Cetacea is an infraorder of aquatic mammals belonging to the order Artiodactyla that includes whales, dolphins, and porpoises. Key characteristics are their fully aquatic lifestyle, streamlined body shape, often large size and exclusively carnivorous diet. They propel themselves through the water with powerful up-and-down movement of their tail which ends in a paddle-like fluke, using their flipper-shaped forelimbs to maneuver.

Whales are a widely distributed and diverse group of fully aquatic placental marine mammals. As an informal and colloquial grouping, they correspond to large members of the infraorder Cetacea, i.e. all cetaceans apart from dolphins and porpoises. Dolphins and porpoises may be considered whales from a formal, cladistic perspective. Whales, dolphins and porpoises belong to the order Cetartiodactyla, which consists of even-toed ungulates. Their closest non-cetacean living relatives are the hippopotamuses, from which they and other cetaceans diverged about 54 million years ago. The two parvorders of whales, baleen whales (Mysticeti) and toothed whales (Odontoceti), are thought to have had their last common ancestor around 34 million years ago. Mysticetes include four extant (living) families: Balaenopteridae, Balaenidae, Cetotheriidae, and Eschrichtiidae. Odontocetes include the Monodontidae, Physeteridae, Kogiidae, and Ziphiidae, as well as the six families of dolphins and porpoises which are not considered whales in the informal sense.

Rorquals are the largest group of baleen whales, comprising the family Balaenopteridae, which contains ten extant species in three genera. They include the largest known animal that has ever lived, the blue whale, which can reach 180 tonnes, and the fin whale, which reaches 120 tonnes ; even the smallest of the group, the northern minke whale, reaches 9 tonnes.

The fin whale, also known as the finback whale or common rorqual, is a species of baleen whale and the second-longest cetacean after the blue whale. The biggest individual reportedly measured 26 m (85 ft) in length, with a maximum recorded weight of 77,000–81,000 kg (170,000–179,000 lb). The fin whale's body is long, slender and brownish-gray in color, with a paler underside to appear less conspicuous from below (countershading).

Bryde's whale, or the Bryde's whale complex, putatively comprises three species of rorqual and maybe four. The "complex" means the number and classification remains unclear because of a lack of definitive information and research. The common Bryde's whale is a larger form that occurs worldwide in warm temperate and tropical waters, and the Sittang or Eden's whale is a smaller form that may be restricted to the Indo-Pacific. Also, a smaller, coastal form of B. brydei is found off southern Africa, and perhaps another form in the Indo-Pacific differs in skull morphology, tentatively referred to as the Indo-Pacific Bryde's whale. The recently described Omura's whale, was formerly thought to be a pygmy form of Bryde's, but is now recognized as a distinct species. Rice's whale, which makes its home solely in the Gulf of Mexico, was once considered a distinct population of Bryde's whale, but in 2021 it was described as a separate species.

Baleen whales, also known as whalebone whales, are marine mammals of the parvorder Mysticeti in the infraorder Cetacea which use keratinaceous baleen plates in their mouths to sieve planktonic creatures from the water. Mysticeti comprises the families Balaenidae, Balaenopteridae (rorquals), Eschrichtiidae and Cetotheriidae. There are currently 16 species of baleen whales. While cetaceans were historically thought to have descended from mesonychians, molecular evidence instead supports them as a clade of even-toed ungulates (Artiodactyla). Baleen whales split from toothed whales (Odontoceti) around 34 million years ago.

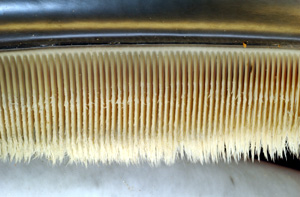

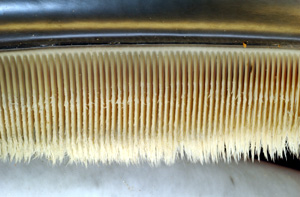

Baleen is a filter-feeding system inside the mouths of baleen whales. To use baleen, the whale first opens its mouth underwater to take in water. The whale then pushes the water out, and animals such as krill are filtered by the baleen and remain as a food source for the whale. Baleen is similar to bristles and consists of keratin, the same substance found in human fingernails, skin and hair. Baleen is a skin derivative. Some whales, such as the bowhead whale, have longer baleen than others. Other whales, such as the gray whale, only use one side of their baleen. These baleen bristles are arranged in plates across the upper jaw of whales.

