Minerva is the Roman goddess of wisdom, justice, law, victory, and the sponsor of arts, trade, and strategy. She is also a goddess of warfare, though with a focus on strategic warfare, rather than the violence of gods such as Mars. Beginning in the second century BC, the Romans equated her with the Greek goddess Athena. Minerva is one of the three Roman deities in the Capitoline Triad, along with Jupiter and Juno.

Aquae Sulis was a small town in the Roman province of Britannia. Today it is the English city of Bath, Somerset. The Antonine Itinerary register of Roman roads lists the town as Aquis Sulis. Ptolemy records the town as Aquae calidae in his 2nd-century work Geographia, where it is listed as one of the cities of the Belgae.

The Dobunni were one of the Iron Age tribes living in the British Isles prior to the Roman conquest of Britain. There are seven known references to the tribe in Roman histories and inscriptions.

The Roman Baths are well-preserved thermae in the city of Bath, Somerset, England. A temple was constructed on the site between 60 and 70 AD in the first few decades of Roman Britain. Its presence led to the development of the small Roman urban settlement known as Aquae Sulis around the site. The Roman baths—designed for public bathing—were used until the end of Roman rule in Britain in the 5th century AD. According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, the original Roman baths were in ruins a century later. The area around the natural springs was redeveloped several times during the Early and Late Middle Ages.

In the localised Celtic polytheism practised in Great Britain, Sulis was a deity worshiped at the thermal spring of Bath. She was worshiped by the Romano-British as Sulis Minerva, whose votive objects and inscribed lead tablets suggest that she was conceived of both as a nourishing, life-giving mother goddess and as an effective agent of curses invoked by her votaries.

In ancient Celtic religion, Sulevia was a goddess worshipped in Gaul, Britain, and Galicia, very often in the plural forms Suleviae or (dative) Sule(v)is. Dedications to Sulevia(e) are attested in about forty inscriptions, distributed quite widely in the Celtic world, but with particular concentrations in Noricum, among the Helvetii, along the Rhine, and also in Rome. Jufer and Luginbühl distinguish the Suleviae from another group of plural Celtic goddesses, the Matres, and interpret the name Suleviae as meaning "those who govern well". In the same vein, Patrizia de Bernardo Stempel connects Suleviae with Welsh hylyw 'leading (well)' and Breton helevez 'good behaviour'.

Senuna was a Celtic goddess worshipped in Roman Britain. She was unknown until a cache of 26 votive offerings to her were discovered in 2002 in an undisclosed field at Ashwell End in Hertfordshire by metal detectorist Alan Meek. Her imagery shows evidence of syncretism between a pre-Roman goddess with the Roman Minerva.

In ancient Rome, the apodyterium was the primary entry in the public baths, composed of a large changing room with cubicles or shelves where citizens could store clothing and other belongings while bathing.

A curse tablet is a small tablet with a curse written on it from the Greco-Roman world. Its name originated from the Greek and Latin words for "pierce" and "bind". The tablets were used to ask the gods, place spirits, or the deceased to perform an action on a person or object, or otherwise compel the subject of the curse.

Gallo-Roman religion is a fusion of the traditional religious practices of the Gauls, who were originally Celtic speakers, and the Roman and Hellenistic religions introduced to the region under Roman Imperial rule. It was the result of selective acculturation.

Aquae Arnemetiae was a small town in the Roman province of Britannia. The settlement was based around its natural warm springs. The Roman occupation ran from around 75 AD to 410 AD. Today it is the town of Buxton, Derbyshire in England.

Deva Victrix, or simply Deva, was a legionary fortress and town in the Roman province of Britannia on the site of the modern city of Chester. The fortress was built by the Legio II Adiutrix in the 70s AD as the Roman army advanced north against the Brigantes, and rebuilt completely over the next few decades by the Legio XX Valeria Victrix. In the early 3rd century the fortress was again rebuilt. The legion probably remained at the fortress until the late 4th or early 5th century, upon which it fell into disuse.

According to classical sources, the ancient Celts were animists. They honoured the forces of nature, saw the world as inhabited by many spirits, and saw the Divine manifesting in aspects of the natural world.

The gods and goddesses of the pre-Christian Celtic peoples are known from a variety of sources, including ancient places of worship, statues, engravings, cult objects, and place or personal names. The ancient Celts appear to have had a pantheon of deities comparable to others in Indo-European religion, each linked to aspects of life and the natural world. Epona was an exception and retained without association with any Roman deity. By a process of syncretism, after the Roman conquest of Celtic areas, most of these became associated with their Roman equivalents, and their worship continued until Christianization. Pre-Roman Celtic art produced few images of deities, and these are hard to identify, lacking inscriptions, but in the post-conquest period many more images were made, some with inscriptions naming the deity. Most of the specific information we have therefore comes from Latin writers and the archaeology of the post-conquest period. More tentatively, links can be made between ancient Celtic deities and figures in early medieval Irish and Welsh literature, although all these works were produced well after Christianization.

The Vacomagi were a people of ancient Britain, known only from a single mention of them by the geographer Claudius Ptolemy. Their principal places are known from Ptolemy's map c.150 of Albion island of Britannia – from the First Map of Europe.

Common Brittonic, also known as British, Common Brythonic, or Proto-Brittonic, is an extinct Celtic language spoken in Britain and Brittany.

Niskus is a Romano-British river god, mentioned one time from a lead curse tablet inscription. The theonym is related to a local river deity linked to the River Hamble. It is possible that the origin of the theonym is connected with the ancient Greek word νῆξις - floating. Found on Creek Badnam in Southampton in 1982, this curse tablet from the Greco-Roman world was created in about 350 or 400 AD by Muconius, a man angry at the mystery thief who stole his gold and silver coins.

Roger Simon Ouin Tomlin is a British archaeologist specialising in the translation of Latin text and epigraphy. Tomlin is an Emeritus Fellow of Wolfson College, Oxford.

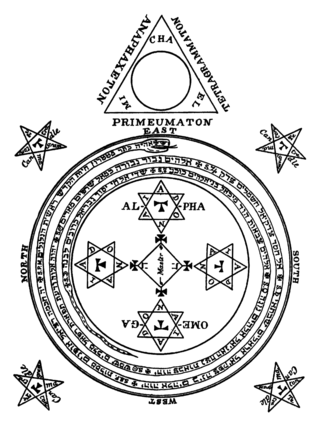

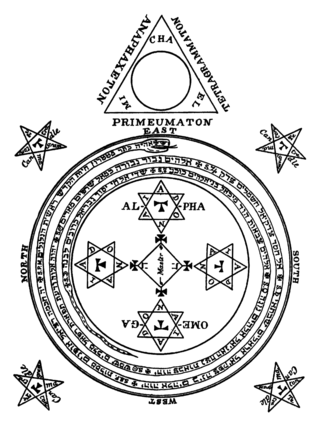

Goetia is a type of European sorcery, often referred to as witchcraft, that has been transmitted through grimoires—books containing instructions for performing magical practices. The term "goetia" finds its origins in the Greek word "goes", which originally denoted diviners, magicians, healers, and seers. Initially, it held a connotation of low magic, implying fraudulent or deceptive mageia as opposed to theurgy, which was regarded as divine magic. Grimoires, also known as "books of spells" or "spellbooks," serve as instructional manuals for various magical endeavors. They cover crafting magical objects, casting spells, performing divination, and summoning supernatural entities like angels, spirits, deities, and demons. Although the term "grimoire" originates from Europe, similar magical texts have been found in diverse cultures across the world.