The Cuban Missile Crisis, also known as the October Crisis in Cuba, or the Caribbean Crisis, was a 13-day confrontation between the governments of the United States and the Soviet Union, when American deployments of nuclear missiles in Italy and Turkey were matched by Soviet deployments of nuclear missiles in Cuba. The crisis lasted from 16 to 28 October 1962. The confrontation is widely considered the closest the Cold War came to escalating into full-scale nuclear war.

The Partial Test Ban Treaty (PTBT), formally known as the 1963 Treaty Banning Nuclear Weapon Tests in the Atmosphere, in Outer Space and Under Water, prohibited all test detonations of nuclear weapons except for those conducted underground. It is also abbreviated as the Limited Test Ban Treaty (LTBT) and Nuclear Test Ban Treaty (NTBT), though the latter may also refer to the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT), which succeeded the PTBT for ratifying parties.

In nuclear strategy, a first strike or preemptive strike is a preemptive surprise attack employing overwhelming force. First strike capability is a country's ability to defeat another nuclear power by destroying its arsenal to the point where the attacking country can survive the weakened retaliation while the opposing side is left unable to continue war. The preferred methodology is to attack the opponent's strategic nuclear weapon facilities, command and control sites, and storage depots first. The strategy is called counterforce.

Mutual assured destruction (MAD) is a doctrine of military strategy and national security policy which posits that a full-scale use of nuclear weapons by an attacker on a nuclear-armed defender with second-strike capabilities would result in the complete annihilation of both the attacker and the defender. It is based on the theory of rational deterrence, which holds that the threat of using strong weapons against the enemy prevents the enemy's use of those same weapons. The strategy is a form of Nash equilibrium in which, once armed, neither side has any incentive to initiate a conflict or to disarm.

World War III, World War 3, WWIII, WW3, or the Third World War are the names given to a hypothetical global conflict subsequent to World War I and World War II. The term has been in use since as early as 1941. Some apply it loosely to limited or more minor conflicts such as the Cold War or the war on terror. In contrast, others assume that such a conflict would surpass prior world wars in both scope and destructive impact.

The Cold War was a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc, that started in 1947 and lasted to 1991.

The nuclear arms race was an arms race competition for supremacy in nuclear warfare between the United States, the Soviet Union, and their respective allies during the Cold War. During this same period, in addition to the American and Soviet nuclear stockpiles, other countries developed nuclear weapons, though none engaged in warhead production on nearly the same scale as the two superpowers.

The Cold War (1953–1962) discusses the period within the Cold War from the end of the Korean War in 1953 to the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962. Following the death of Joseph Stalin earlier in 1953, new leaders attempted to "de-Stalinize" the Soviet Union causing unrest in the Eastern Bloc and members of the Warsaw Pact. In spite of this there was a calming of international tensions, the evidence of which can be seen in the signing of the Austrian State Treaty reuniting Austria, and the Geneva Accords ending fighting in Indochina. However, this period of good happenings was only partial with an expensive arms race continuing during the period and a less alarming, but very expensive space race occurring between the two superpowers as well. The addition of African countries to the stage of cold war, such as the Democratic Republic of the Congo joining the Soviets, caused even more unrest in the West.

The First Taiwan Strait Crisis was a brief armed conflict between the People's Republic of China (PRC) and the Republic of China (ROC) in Taiwan. The conflict focused on several groups of islands in the Taiwan Strait that were held by the ROC but were located only a few miles from mainland China.

Massive retaliation, also known as a massive response or massive deterrence, is a military doctrine and nuclear strategy in which a state commits itself to retaliate in much greater force in the event of an attack.

Llewellyn E. "Tommy" Thompson Jr. was an American diplomat. He served in Sri Lanka, Austria, and for a lengthy period in the Soviet Union, where his tenure saw some of the most significant events of the Cold War. He was a key advisor to President John F. Kennedy during the Cuban Missile Crisis. A 2019 assessment described him as "arguably the most influential figure who ever advised U.S. presidents about policy toward the Soviet Union during the Cold War."

