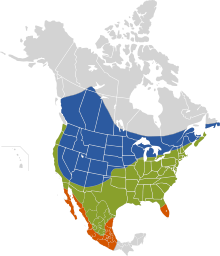

The hooded warbler is a New World warbler. It breeds in eastern North America across the eastern United States and into southernmost Canada (Ontario). It is migratory, wintering in Central America and the West Indies. Hooded warblers are very rare vagrants to western Europe.

The prothonotary warbler is a small songbird of the New World warbler family. It is named for its plumage which resembles the yellow robes once worn by papal clerks in the Roman Catholic Church.

The yellow-wattled lapwing is a lapwing that is endemic to the Indian Subcontinent. It is found mainly on the dry plains of peninsular India and has a sharp call and is capable of fast flight. Although they do not migrate, they are known to make seasonal movements in response to rains. They are dull grey brown with a black cap, yellow legs and a triangular wattle at the base of the beak. Like other lapwings and plovers, they are ground birds and their nest is a mere collection of tiny pebbles within which their well camouflaged eggs are laid. The chicks are nidifugous, leaving the nest shortly after hatching and following their parents to forage for food.

The Asian openbill or Asian openbill stork is a large wading bird in the stork family Ciconiidae. This distinctive stork is found mainly in the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia. It is greyish or white with glossy black wings and tail and the adults have a gap between the arched upper mandible and recurved lower mandible. Young birds are born without this gap which is thought to be an adaptation that aids in the handling of snails, their main prey. Although resident within their range, they make long distance movements in response to weather and food availability.

The Jacobin cuckoo, also pied cuckoo or pied crested cuckoo, is a member of the cuckoo order of birds that is found in Africa and Asia. It is partially migratory and in India, it has been considered a harbinger of the monsoon rains due to the timing of its arrival. It has been associated with a bird in Indian mythology and poetry, known as the chātaka represented as a bird with a beak on its head that waits for rains to quench its thirst.

Brood parasitism is a subclass of parasitism and phenomenon and behavioural pattern of certain animals, brood parasites, that rely on others to raise their young. The strategy appears among birds, insects and fish. The brood parasite manipulates a host, either of the same or of another species, to raise its young as if it were its own, usually using egg mimicry, with eggs that resemble the host's.

The black-naped monarch or black-naped blue flycatcher is a slim and agile passerine bird belonging to the family of monarch flycatchers found in southern and south-eastern Asia. They are sexually dimorphic, with the male having a distinctive black patch on the back of the head and a narrow black half collar ("necklace"), while the female is duller with olive brown wings and lacking the black markings on the head. They have a call that is similar to that of the Asian paradise flycatcher, and in tropical forest habitats, pairs may join mixed-species foraging flocks. Populations differ slightly in plumage colour and sizes.

The brown booby is a large seabird of the booby family Sulidae, of which it is perhaps the most common and widespread species. It has a pantropical range, which overlaps with that of other booby species. The gregarious brown booby commutes and forages at low height over inshore waters. Flocks plunge-dive to take small fish, especially when these are driven near the surface by their predators. They nest only on the ground, and roost on solid objects rather than the water surface.

The diederik cuckoo, formerly dideric cuckoo or didric cuckoo is a member of the cuckoo order of birds, the Cuculiformes, which also includes the roadrunners and the anis.

Cowbirds are birds belonging to the genus Molothrus in the family Icteridae. They are of New World origin, and are obligate brood parasites, laying their eggs in the nests of other species.

The white-lined tanager is a medium-sized passerine bird in the tanager family Thraupidae. It is a resident breeder from Costa Rica south to northern Argentina and on the islands of Trinidad and Tobago.

The giant cowbird is a large passerine bird in the New World family Icteridae. It breeds from southern Mexico south to northern Argentina, and on Trinidad and Tobago. It may have relatively recently colonised the latter island. It is a brood parasite and lays its eggs in the nests of other birds.

The shiny cowbird is a passerine bird in the New World family Icteridae. It breeds in most of South America except for dense forests and areas of high altitude such as mountains. Since 1900 the shiny cowbird's range has shifted northward, and it was recorded in the Caribbean islands as well as the United States, where it is found breeding in southern Florida. It is a bird associated with open habitats, including disturbed land from agriculture and deforestation.

The greater ani is a bird in the cuckoo family. It is sometimes referred to as the black cuckoo. It is found through tropical South America south to northern Argentina.

The pied water tyrant is a small passerine bird in the tyrant flycatcher family. It breeds in tropical South America from Panama and Trinidad south to Bolivia.

The southern bald ibis is a large bird found in open grassland or semi-desert in the mountains of southern Africa. Taxonomically, it is most closely related to its counterpart in the northern regions of Africa, the waldrapp. As a species, it has a very restricted homerange, limited to the southern tips of South Africa in highland and mountainous regions.

Horsfield's bronze cuckoo is a small cuckoo in the family Cuculidae. Its size averages 22g and is distinguished by its green and bronze iridescent colouring on its back and incomplete brown barring from neck to tail. Horsfield's bronze cuckoo can be destiguished from other bronze cuckoos by its white eyebrow and brown eye stripe. The Horsfield's bronze cuckoo is common throughout Australia preferring the drier open woodlands away from forested areas.

The screaming cowbird is an obligate brood parasite belonging to the family Icteridae and is found in South America. It is also known commonly as the short billed cowbird.

Egg tossing or egg destruction is a behavior observed in some species of birds where one individual removes an egg from the communal nest. This is related to infanticide, where parents kill their own or other's offspring. Egg tossing is observed in avian species, most commonly females, who are involved with cooperative breeding or brood parasitism. Among colonial non-co-nesting birds, egg-tossing is observed to be performed by an individual of the same species, and, in the case of brood parasites, this behavior is done by either the same or different species. The behavior of egg tossing offers its advantages and disadvantages to both the actor and recipient.