The Aedui or Haedui were a Gallic tribe dwelling in what is now the region of Burgundy during the Iron Age and the Roman period.

The Boii were a Celtic tribe of the later Iron Age, attested at various times in Cisalpine Gaul, Pannonia, present-day Bavaria, in and around present-day Bohemia, parts of present-day Slovakia and Poland, and Gallia Narbonensis.

The Helvetii, anglicized as Helvetians, were a Celtic tribe or tribal confederation occupying most of the Swiss plateau at the time of their contact with the Roman Republic in the 1st century BC. According to Julius Caesar, the Helvetians were divided into four subgroups or pagi. Of these, Caesar names only the Verbigeni and the Tigurini, while Posidonius mentions the Tigurini and the Tougeni (Τωυγενοί). They feature prominently in the Commentaries on the Gallic War, with their failed migration attempt to southwestern Gaul serving as a catalyst for Caesar's conquest of Gaul.

This article concerns the period 59 BC – 50 BC.

Commentarii de Bello Gallico, also Bellum Gallicum, is Julius Caesar's firsthand account of the Gallic Wars, written as a third-person narrative. In it Caesar describes the battles and intrigues that took place in the nine years he spent fighting the Celtic and Germanic peoples in Gaul that opposed Roman conquest.

Year 58 BC was a year of the pre-Julian Roman calendar. At the time, it was known as the Year of the Consulship of Piso and Gabinius. The denomination 58 BC for this year has been used since the early medieval period, when the Anno Domini calendar era became the prevalent method in Europe for naming years.

The Gallic Wars were waged between 58 and 50 BC by the Roman general Julius Caesar against the peoples of Gaul. Gallic, Germanic, and Brittonic tribes fought to defend their homelands against the aggressive Roman campaign. The Wars culminated in the decisive Battle of Alesia in 52 BC, in which a complete Roman victory resulted in the expansion of the Roman Republic over the whole of Gaul. Though the various collective Gallic armies were as strong as the Roman forces, the Gallic tribes' internal divisions eased victory for Caesar. Gallic chieftain Vercingetorix's attempt to unite the Gauls under a single banner came too late. Caesar portrayed the invasion as being a preemptive and defensive action, but historians agree that he fought the wars primarily to boost his political career and to pay off his debts. Still, Gaul was of significant military importance to the Romans. Native tribes in the region, both Gallic and Germanic, had attacked Rome several times. Conquering Gaul allowed Rome to secure the natural border of the river Rhine.

Legio X Equestris, a Roman legion, was levied by Julius Caesar in 61 BC when he was the Governor of Hispania Ulterior. The Tenth was the first legion levied personally by Caesar and was consistently his most trusted. Legio X was famous in its day and throughout history, because of its portrayal in Caesar's Commentaries and the prominent role the Tenth played in his Gallic campaigns. Its soldiers were discharged in 45 BC. Its remnants were reconstituted, fought for Mark Antony and Octavian, disbanded, and later merged into X Gemina.

The Battle of Alesia or Siege of Alesia was the climactic military engagement of the Gallic Wars, fought around the Gallic oppidum of Alesia in modern France, a major centre of the Mandubii tribe. It was fought by the Roman army of Julius Caesar against a confederation of Gallic tribes united under the leadership of Vercingetorix of the Arverni. It was the last major engagement between Gauls and Romans, and is considered one of Caesar's greatest military achievements and a classic example of siege warfare and investment; the Roman army built dual lines of fortifications – an inner wall to keep the besieged Gauls in, and an outer wall to keep the Gallic relief force out. The Battle of Alesia marked the end of Gallic independence in the modern day territory of France and Belgium.

The Battle of the Sabis, also known as the Battle of the Sambre or the Battle against the Nervians, was fought in 57 BC near modern Saulzoir in Northern France, between Caesar's legions and an association of Belgae tribes, principally the Nervii. Julius Caesar, commanding the Roman forces, was surprised and nearly defeated. According to Caesar's report, a combination of determined defence, skilled generalship, and the timely arrival of reinforcements allowed the Romans to turn a strategic defeat into a tactical victory. Few primary sources describe the battle in detail, with most information coming from Caesar's own report on the battle from his book, Commentarii de Bello Gallico. Little is therefore known about the Nervii perspective on the battle.

