Germany

The postwar years in Germany brought new challenges, including an ultimately unknowable number of illegitimate children born from unions between occupying Black French, Moroccan, Algerian, and Black American soldiers and native German women. [9] Often the military discouraged fraternization with the locals and any proposed marriages. As an occupying power, the United States military discouraged its forces from fraternizing with Germans. Under any circumstances, soldiers had to get permission of commanding officers in order to marry overseas. As inter-racial marriages were illegal in most of the United States in the era, commanding officers of the U.S. soldiers forced many such couples to split up, or at least prevented their marriages.

Post-World War I

The German attitude toward Black and German biracial children developed shortly after the first world war. These biracial children totaled to approximately 600, and were referred to as mischlingskinder or "Rhineland Bastards." Although all mischlingskinder were racially persecuted, the kind of external response the children received was dependent on the paternity of the child. Children born from solely African paternity in 1918-1935 were deemed less socially acceptable and more disease-ridden than mischlingskinder born from African-American fathers in 1945–1952. [9] They had become symbols of Germany's defeat and during the Third Reich, some had been placed in concentration camps or may have been murdered, though that was not proven. [10]

During World War II and Post-World War II

During World War II, Germany sought to differentiate the Mischlingskinder from the accepted, traditional German race through segregation, forced sterilization, and routine physical examination in order to maintain a pure German ancestral line.

Postwar West German law on illegitimate children was complicated, and made even more so when the father was American. Ultimately, they were wards of the state, but the actual responsibility of the family in which they lived if it had a male present. The mother had no rights in the matter and could not be the legal guardian. That designation and financial responsibility fell to the father or to whomever the mother was married, unless he could prove that the child was not his, which was easily accomplished in the case of biracial children. American soldiers and personnel were excluded from responsibility under the law until 1950, when the U.S. agreed that Germany could have jurisdiction over American soldiers. [11]

Orphanages and foster parents were paid small stipends to care for abandoned children. [12] After losing their American partners when soldiers were reassigned out of Germany, many single German mothers often had difficulty finding support for their children in the postwar nation. There was discrimination against blacks, as they were identified with the resented occupying forces. Still, a 1951 article in Jet noted that most mothers did not give up their "brown babies." White German families who accepted their mischlingskinder were not received well by doctors and anthropologists, their love for their child was seen as awkward, "monkey love." [9] Some Germans fostered or adopted such children; one German woman established a home for thirty "brown babies." [12]

In the decade after the end of the war, numerous illegitimate mixed-race children were put up for adoption. Some were placed with African-American military families in Germany and the United States. [13] By 1968, Americans had adopted about 7,000 "brown babies." [13] Many of the "brown babies" did not learn of their ethnic German ancestry until they reached adulthood. [14] African American newspapers, which had been vocal about equality in the military during the course of the war, took up the cause of the German and English Brown Babies. The Pittsburgh Courier , in particular, was aggressive in reporting on "Brown Babies turned into sideshow attractions," in the countries in which they had been born, and eventually warned of a possible genocide if they were not protected in Germany.

These international orphans ... in the European Command of the American occupation forces ... are being given away, abandoned, killed because their mothers cannot care for them. And there are 1,435 recorded births (unverified) in the Munich (Germany) area alone.

— William G. Nunn, Pittsburgh Courier, 1948, [15]

The article advocated American adoption of each of the children and began to name and locate them specifically for its African American readership.

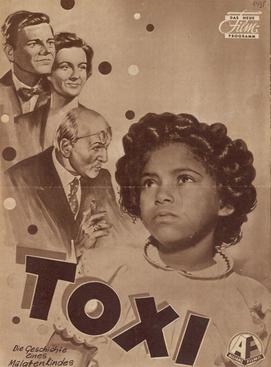

A genocide did not occur, but Blackness and German-ness were seen as exclusive entities in early 1950s Germany. and in the 1950s German attitudes about the children began to evolve away from the racism of World War II toward a less hostile society. A popular culture acknowledgment of the issues was the 1952 feature film Toxi . Its title role was played by Elfie Fiegert, an actress who was herself one of the Mischlingskinder of post-World War II. Toxi tells the story of a young mischlingskinder girl taken in by a modern and multigenerational German family that represented the various beliefs and contradictions of postwar German society. Toxi served as the characterization for Afro-German children who, according to the film, often suffered homelessness and neglect. Although the film pulls on the heartstrings of the audience and prompts sympathy for Black occupation children, the film at its core is racist and promotes tolerance of Blackness rather than integration [16]

The children were not always well treated and often discriminated against. In 1952, a World Brotherhood conference was convened among academics, policy makers and media in Wiesbaden to consider the situation faced by the children and declare that it was incumbent on German society to treat them as equals and to support them in the gaining of secure futures. [17] The conference was in part derived from the perceived irony that a defeated, racist Germany had been occupied by a country that was also racially dangerous, and that the German children would be better off if they stayed in the country in which they had been born.

Eventually, many of the German Brown Babies adopted to America began to search for both their parents. Some have returned to Germany to meet their mothers, if they could trace them. Since the late 20th century, there has been new interest in their stories as part of continuing review of the war and postwar years.