Five Points was a 19th-century neighborhood in Lower Manhattan, New York City. The neighborhood, partly built on low-lying land which had filled in the freshwater lake known as the Collect Pond, was generally defined as being bound by Centre Street to the west, the Bowery to the east, Canal Street to the north, and Park Row to the south. The Five Points gained international notoriety as a densely populated, disease-ridden, crime-infested slum which existed for over 70 years.

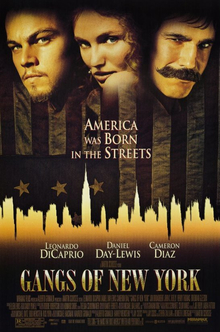

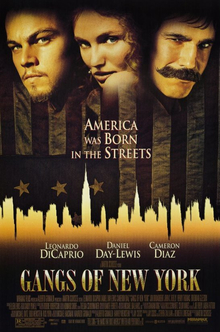

Gangs of New York is a 2002 American historical drama film directed by Martin Scorsese and written by Jay Cocks, Steven Zaillian, and Kenneth Lonergan, based on Herbert Asbury's 1927 book The Gangs of New York. The film stars Leonardo DiCaprio, Daniel Day-Lewis, and Cameron Diaz, along with Jim Broadbent, John C. Reilly, Henry Thomas, Stephen Graham, Eddie Marsan, and Brendan Gleeson in supporting roles.

The Dead End Kids were a group of young actors from New York City who appeared in Sidney Kingsley's Broadway play Dead End in 1935. In 1937, producer Samuel Goldwyn brought all of them to Hollywood and turned the play into a film. They proved to be so popular that they continued to make movies under various monikers, including the Little Tough Guys, the East Side Kids, and the Bowery Boys, until 1958.

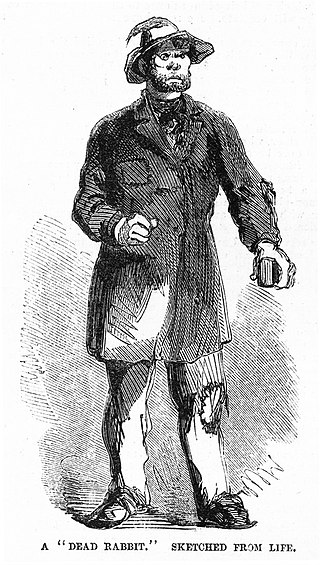

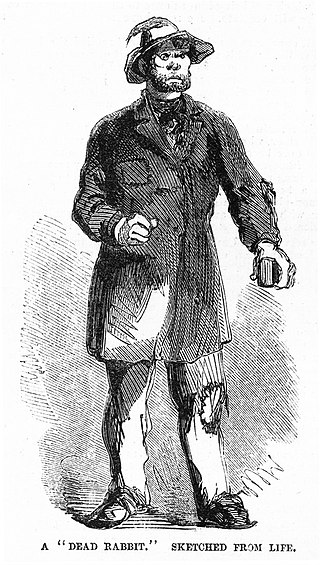

The Dead Rabbits was the name of an Irish American criminal street gang active in Lower Manhattan in the 1830s to 1850s. The Dead Rabbits were so named after a dead rabbit was thrown into the center of the room during a gang meeting, prompting some members to treat this as an omen, withdraw, and form an independent gang. Their battle symbol was a dead rabbit on a pike. They often clashed with Nativist political groups who viewed Irish Catholics as a threatening and criminal subculture. The Dead Rabbits were given the nicknames of "Mulberry Boys" and the "Mulberry Street Boys" by the New York City Police Department because they were known to have operated along Mulberry Street in the Five Points.

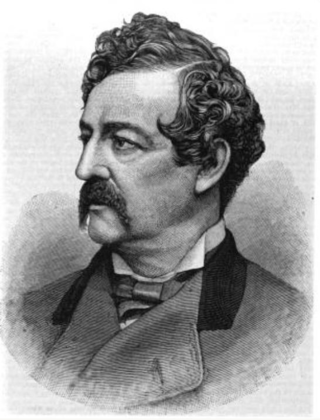

William Poole, also known as Bill the Butcher, was the leader of the Washington Street Gang, which later became known as the Bowery Boys gang. He was a local leader of the Know Nothing political movement in mid-19th-century New York City.

The Roach Guards were an Irish criminal gang in Five Points neighborhood of New York City the early 19th century. The gang was originally formed to protect New York liquor merchants in Five Points and soon began committing robbery and murder. The Roach Guards took their name from their founder and leader Ted Roach.

The Five Points Gang was a criminal street gang of primarily Irish-American origins, based in the Five Points of Lower Manhattan, New York City, during the late 19th and early 20th century.

B'hoy and g'hal were the prevailing slang words used to describe the young men and women of the rough-and-tumble working class culture of Lower Manhattan in the late 1840s and into the period of the American Civil War. They spoke a slang, with phrases such as "hi-hi", "lam him", and "cheese it".

