History of the Black Bob Band (Skipakákamithagî’) and the Black Bob Reservation

Black Bob and his Hathawekela band, the Cape Girardeau Shawnee, lived on land controlled by Spain "in eastern Missouri on land granted to them about 1793 by Baron Carondelet, near Cape Girardeau." In 1808, Chief Black Bob and his band "refused to remove with the rest of the tribe to Indian Territory." [2]

The Cape Girardeau band believed that government commissioners had misled them about the 1825 treaty and argued that they had never agreed to allow any Ohio Shawnees to settle on the western lands. As a result, a portion of the Shawnees under the leadership of Black Bob did not move to eastern Kansas and instead settled along the White River in Arkansas. Meanwhile, the Rogerstown and Fish bands traveled directly to eastern Kansas, where successive parties of Ohio Shawnees joined them over the next several years. A more complete reunion in 1833 occurred only through intimidation. Black Bob's band still had no desire to move to the Kansas River. [5] [6]

On Oct. 26, 1831, "General William Clark at Castor Hill in St. Louis County, Missouri, signed a treaty with representatives of the Delaware then in Kansas and the Cape Girardeau Shawnee (the Black Bob band) then in Arkansas, giving up all claim to the Cape Girardeau grant." [6]

The Black Bob band had written directly to President Andrew Jackson, noting that "For the last forty years we have resided in Upper Louisiana," (which was now called Missouri), "peaceably following our usual occupations for the support of our families", explaining that the Shawnee lands in Kansas had "climate colder than we have been accustomed to, or wish to live in," and they would be "surrounded by people strangers to us." However, in 1833, this petition was denied. [7]

Eventually, Black Bob's band "removed to the area of Kansas". In an 1854 treaty with Black Bob, "the United States gave them rights to land on the Shawnee Reservation in that state." [2] The reservation became home to "2,183 Shawnees [from a variety of different bands] ... between 1825 and 1834. This 1.6 million-acre reservation stretched from the confluence of the Kansas and Missouri rivers west toward present-day Topeka. [8]

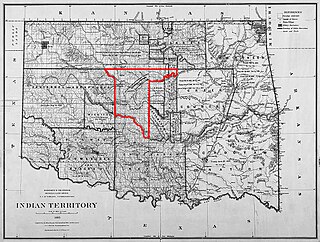

The Black Bob Reservation (or Black Bob Reserve) was located in the southeastern part of Johnson County, Kansas, "at the sources of the Blue and Tomahawk creeks, lying in Oxford, Spring Hill, Aubry and Olathe townships," [9] on 33,000 acres "in the Tomahawk Creek area near the current intersection of 119th and Black Bob [Road]." [10]

The Black Bob Band became known as Skipakákamithagî’ in the Shawnee language, "blue water Indians"; because they lived on the Big Blue River.

Black Bob’s band lived East of Olathe County ... He kept the band together until his death, but 1867 the speculators induced the Indians to get their land in severalty. 1857 there was 136 Black Bob Indians. [3]

During the years of the Civil War, Shawnees from the Absentee-Shawnee and other bands fled to the 33,000 acre Black Bob Reservation as refugees. [5]

A "record of land selections made by members of Black Bob's Band of Shawnee" can be found in the James Burnett Abbott Collection of the Kansas Historical Society. [11] [12]

The tribe held its lands in common until 1866, and "continued to live as had been their custom, making but little progress and spending most of their time in visiting other tribes and hunting, until the breaking out of the [Civil] war. Then, on account of the losses and sufferings to which they were subjected from bushwhackers on one hand, and Kansas thieves on the other, they left their homes and went to the Indian Territory in a body. There they remained until peace was proclaimed, when about one hundred returned to dispose of their lands." [9]

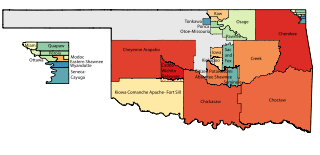

Tribal members petitioned the US Government in the 1870s to "keep their land intact," noting that since the war, the band had been "composed largely of women and children." They also said that it is not their choice to divide their land, but "is an alternative urged on them by speculators who care nothing for our people, only so far as they can use us for selfish purposes." [13] However, these petitions were not successful, the lands were sold to speculators. "The Black Bob Shawnee were expelled from their land ... and moved to Northeastern Oklahoma." [13] There they joined the Absentee-Shawnee, "and claimed acreage assigned the Potawatomi." [14]

Another account states:

The border troubles before and during the Civil War made it impossible for these Shawnees to remain on their land, and they went to the Indian Territory. Squatters took possession of the vacated lands. For a quarter of a century there was no settlement of the matter. Speculators and grafters flourished at the expense of the Indians. The matter was a standing scandal, settled finally by Congress and the Courts, and greatly to the disadvantage of the Black-Bob Shawnee. [15] [16]

A corroborating account which provides more specifics, states:

The Indians to whom the reservation belonged abandoned it near the beginning of the war. As it was most excellent land--fertile soil, well watered and timbered--settlers rushed in at the close of the war and soon every quarter-section of it was occupied by a claimant. This was in the years of 1865 and 1866. About the same time, certain other parties, not actual settlers on the lands, among whom were Gen. James G. Blunt, J. C. Irvin and Judge Pendery, conceived the design of buying up a portion of this land for the purposes of speculation. This was in October, 1867 ...

One author asserts that "Following his term as Indian Agent, Abbott teamed with land speculator H.L. Taylor to acquire some of the Black Bob land holdings. The two then illegally sold portions of their land to new settlers," and refers to a local school assignment titled, "Who Gets the Land?: Competing Visions of Abbott, Bluejacket and Black Bob." [17] [18] "They attempted to sell their lands, but were interfered with by white squatters who claimed the first right to purchase. Matters were tied up in this shape until this act [of Congress] of Mar. 3, 1879." [19]

The squatters on the Black Bob Reservation remained a topic of discussion as late as 1890 in The Indian Chieftain newspaper, published in Vinita, Oklahoma.

BLACK BOB SQUATTERS. A Bill Filed in the Circuit Court to Have Them Ejected. Topeka. Kan. Nov. 15. The United States District Attorney of Kansas, under Instructions from Attorney-General Miller, has just filed a bill in equity in the Circuit Court of the United States at Topeka, on behalf of the Black Bob band of Shawnee Indians sad ajrsinsfc the settlers who have squatted on the Black Bob reservation in Johnson County and the speculators who hold unapproved deeds from the Indians. The bill alleges that the deeds of the speculators were obtained by fraud and demands that they be canceled. The bill prays that the settlers be ejected and that they be held to account to the Indians for the rents and profits of the land for the last twenty years. This suit involves about 39,000 acres of the best land in Johnson County, which have been occupied by squatters ever since the Indians were driven off by Quantrell and his men in 1861.

The settlers have absolutely no title save the possession, which they have been well satisfied to enjoy without any liability to pay taxes. Great excitement prevails among the people on the reservation over the prospects cf being ejected, losing the improvements which they have placed there, and belay, mulcted for rents and profits besides. They have employed attorneys, and will make a bitter fight. The speculators who hold unapproved deeds have never been in possession, having been kept out by the squatters. Might has been right on the reservation for a long time, and for years it has furnished tho courts of Johnson County the largest proportion of their criminal business. The local attorney appointed by Attorney-General Miller to look after the interests of the Indians say: that every prayer of the bill will be insisted upon. [20]