Ariovistus was a leader of the Suebi and other allied Germanic peoples in the second quarter of the 1st century BC. He and his followers took part in a war in Gaul, assisting the Arverni and Sequani in defeating their rivals, the Aedui. They then settled in large numbers into conquered Gallic territory, in the Alsace region. They were defeated, however, in the Battle of Vosges and driven back over the Rhine in 58 BC by Julius Caesar.

The Battle of Gergovia took place in 52 BC in Gaul at Gergovia, the chief oppidum of the Arverni. The battle was fought between a Roman Republican army, led by proconsul Julius Caesar, and Gallic forces led by Vercingetorix, who was also the Arverni chieftain. The Romans attempted to besiege Gergovia, but miscommunication ruined the Roman plan. The Gallic cavalry counterattacked the confused Romans and sent them to flight, winning the battle.

Bibracte, a Gallic oppidum, was the capital of the Aedui and one of the most important hillforts in Gaul. It was located near modern Autun in Burgundy, France. The material culture of the Aedui corresponded to the Late Iron Age La Tène culture.

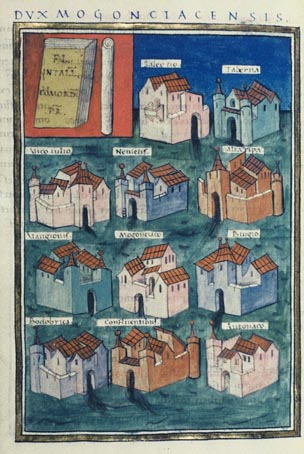

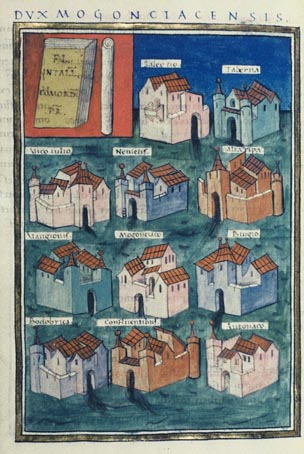

The Vangiones appear first in history as an ancient Germanic tribe of unknown provenance. They threw in their lot with Ariovistus in his bid of 58 BC to invade Gaul through the Doubs river valley and lost to Julius Caesar in a battle probably near Belfort. After some Celts evacuated the region in fear of the Suebi, the Vangiones, who had made a Roman peace, were allowed to settle among the Mediomatrici in northern Alsace.. They gradually assumed control of the Celtic city of Burbetomagus, later Worms.

Dumnorix was a chieftain of the Aedui, a Celtic tribe in Gaul in the 1st century B.C. He was the younger brother of Divitiacus, the Aedui druid and statesman.

The Battle of Vosges, also referred to as the Battle of Vesontio, was fought on September 14, 58 BC between the Germanic tribe of the Suebi, under the leadership of Ariovistus, and six Roman legions under the command of Gaius Julius Caesar. This encounter is the third major battle of the Gallic Wars. Germanic tribes crossed the Rhine, seeking a home in Gaul.

The Rauraci or Raurici were a small Gallic tribe dwelling in the Upper Rhine region, around the present-day city of Basel, during the Iron Age and the Roman period.

Gorgobina was a Celtic oppidum on the territory of the Aedui tribe. After the defeat of the Helvetii in 58 BC at nearby Bibracte, the Helvetians' Boii allies settled there. Whether this really was an act of clemency on Julius Caesar's part may be disputed. With the Aedui being allies of Rome, Vercingetorix besieged Gorgobina in the course of his campaign:

Hac re cognita Vercingetorix rursus in Bituriges exercitum reducit atque inde profectus Gorgobinam, Boiorum oppidum, quos ibi Helvetico proelio victos Caesar collocaverat Haeduisque attribuerat, oppugnare instituit.

(Translation:) With this in mind, Vercingetorix led his army back to the territory of the Bituriges and advanced from there to Gorgobina, the oppidum of the Boii – whom, defeated in the battle of the Helvetians, Caesar had installed there and assigned to the Aedui –, and laid siege to it.

The Tulingi were a small tribe closely allied to the Celtic Helvetii in the time of Julius Caesar's conquest of Gaul. Their location is unknown; their language and descent are uncertain. From their close cooperation with the Helvetii it can be deduced that they were probably neighbours of the latter. At the Battle of Bibracte in 58 BCE, they were, with the Boii and a few other smaller tribes, allies of the Helvetii against the Roman legions of Caesar.