The Bowery Theatre was a playhouse on the Bowery in the Lower East Side of Manhattan, New York City. Although it was founded by rich families to compete with the upscale Park Theatre, the Bowery saw its most successful period under the populist, pro-American management of Thomas Hamblin in the 1830s and 1840s. By the 1850s, the theatre came to cater to immigrant groups such as the Irish, Germans, and Chinese. It burned down four times in 17 years, a fire in 1929 destroying it for good. Although the theatre's name changed several times, it was generally referred to as the "Bowery Theatre".

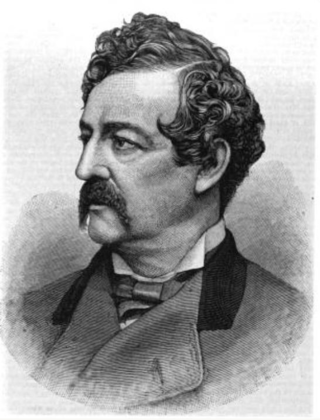

Thomas Souness Hamblin was an English actor and theatre manager. He first took the stage in England, then immigrated to the United States in 1825. He received critical acclaim there, and eventually entered theatre management. During his tenure at New York City's Bowery Theatre he helped establish working-class theatre as a distinct form. His policies preferred American actors and playwrights to British ones, making him an important influence in the development of early American drama.

Francis S. Chanfrau was an American actor and theatre manager in the 19th century. He began his career playing bit parts and doing impressions of star actors such as Edwin Forrest and of ethnic groups.

Timothy Daniel Sullivan was a New York politician who controlled Manhattan's Bowery and Lower East Side districts as a prominent leader within Tammany Hall. He was known euphemistically as "Dry Dollar", as the "Big Feller", and later as "Big Tim" because of his physical stature. He amassed a large fortune as a businessman running vaudeville and legitimate theaters, as well as nickelodeons, race tracks, and athletic clubs.

The Gangs of New York: An Informal History of the Underworld is an American non-fiction book by Herbert Asbury, first published in 1928 by Alfred A. Knopf. It was the basis for Martin Scorsese's 2002 film Gangs of New York.

Mose Humphrey was a member of Fire Company 40 in New York City in the 19th century, and the inspiration for the folk hero character "Mose the Fireboy".

Major General Charles W. Sandford was an American militia and artillery officer, lawyer and businessman. He was a senior officer in the New York State Militia for over thirty years and commanded the First Division in every major civil disturbance in New York City up until the American Civil War, most notably, the New York Draft Riots in 1863.

The Dead Rabbits riot was a two-day civil disturbance in New York City evolving from what was originally a small-scale street fight between members of the Dead Rabbits and the Bowery Boys into a citywide gang war, which occurred July 4–5, 1857. Taking advantage of the disorganized state of the city's police force—brought about by the conflict between the Municipal and Metropolitan police—the fighting spiraled into widespread looting and damage of property by gangsters and other criminals from all parts of the city. It is estimated that between 800 and 1,000 gang members took part in the riots, along with several hundred others who used the disturbance to loot the Bowery area. It was the largest disturbance since the Astor Place Riot in 1849 and the biggest scene of gang violence until the New York Draft Riots of 1863. Order was restored by the New York State Militia, supported by detachments of city police, under Major-General Charles W. Sandford.

Syksey was the pseudonym of an American criminal and member of the Bowery Boys. He was supposedly the lieutenant and longtime companion to Mose the Fireboy during the 1840s, often the storyteller of his feats, and is credited for coining the phrase "hold 'de but", a common expression used during the mid-to late 19th century meaning to borrow a dead cigar or to "bum a smoke". He was later portrayed in Benjamin Baker's play Mose, the Bowery B'hoy which performed at the old Olympic Theater in 1849 and later toured throughout the United States during the late 1840s and 50s. His pseudonym may have been derived from Bill Sikes, the sidekick of gang leader Fagin from Oliver Twist.

Captain Isaiah Rynders was an American businessman, sportsman, underworld figure and political organizer for Tammany Hall. Founder of the Empire Club, a powerful political organization in New York during the mid-19th century, his "sluggers" committed voter intimidation and election fraud on behalf of Tammany Hall throughout the 1840s and 1850s before Tammany became an exclusively Irish-dominated institution.

The East Side Kids were characters in a series of 22 films released by Monogram Pictures from 1940 through 1945. The series was a low-budget imitation of the Dead End Kids, a successful film franchise of the late 1930s.

The Atlantic Guards were a 19th-century American street gang active in New York City from the 1840s to the 1860s. It was one of the original, and among the most important gangs of the early days of the Bowery, along with the Bowery Boys, American Guards, O'Connell Guards, and the True Blue Americans.