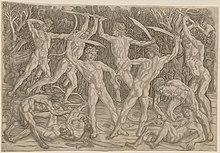

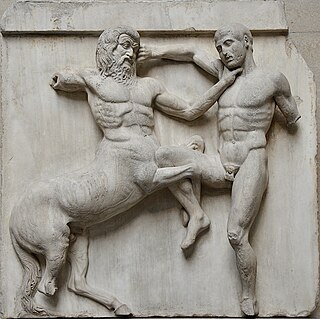

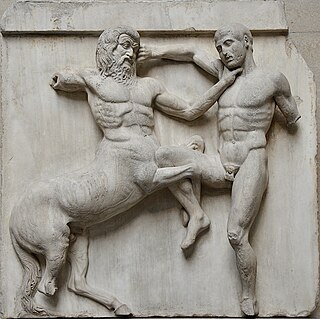

A centaur, occasionally hippocentaur, also called Ixionidae, is a creature from Greek mythology with the upper body of a human and the lower body and legs of a horse that was said to live in the mountains of Thessaly. In one version of the myth, the centaurs were named after Centaurus, and, through his brother Lapithes, were kin to the legendary tribe of the Lapiths.

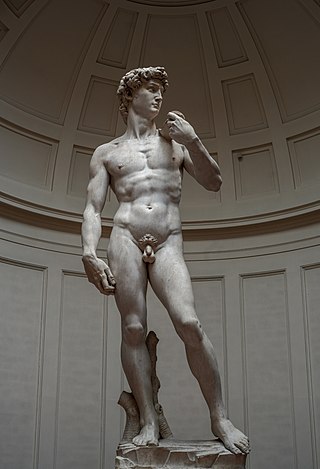

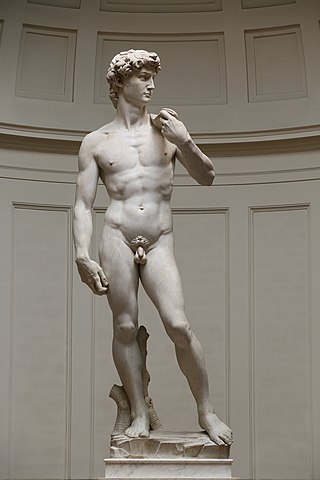

Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni, known as Michelangelo, was an Italian sculptor, painter, architect, and poet of the High Renaissance. Born in the Republic of Florence, his work was inspired by models from classical antiquity and had a lasting influence on Western art. Michelangelo's creative abilities and mastery in a range of artistic arenas define him as an archetypal Renaissance man, along with his rival and elder contemporary, Leonardo da Vinci. Given the sheer volume of surviving correspondence, sketches, and reminiscences, Michelangelo is one of the best-documented artists of the 16th century. He was lauded by contemporary biographers as the most accomplished artist of his era.

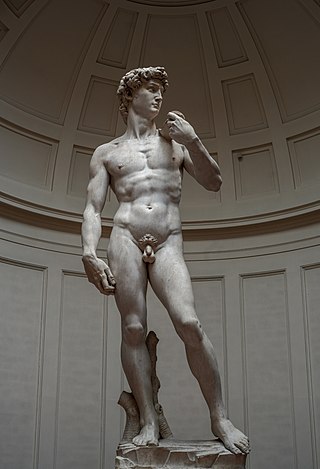

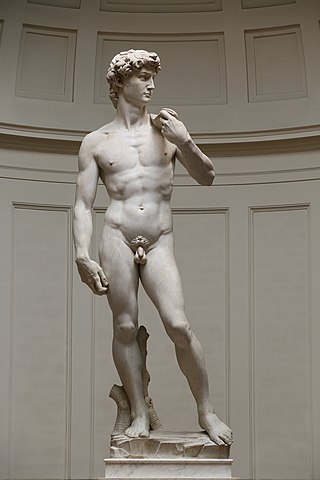

David is a masterpiece of Italian Renaissance sculpture, created from 1501 to 1504 by Michelangelo. With a height of 5.17 metres, the David was the first colossal marble statue made in the early modern period following classical antiquity, a precedent for the 16th century and beyond. David was originally commissioned as one of a series of statues of twelve prophets to be positioned along the roofline of the east end of Florence Cathedral, but was instead placed in the public square in front of the Palazzo della Signoria, the seat of civic government in Florence, where it was unveiled on 8 September 1504. In 1873, the statue was moved to the Galleria dell'Accademia, Florence, and in 1910 replaced at the original location by a replica.

Donato di Niccolò di Betto Bardi, better known as Donatello, was an Italian sculptor of the Renaissance period. Born in Florence, he studied classical sculpture and used his knowledge to develop an Early Renaissance style of sculpture. He spent time in other cities, where he worked on commissions and taught others; his periods in Rome, Padua, and Siena introduced to other parts of Italy the techniques he had developed in the course of a long and productive career. His David was the first freestanding nude male sculpture since antiquity; like much of his work it was commissioned by the Medici family.

Pirithous, in Greek mythology, was the King of the Lapiths of Larissa in Thessaly, as well as best friend to Theseus.

The Lapiths were a group of legendary people in Greek mythology, who lived in Thessaly in the valley of the Peneus and on the mountain Pelion. They were believed to have descended from the mythical Lapithes, brother of Centaurus, with the two heroes giving their names to the races of the Lapiths and the Centaurs respectively. The Lapiths are best known for their involvement in the Centauromachy, a mythical fight that broke out between them and the Centaurs during Pirithous and Hippodamia's wedding.

