Infocom was an American software company based in Cambridge, Massachusetts, that produced numerous works of interactive fiction. They also produced a business application, a relational database called Cornerstone.

Interactive fiction, often abbreviated IF, is software simulating environments in which players use text commands to control characters and influence the environment. Works in this form can be understood as literary narratives, either in the form of Interactive narratives or Interactive narrations. These works can also be understood as a form of video game, either in the form of an adventure game or role-playing game. In common usage, the term refers to text adventures, a type of adventure game where the entire interface can be "text-only", however, graphical text adventure games, where the text is accompanied by graphics still fall under the text adventure category if the main way to interact with the game is by typing text. Some users of the term distinguish between interactive fiction, known as "Puzzle-free", that focuses on narrative, and "text adventures" that focus on puzzles.

Zork is a text adventure game first released in 1977 by developers Tim Anderson, Marc Blank, Bruce Daniels, and Dave Lebling for the PDP-10 mainframe computer. The original developers and others, as the company Infocom, expanded and split the game into three titles—Zork I: The Great Underground Empire, Zork II: The Wizard of Frobozz, and Zork III: The Dungeon Master—which were released commercially for a range of personal computers beginning in 1980. In Zork, the player explores the abandoned Great Underground Empire in search of treasure. The player moves between the game's hundreds of locations and interacts with objects by typing commands in natural language that the game interprets. The program acts as a narrator, describing the player's location and the results of the player's commands. It has been described as the most famous piece of interactive fiction.

Return to Zork is a 1993 graphic adventure game in the Zork series. It was developed by Activision and was the final Zork game to be published under the Infocom label.

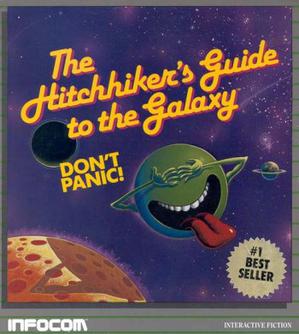

The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy is an interactive fiction video game based on the comedic science fiction series of the same name. It was designed by series creator Douglas Adams and Infocom's Steve Meretzky, and it was first released in 1984 for the Apple II, Mac, Commodore 64, CP/M, MS-DOS, Amiga, Atari 8-bit computers, and Atari ST. It is Infocom's fourteenth game.

Leather Goddesses of Phobos is an interactive fiction video game written by Steve Meretzky and published by Infocom in 1986. It was released for the Amiga, Amstrad CPC, Amstrad PCW, Apple II, Mac, Atari 8-bit computers, Atari ST, Commodore 64, TI-99/4A, and MS-DOS. The game was Infocom's first "sex farce", including selectable gender and "naughtiness"—the latter ranging from "tame" to "lewd". It was one of five top-selling Infocom titles to be re-released in Solid Gold versions. It was Infocom's twenty-first game.

Wishbringer: The Magick Stone of Dreams is an interactive fiction video game written by Brian Moriarty and published by Infocom in 1985. It was intended to be an easier game to solve than the typical Infocom release and provide a good introduction to interactive fiction for inexperienced players, and was well received.

The Lost Treasures of Infocom is a 1991 compilation of 20 previously-released interactive fiction games developed by Infocom. It was published by Activision for MS-DOS, Macintosh, Amiga, and Apple IIGS versions. It was later re-released on CD-ROM, and in 2012 on iOS.

Zork: Grand Inquisitor is a graphic adventure game developed and published by Activision, and released for Windows in 1997; a second edition for Macintosh was released in 2001. The game is the twelfth in the Zork series, and builds upon both this and the Enchanter series of interactive fiction video games originally released by Infocom. The game's story focuses on the efforts of a salesperson who becomes involved in restoring magic to Zork while thwarting the plots of a tyrannical figure seeking to stop this. The game features the performances of Erick Avari, Michael McKean, Amy D. Jacobson, Marty Ingels, Earl Boen, Jordana Capra, Dirk Benedict, David Lander and Rip Taylor.

Enchanter is an interactive fiction game written by Marc Blank and Dave Lebling and published by Infocom in 1983. The first fantasy game published by Infocom after the Zork trilogy, it was originally intended to be Zork IV. The game has a parser that understands over 700 words, making it the most advanced interactive fiction game of its time. It was Infocom's ninth game.

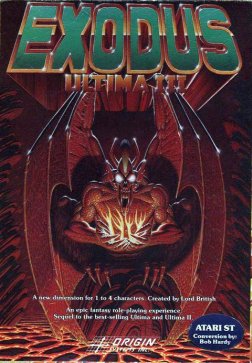

Ultima III: Exodus is the third game in the series of Ultima role-playing video games. Exodus is also the name of the game's principal antagonist. It is the final installment in the "Age of Darkness" trilogy. Released in 1983, it was the first Ultima game published by Origin Systems. Originally developed for the Apple II, Exodus was eventually ported to 13 other platforms, including a NES/Famicom remake.

