Armillaria is a genus of fungi that includes the A. mellea species known as honey fungi that live on trees and woody shrubs. It includes about 10 species formerly categorized summarily as A. mellea. Armillarias are long-lived and form the largest living fungi in the world. The largest known organism covers more than 3.4 square miles (8.8 km2) in Oregon's Malheur National Forest and is estimated to be 2,500 years old. Some species of Armillaria display bioluminescence, resulting in foxfire.

Texas root rot is a disease that is fairly common in Mexico and the southwestern United States resulting in sudden wilt and death of affected plants, usually during the warmer months. It is caused by a soil-borne fungus named Phymatotrichopsis omnivora that attacks the roots of susceptible plants. It was first discovered in 1888 by Pammel and later named by Duggar in 1916.

Armillaria mellea, commonly known as honey fungus, is an edible basidiomycete fungus in the genus Armillaria. It is a plant pathogen and part of a cryptic species complex of closely related and morphologically similar species. It causes Armillaria root rot in many plant species and produces mushrooms around the base of trees it has infected. The symptoms of infection appear in the crowns of infected trees as discoloured foliage, reduced growth, dieback of the branches and death. The mushrooms are edible but some people may be intolerant to them. This species is capable of producing light via bioluminescence in its mycelium.

Mycelial cords are linear aggregations of parallel-oriented hyphae. The mature cords are composed of wide, empty vessel hyphae surrounded by narrower sheathing hyphae. Cords may look similar to plant roots, and also frequently have similar functions; hence they are also called rhizomorphs. As well as growing underground or on the surface of trees and other plants, some fungi make mycelial cords which hang in the air from vegetation.

Armillaria luteobubalina, commonly known as the Australian honey fungus, is a species of mushroom in the family Physalacriaceae. Widely distributed in southern Australia, the fungus is responsible for a disease known as Armillaria root rot, a primary cause of Eucalyptus tree death and forest dieback. It is the most pathogenic and widespread of the six Armillaria species found in Australia. The fungus has also been collected in Argentina and Chile. Fruit bodies have cream- to tan-coloured caps that grow up to 10 cm (4 in) in diameter and stems that measure up to 20 cm (8 in) long by 1.5 cm (1 in) thick. The fruit bodies, which appear at the base of infected trees and other woody plants in autumn (March–April), are edible, but require cooking to remove the bitter taste. The fungus is dispersed through spores produced on gills on the underside of the caps, and also by growing vegetatively through the root systems of host trees. The ability of the fungus to spread vegetatively is facilitated by an aerating system that allows it to efficiently diffuse oxygen through rhizomorphs—rootlike structures made of dense masses of hyphae.

Armillaria tabescens is a species of fungus in the family Physalacriaceae. It is a plant pathogen. The mycelium of the fungus is bioluminescent.

Ceratocystis fimbriata is a fungus and a plant pathogen, attacking such diverse plants as the sweet potato and the tapping panels of the Para rubber tree. It is a diverse species that attacks a wide variety of annual and perennial plants. There are several host-specialized strains, some of which, such as Ceratocystis platani that attacks plane trees, are now described as distinct species.

Phytophthora cactorum is a fungal-like plant pathogen belonging to the Oomycota phylum. It is the causal agent of root rot on rhododendron and many other species, as well as leather rot of strawberries.

Macrophomina phaseolina is a Botryosphaeriaceae plant pathogen fungus that causes damping off, seedling blight, collar rot, stem rot, charcoal rot, basal stem rot, and root rot on many plant species.

Rhizomorpha subcorticalis is a species name that has been used to characterize certain fungal plant pathogen observations where the pathogen is evident only through mycelial cords ("rhizomorphs"). The species in question very likely also produces reproductive structures which would allow it to be situated in the normal taxonomic tree, especially if DNA analysis is available. A name like R. subcorticalis should only be used where such identification is impossible.

