. It was then thought to represent Hadrian's lover Antinous owing to its fleshy face and physique and downturned look. It was part of the artistic loot taken to Paris under the terms of the Treaty of Tolentino (1797) and remained in Paris 1800–15, when it was returned to Rome after the fall of Napoleon.

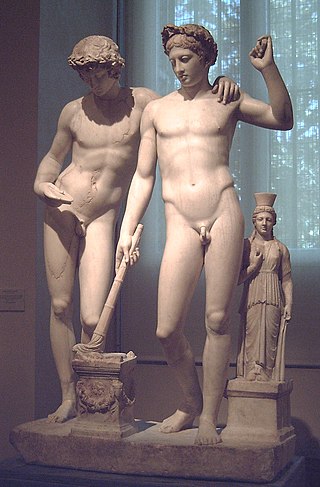

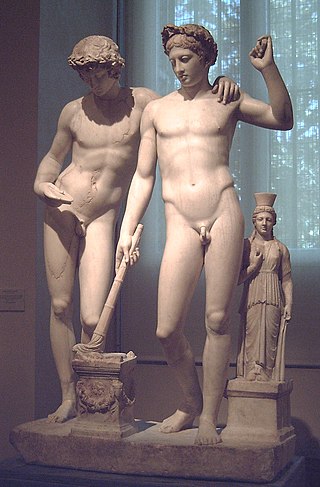

The Castor and Pollux group is an ancient Roman sculptural group of the 1st century AD, now in the Museo del Prado, Madrid.

Antinous was the favorite and lover of Roman Emperor Hadrian.

The Tiber Apollo is an over lifesize marble sculpture of Apollo, a Hadrianic or Antonine Roman marble copy after a bronze Greek original of about 450 BCE. Dredged from the bed of the Tiber in Rome, in making piers for the Ponte Garibaldi.

Treasures of Ancient Rome is a 2012 three-part documentary written and presented by Alastair Sooke. The series was produced by the BBC, and originally aired in September 2012 on BBC Four. In the documentary Sooke sets out to "debunk the myth that Romans didn't do art and were unoriginal". This is based on the view that Romans heavily incorporated Greek style in their art, and hence produced nothing new or original. Sooke has received some criticism from the media because there is no consensus among academics on this topic, and hence no 'myth' exists in the first place.

The Statue of Antinous at Delphi is an ancient statue that was found during excavations in Delphi.

The term Pseudo-athlete is used to describe works of art from the Late Republican period in Rome that combine a veristic head with an idealized body that references Classical Greek sculpture. Verism is a style of Roman portraiture that portrays an individual with aging facial features, most notably sagging skin around the mouth and eyes, short-cropped or balding hair, and deep wrinkles on the forehead and around the eyes and mouth. These features were emphasized under the tradition of verism in order to stress an advanced moral and psychological consciousness that comes along with advanced age. The veristic features of the pseudo-athlete's head are juxtaposed with the figure's body, which is depicted in the guise of an athletic youth from Classical Greece. The pseudo-athlete's body is typically depicted in heroic-nudity with highly smooth muscular forms and are often shown in an active stance or standing in an S-shaped curved known as contrapposto.

The Townley Antinous is a marble portrait head of the Greek youth Antinous, the boyfriend or lover of the Roman Emperor Hadrian, wearing an ivy wreath. It is now part of the collection of London's British Museum, and was part of the Townley Marbles. Only the head is ancient, once belonging to statue dating from c. 130–140 and the late reign of Hadrian ; the bust is a modern addition. The portrait probably shows the youth as Dionysus–Bacchus. The bust was acquired along with the rest of the antiquities collected by 18th-century Grand Tourist and Fellow of the Royal Society, Charles Townley. A drawing of the bust attributed to Vincenzo Pacetti is also in the museum's collection.

The bust of Antinous in the National Archaeological Museum, Athens in Greece is an ancient Roman sculptural portrait of the young Antinous, the favorite and beloved of the Roman emperor Hadrian. It was discovered in the city of Patras in the nineteenth century.