The Bard's Tale II: The Destiny Knight is a fantasy role-playing video game created by Interplay Productions in 1986. It is the first sequel to The Bard's Tale, and the last game of the series that was designed and programmed by Michael Cranford.

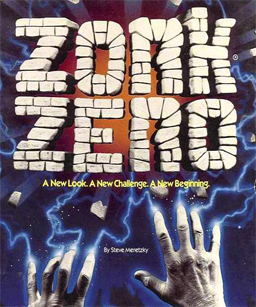

Zork Zero: The Revenge of Megaboz is an interactive fiction computer game, written by Steve Meretzky over nearly 18 months and published by Infocom in 1988. Although it is the ninth and last Zork game released by Infocom before the company's closure, Zork Zero takes place before the previous eight games. Unlike its predecessors, Zork Zero is a vast game, featuring a graphical interface with scene-based colors and borders, an interactive map, menus, an in-game hints system, an interactive Encyclopedia Frobozzica, and playable graphical mini-games. The graphics were created by computer artist James Shook. It is Infocom's thirty-second game.

Spellbreaker is an interactive fiction video game written by Dave Lebling and published by Infocom in 1985, the third and final game in the "Enchanter Trilogy." It was released for the Amiga, Amstrad CPC, Apple II, Atari 8-bit computers, Atari ST, Commodore 64, Classic Mac OS, and MS-DOS. Infocom's nineteenth game, Spellbreaker is rated "Expert" difficulty.

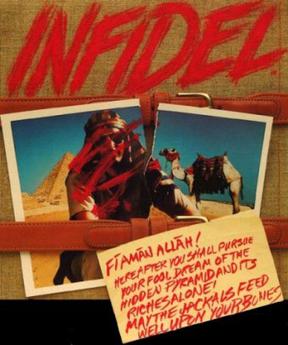

Infidel is an interactive fiction video game published by Infocom in 1983. It was written and designed by Michael Berlyn and Patricia Fogleman, and was the first in the "Tales of Adventure" line. It was released for the Amstrad CPC, Apple II, Atari 8-bit computers, Commodore 64, IBM PC compatibles, TRS-80, and TI-99/4A. Ports were later published for Mac, Atari ST, and Amiga. Infidel is Infocom's tenth game.

Wizardry: Proving Grounds of the Mad Overlord is the first game in the Wizardry series of role-playing video games. It was developed by Andrew Greenberg and Robert Woodhead. In 1980, Norman Sirotek formed Sir-Tech Software, Inc. and launched a beta version of the product at the 1980 Boston Computer Convention. The final version of the game was released in 1981.

The Space Bar is a 1997 graphic adventure game developed by Boffo Games and published by Rocket Science Games and SegaSoft. A comic science fiction story, it follows detective Alias Node as he searches for a shapeshifting killer inside The Thirsty Tentacle, a fantastical bar on the planet Armpit VI. The player assumes the role of Alias and uses his Empathy Telepathy power to live out the memories of eight of the bar's patrons, including an immobile plant, an insect with compound eyes and a blind alien who navigates by sound. Gameplay is nonlinear and under a time limit: the player may solve puzzles and gather clues in any order, but must win before the killer escapes the bar.

Quarterstaff: The Tomb of Setmoth is an interactive fiction role-playing video game developed by Scott Schmitz and Ken Updike and released by Infocom for Macintosh in 1988. The game features a text parser, graphics, a dynamically updated map, and a graphical interface that incorporates Mac OS hierarchical menus.

Telengard is a 1982 role-playing dungeon crawler video game developed by Daniel Lawrence and published by Avalon Hill. The player explores a dungeon, fights monsters with magic, and avoids traps in real-time without any set mission other than surviving. Lawrence first wrote the game as DND, a 1976 version of Dungeons & Dragons for the DECsystem-10 mainframe computer. He continued to develop DND at Purdue University as a hobby, rewrote the game for the Commodore PET 2001 after 1978, and ported it to Apple II+, TRS-80, and Atari 800 platforms before Avalon Hill found the game at a convention and licensed it for distribution. Its Commodore 64 release was the most popular. Reviewers noted Telengard's similarity to Dungeons and Dragons. RPG historian Shannon Appelcline noted the game as one of the first professionally produced computer role-playing games, and Gamasutra's Barton considered Telengard consequential in what he deemed "The Silver Age" of computer role-playing games preceding the golden age of the late 1980s. Some of the game's dungeon features, such as altars, fountains, teleportation cubes, and thrones, were adopted by later games such as Tunnels of Doom (1982).

Legends of Zork was a browser-based online adventure game based on the Zork universe created by software company Infocom.