Heterobasidion annosum is a basidiomycete fungus in the family Bondarzewiaceae. It is considered to be the most economically important forest pathogen in the Northern Hemisphere. Heterobasidion annosum is widespread in forests in the United States and is responsible for the loss of one billion U.S. dollars annually. This fungus has been known by many different names. First described by Fries in 1821, it was known by the name Polyporus annosum. Later, it was found to be linked to conifer disease by Robert Hartig in 1874, and was renamed Fomes annosus by H. Karsten. Its current name of Heterobasidion annosum was given by Brefeld in 1888. Heterobasidion annosum causes one of the most destructive diseases of conifers. The disease caused by the fungus is named annosus root rot.

Rosellinia bunodes is a plant pathogen infecting several hosts including avocados, bananas, cacao and tea.

Rigidoporus microporus is a plant pathogen, known to cause white root rot disease on various tropical crops, such as cacao, cassava, tea, with economical importance on the para rubber tree.

Armillaria fuscipes is a plant pathogen that causes Armillaria root rot on Pinus, coffee plants, tea and various hardwood trees. It is common in South Africa. The mycelium of the fungus is bioluminescent.

Laminated root rot also known as yellow ring rot is caused by the fungal pathogen Phellinus weirii. Laminated root rot is one of the most damaging root disease amongst conifers in northwestern America and true firs, Douglas fir, Mountain hemlock, and Western hemlock are highly susceptible to infection with P. weirii. A few species of plants such as Western white pine and Lodgepole pine are tolerant to the pathogen while Ponderosa pine is resistant to it. Only hardwoods are known to be immune to the pathogen.

Armillaria novae-zelandiae is a species of mushroom-forming fungus in the family Physalacriaceae. This plant pathogen species is one of three Armillaria species that have been identified in New Zealand.

Armillaria gallica is a species of honey mushroom in the family Physalacriaceae of the order Agaricales. The species is a common and ecologically important wood-decay fungus that can live as a saprobe, or as an opportunistic parasite in weakened tree hosts to cause root or butt rot. It is found in temperate regions of Asia, North America, and Europe. The species forms fruit bodies singly or in groups in soil or rotting wood. The fungus has been inadvertently introduced to South Africa. Armillaria gallica has had a confusing taxonomy, due in part to historical difficulties encountered in distinguishing between similar Armillaria species. The fungus received international attention in the early 1990s when an individual colony living in a Michigan forest was reported to cover an area of 15 hectares, weigh at least 9.5 tonnes, and be 1,500 years old. This individual is popularly known as the "humongous fungus", and is a tourist attraction and inspiration for an annual mushroom-themed festival in Crystal Falls. Recent studies have revised the fungus's age to 2,500 years and its size to about 400 tonnes, four times the original estimate.

Forest pathology is the research of both biotic and abiotic maladies affecting the health of a forest ecosystem, primarily fungal pathogens and their insect vectors. It is a subfield of forestry and plant pathology.

Armillaria ostoyae is a species of fungus (mushroom), pathogenic to trees, in the family Physalacriaceae. In the western United States, it is the most common variant of the group of species under the name Armillaria mellea. A. ostoyae is common on both hardwood and conifer wood in forests west of the Cascade Range in Oregon, United States. It has decurrent gills and the stipe has a ring. The mycelium invades the sapwood and is able to disseminate over great distances under the bark or between trees in the form of black rhizomorphs ("shoestrings"). In most areas of North America, Armillaria ostoyae can be separated from other species by its physical features: cream-brown colors, prominent cap scales, and a well-developed stem ring distinguish it from other Armillaria.

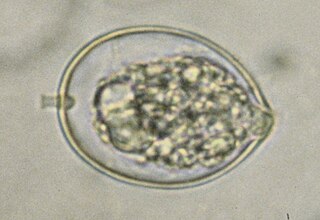

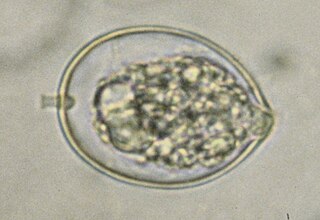

Stromatinia cepivora is a fungus in the division Ascomycota. It is the teleomorph of Sclerotium cepivorum, the cause of white rot in onions, garlic, and leeks. The infective sclerotia remain viable in the soil for many years and are stimulated to germinate by the presence of a susceptible crop.