The New Look was the name given to the national security policy of the United States during the administration of President Dwight D. Eisenhower. It reflected Eisenhower's concern for balancing the Cold War military commitments of the United States with the nation's financial resources. The policy emphasised reliance on strategic nuclear weapons as well as a reorganisation of conventional forces in an effort to deter potential threats, both conventional and nuclear, from the Eastern Bloc of nations headed by the Soviet Union.

The Vienna summit was a summit meeting held on June 4, 1961, in Vienna, Austria, between President of the United States John F. Kennedy and the leader of the Soviet Union Nikita Khrushchev. The leaders of the two superpowers of the Cold War era discussed many issues in the relationship between their countries.

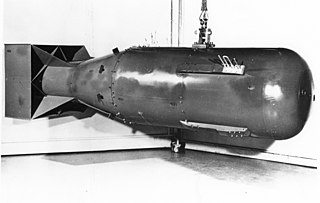

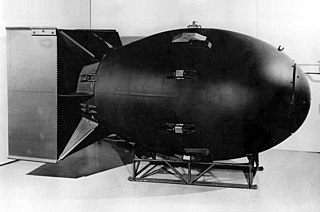

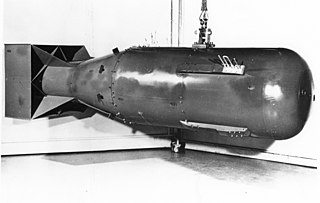

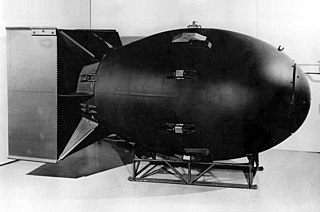

A strategic nuclear weapon (SNW) refers to a nuclear weapon that is designed to be used on targets often in settled territory far from the battlefield as part of a strategic plan, such as military bases, military command centers, arms industries, transportation, economic, and energy infrastructure, and heavily populated areas such as cities and towns, which often contain such targets. It is in contrast to a tactical nuclear weapon, which is designed for use in battle as part of an attack with and often near friendly conventional forces, possibly on contested friendly territory.

John F. Kennedy's tenure as the 35th president of the United States began with his inauguration on January 20, 1961, and ended with his assassination on November 22, 1963. Kennedy, a Democrat from Massachusetts, took office following his narrow victory over Republican incumbent vice president Richard Nixon in the 1960 presidential election. He was succeeded by Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson.

The Berlin Crisis of 1961 was the last major European political and military incident of the Cold War concerning the status of the German capital city, Berlin, and of post–World War II Germany. The crisis culminated in the city's de facto partition with the East German erection of the Berlin Wall.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to the Cold War:

The United States foreign policy during the presidency of John F. Kennedy from 1961 to 1963 included diplomatic and military initiatives in Western Europe, Southeast Asia, and Latin America, all conducted amid considerable Cold War tensions with the Soviet Union and its satellite states in Eastern Europe. Kennedy deployed a new generation of foreign policy experts, dubbed "the best and the brightest". In his inaugural address Kennedy encapsulated his Cold War stance: "Let us never negotiate out of fear. But let us never fear to negotiate".

The United States foreign policy of the Dwight D. Eisenhower administration, from 1953 to 1961, focused on the Cold War with the Soviet Union and its satellites. The United States built up a stockpile of nuclear weapons and nuclear delivery systems to deter military threats and save money while cutting back on expensive Army combat units. A major uprising broke out in Hungary in 1956; the Eisenhower administration did not become directly involved, but condemned the military invasion by the Soviet Union. Eisenhower sought to reach a nuclear test ban treaty with the Soviet Union, but following the 1960 U-2 incident the Kremlin canceled a scheduled summit in Paris.

The Berlin Crisis of 1958–1959 was a crisis over the status of West Berlin during the Cold War. It resulted from efforts by Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev to react strongly against American nuclear warheads located in West Germany, and build up the prestige of the Soviet satellite state of East Germany. American President Dwight D. Eisenhower mobilized NATO opposition. He was strongly supported by German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer, but Great Britain went along reluctantly. There was never any military action. The result was a continuation of the status quo in Berlin, and a move by Eisenhower and Khrushchev toward détente. The Berlin problem had not disappeared, and escalated into a major conflict over building the Berlin Wall in 1961. See Berlin Crisis of 1961.