Giambologna, also known as Jean de Boulogne (French), Jehan Boulongne (Flemish) and Giovanni da Bologna (Italian), was the last significant Italian Renaissance sculptor, with a large workshop producing large and small works in bronze and marble in a late Mannerist style.

The Thinker is a bronze sculpture by Auguste Rodin, usually placed on a stone pedestal. The work depicts a nude male figure of heroic size sitting on a rock. He is seen leaning over, his right elbow placed on his left thigh, holding the weight of his chin on the back of his right hand. The pose is one of deep thought and contemplation, and the statue is often used as an image to represent philosophy.

The Madonna of the Stairs is a relief sculpture by Michelangelo in the Casa Buonarroti, Florence. It was sculpted around 1490, when Michelangelo was about fifteen. This and the Battle of the Centaurs were Michelangelo's first two sculptures. The first reference to the Madonna of the Stairs as a work by Michelangelo was in the 1568 edition of Giorgio Vasari's Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects.

The Agony and the Ecstasy (1961) is a biographical novel of Michelangelo Buonarroti written by American author Irving Stone. Stone lived in Italy for years visiting many of the locations in Rome and Florence, worked in marble quarries, and apprenticed himself to a marble sculptor. A primary source for the novel is Michelangelo's correspondence, all 495 letters of which Stone had translated from Italian by Charles Speroni and published in 1962 as I, Michelangelo, Sculptor. Stone also collaborated with Canadian sculptor Stanley Lewis, who researched Michelangelo's carving technique and tools. The Italian government lauded Stone with several honorary awards for his cultural achievements highlighting Italian history.

Bacchus (1496–1497) is a marble sculpture by the Italian High Renaissance sculptor, painter, architect and poet Michelangelo. The statue is somewhat over life-size and represents Bacchus, the Roman god of wine, in a reeling pose suggestive of drunkenness. Commissioned by Raffaele Riario, a high-ranking Cardinal and collector of antique sculpture, it was rejected by him and was bought instead by Jacopo Galli, Riario's banker and a friend to Michelangelo. Together with the Pietà, the Bacchus is one of only two surviving sculptures from the artist's first period in Rome.

Two different crucifixes, or strictly, wooden corpus figures for crucifixes, are attributed to the High Renaissance master Michelangelo, although neither is universally accepted as his. Both are relatively small figures which would have been produced in Michelangelo's youth.

Bertoldo di Giovanni was an Italian Renaissance sculptor and medallist.

In Greek mythology, Amycus or Amykos was a male centaur and the son of Ophion.

Michelangelo had a complicated relationship with the Medici family, who were for most of his lifetime the effective rulers of his home city of Florence. The Medici rose to prominence as Florence's preeminent bankers. They amassed a sizable fortune some of which was used for patronage of the arts. Michelangelo's first contact with the Medici family began early as a talented teenage apprentice of the Florentine painter Domenico Ghirlandaio. Following his initial work for Lorenzo de' Medici, Michelangelo's interactions with the family continued for decades including the Medici papacies of Pope Leo X and Pope Clement VII.

The Taddei Tondo or The Virgin and Child with the Infant St. John is an unfinished marble relief tondo of the Madonna and Child and the infant Saint John the Baptist, by the Italian Renaissance artist Michelangelo Buonarroti. It is in the permanent collection of the Royal Academy of Arts in London. The tondo is the only marble sculpture by Michelangelo in Great Britain. A "perfect demonstration" of his carving technique, the work delivers a "powerful emotional and narrative punch".

The Tomb of Pope Julius II is a sculptural and architectural ensemble by Michelangelo and his assistants, originally commissioned in 1505 but not completed until 1545 on a much reduced scale. Originally intended for St. Peter's Basilica, the structure was instead placed in the church of San Pietro in Vincoli on the Esquiline in Rome after the pope's death. This church was patronized by the Della Rovere family from which Julius came, and he had been titular cardinal there. Julius II, however, is buried next to his uncle Sixtus IV in St. Peter's Basilica, so the final structure does not actually function as a tomb.

Brutus is a marble bust of Brutus sculpted by Michelangelo around 1539–1540. It is now in the Bargello museum in Florence.

Italian Renaissance sculpture was an important part of the art of the Italian Renaissance, in the early stages arguably representing the leading edge. The example of Ancient Roman sculpture hung very heavily over it, both in terms of style and the uses to which sculpture was put. In complete contrast to painting, there were many surviving Roman sculptures around Italy, above all in Rome, and new ones were being excavated all the time, and keenly collected. Apart from a handful of major figures, especially Michelangelo and Donatello, it is today less well-known than Italian Renaissance painting, but this was not the case at the time.

Renaissance sculpture is understood as a process of recovery of the sculpture of classical antiquity. Sculptors found in the artistic remains and in the discoveries of sites of that bygone era the perfect inspiration for their works. They were also inspired by nature. In this context we must take into account the exception of the Flemish artists in northern Europe, who, in addition to overcoming the figurative style of the Gothic, promoted a Renaissance foreign to the Italian one, especially in the field of painting. The rebirth of antiquity with the abandonment of the medieval, which for Giorgio Vasari "had been a world of Goths", and the recognition of the classics with all their variants and nuances was a phenomenon that developed almost exclusively in Italian Renaissance sculpture. Renaissance art succeeded in interpreting Nature and translating it with freedom and knowledge into a multitude of masterpieces.