Poultry are domesticated birds kept by humans for the purpose of harvesting useful animal products such as meat, eggs or feathers. The practice of raising poultry is known as poultry farming. These birds are most typically members of the superorder Galloanserae (fowl), especially the order Galliformes. The term also includes waterfowls of the family Anatidae but does not include wild birds hunted for food known as game or quarry.

The chicken is a large and round short-winged bird, domesticated from the red junglefowl of Southeast Asia around 8,000 years ago. Most chickens are raised for food, providing meat and eggs; others are kept as pets or for cockfighting.

Debeaking, beak trimming, or beak conditioning is the partial removal of the beak of poultry, especially layer hens and turkeys although it may also be performed on quail and ducks. Most commonly, the beak is shortened permanently, although regrowth can occur. The trimmed lower beak is somewhat longer than the upper beak. A similar but separate practice, usually performed by an avian veterinarian or an experienced birdkeeper, involves clipping, filing or sanding the beaks of captive birds for health purposes – in order to correct or temporarily to alleviate overgrowths or deformities and better allow the bird to go about its normal feeding and preening activities. Amongst raptor-keepers, this practice is commonly known as "coping".

The domestic turkey is a large fowl, one of the two species in the genus Meleagris and the same species as the wild turkey. Although turkey domestication was thought to have occurred in central Mesoamerica at least 2,000 years ago, recent research suggests a possible second domestication event in the area that is now the southwestern United States between 200 BC and 500 AD. However, all of the main domestic turkey varieties today descend from the turkey raised in central Mexico that was subsequently imported into Europe by the Spanish in the 16th century.

The Silkie is a breed of chicken named for its atypically fluffy plumage, which is said to feel like silk and satin. The breed has several other unusual qualities, such as black skin and bones, blue earlobes, and five toes on each foot, whereas most chickens have only four. They are often exhibited in poultry shows, and also appear in various colors. In addition to their distinctive physical characteristics, Silkies are well known for their calm and friendly temperament. It is among the most docile of poultry. Hens are also exceptionally broody, and care for young well. Although they are fair layers themselves, laying only about three eggs a week, they are commonly used to hatch eggs from other breeds and bird species due to their broody nature. Silkie chickens have been bred to have a wide variety of colors which include but are not limited to: Black, Blue, Buff, Partridge, Splash, White, Lavender, Paint and Porcelain.

Egg incubation is the process by which an egg, of oviparous (egg-laying) animals, develops an embryo within the egg, after the egg's formation and ovipositional release. Egg incubation is done under favorable environmental conditions, possibly by brooding and hatching the egg.

The Pekin Bantam is a British breed of bantam chicken. It derives from birds brought to Europe from China in the nineteenth century, and is named for the city of Peking where it was believed to have originated. It is a true bantam, with no corresponding large fowl. It is recognised only in the United Kingdom, where the Cochin has no recognised bantam version; like the Cochin, it has heavy feathering to the legs and feet. The Entente Européenne treats the Pekin Bantam as equivalent to the bantam Cochin.

Forced molting, sometimes known as induced molting, is the practice by some poultry industries of artificially provoking a flock to molt simultaneously, typically by withdrawing food for 7–14 days and sometimes also withdrawing water for an extended period. Forced molting is usually implemented when egg-production is naturally decreasing toward the end of the first egg-laying phase. During the forced molt, the birds cease producing eggs for at least two weeks, which allows the bird's reproductive tracts to regress and rejuvenate. After the molt, the hen's egg production rate usually peaks slightly lower than the previous peak, but egg quality is improved. The purpose of forced molting is therefore to increase egg production, egg quality, and profitability of flocks in their second or subsequent laying phases, by not allowing the hen's body the necessary time to rejuvenate during the natural cycle of feather replenishment.

The Campbell is a British breed of domestic duck. It was developed at Uley, in Gloucestershire, England, at the turn of the 20th century; being introduced to the public in 1898 and the Khaki variety in 1901.

Poultry farming is the form of animal husbandry which raises domesticated birds such as chickens, ducks, turkeys and geese to produce meat or eggs for food. Poultry – mostly chickens – are farmed in great numbers. More than 60 billion chickens are killed for consumption annually. Chickens raised for eggs are known as layers, while chickens raised for meat are called broilers.

The Sebright is a British breed of bantam chicken. It is a true bantam – a miniature bird with no corresponding large version – and is one of the oldest recorded British bantam breeds. It is named after Sir John Saunders Sebright, who created it as an ornamental breed by selective breeding in the early nineteenth century.

The Buckeye is an American breed of chicken. It was created in Ohio in the late nineteenth century by Nettie Metcalf. The color of its plumage was intended to resemble the color of the seeds of Aesculus glabra, the Ohio Buckeye plant for which the state is called the 'Buckeye State'.

The Nankin Bantam or Nankin is a British bantam breed of chicken. It is a true bantam, a naturally small breed with no large counterpart from which it was miniaturised. It is of South-east Asian origin, and is among the oldest bantam breeds. It is a yellowish buff colour, and the name is thought to derive from the colour of nankeen cotton from China.

Poultry farming is a part of the United States's agricultural economy.

Urban keeping of chickens as pets, for eggs, meat, or for eating pests is popular in urban and suburban areas. Some people sell the eggs for side income.

Feather pecking is a behavioural problem that occurs most frequently amongst domestic hens reared for egg production, although it does occur in other poultry such as pheasants, turkeys, ducks, broiler chickens and is sometimes seen in farmed ostriches. Feather pecking occurs when one bird repeatedly pecks at the feathers of another. The levels of severity may be recognized as mild and severe. Gentle feather pecking is considered to be a normal investigatory behaviour where the feathers of the recipient are hardly disturbed and therefore does not represent a problem. In severe feather pecking, however, the feathers of the recipient are grasped, pulled at and sometimes removed. This is painful for the receiving bird and can lead to trauma of the skin or bleeding, which in turn can lead to cannibalism and death.

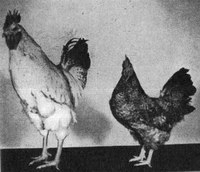

Dwarfism in chickens is an inherited condition found in chickens consisting of a significant delayed growth, resulting in adult individuals with a distinctive small size in comparison with normal specimens of the same breed or population.

Chick sexing is the method of distinguishing the sex of chickens and other hatchlings, usually by a trained person called a chick sexer or chicken sexer. Chicken sexing is practiced mostly by large commercial hatcheries to separate female chicks or "pullets" from the males or "cockerels". The females and a limited number of males kept for meat production are then put on different feeding programs appropriate for their commercial roles.

The broiler industry is the process by which broiler chickens are reared and prepared for meat consumption. Worldwide, in 2005 production was 71,851,000 tonnes. From 1985 to 2005, the broiler industry grew by 158%.

Golden Comet is a cross bred and sex linked chicken gotten from the crossbreeding of a female White Rock or Rhode Island White and a male New Hampshire Red chicken.