The humpback whale is a species of baleen whale. It is a rorqual and is the only species in the genus Megaptera. Adults range in length from 14–17 m (46–56 ft) and weigh up to 40 metric tons. The humpback has a distinctive body shape, with long pectoral fins and tubercles on its head. It is known for breaching and other distinctive surface behaviors, making it popular with whale watchers. Males produce a complex song typically lasting 4 to 33 minutes.

The minke whale, or lesser rorqual, is a species complex of baleen whale. The two species of minke whale are the common minke whale and the Antarctic minke whale. The minke whale was first described by the Danish naturalist Otto Fabricius in 1780, who assumed it must be an already known species and assigned his specimen to Balaena rostrata, a name given to the northern bottlenose whale by Otto Friedrich Müller in 1776. In 1804, Bernard Germain de Lacépède described a juvenile specimen of Balaenoptera acuto-rostrata. The name is a partial translation of Norwegian minkehval, possibly after a Norwegian whaler named Meincke, who mistook a northern minke whale for a blue whale.

Whale watching is the practice of observing whales and dolphins (cetaceans) in their natural habitat. Whale watching is mostly a recreational activity, but it can also serve scientific and/or educational purposes. A study prepared for International Fund for Animal Welfare in 2009 estimated that 13 million people went whale watching globally in 2008. Whale watching generates $2.1 billion per annum in tourism revenue worldwide, employing around 13,000 workers. The size and rapid growth of the industry has led to complex and continuing debates with the whaling industry about the best use of whales as a natural resource.

The sei whale is a baleen whale. It is one of ten rorqual species, and the third-largest member after the blue and fin whales. They can grow up to 19.5 m (64 ft) in length and weigh as much as 28 t. Two subspecies are recognized: B. b. borealis and B. b. schlegelii. The whale's ventral surface has sporadic markings ranging from light grey to white, and its body is usually dark steel grey in colour. It is among the fastest of all cetaceans, and can reach speeds of up to 50 km/h (31 mph) over short distances.

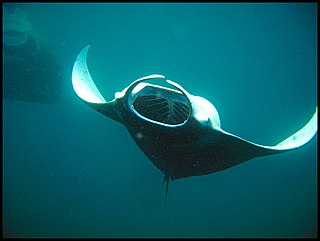

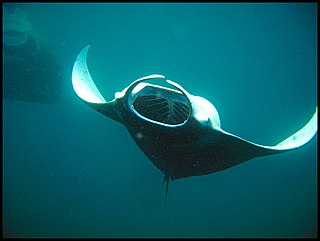

Filter feeders are a sub-group of suspension feeding animals that feed by straining suspended matter and food particles from water, typically by passing the water over a specialized filtering structure. Some animals that use this method of feeding are clams, krill, sponges, baleen whales, and many fish. Some birds, such as flamingos and certain species of duck, are also filter feeders. Filter feeders can play an important role in clarifying water, and are therefore considered ecosystem engineers. They are also important in bioaccumulation and, as a result, as indicator organisms.

Cetacean surfacing behaviour is a grouping of movement types that cetaceans make at the water's surface in addition to breathing. Cetaceans have developed and use surface behaviours for many functions such as display, feeding and communication. All regularly observed members of the order Cetacea, including whales, dolphins and porpoises, show a range of surfacing behaviours.

The Japanese flying squid, Japanese common squid or Pacific flying squid, scientific name Todarodes pacificus, is a squid of the family Ommastrephidae. This animal lives in the northern Pacific Ocean, in the area surrounding Japan, along the entire coast of China up to Russia, then spreading across the Bering Strait east towards the southern coast of Alaska and Canada. They tend to cluster around the central region of Vietnam.

The Hawaiian Islands Humpback Whale National Marine Sanctuary is one of the world's most important whale habitats, hosting thousands of humpbacks each winter.

A bait ball, or baitball, occurs when small fish swarm in a tightly packed spherical formation about a common centre. It is a last-ditch defensive measure adopted by small schooling fish when they are threatened by predators. Small schooling fish are eaten by many types of predators, and for this reason they are called bait fish or forage fish.

Aquatic feeding mechanisms face a special difficulty as compared to feeding on land, because the density of water is about the same as that of the prey, so the prey tends to be pushed away when the mouth is closed. This problem was first identified by Robert McNeill Alexander. As a result, underwater predators, especially bony fish, have evolved a number of specialized feeding mechanisms, such as filter feeding, ram feeding, suction feeding, protrusion, and pivot feeding.

A planktivore is an aquatic organism that feeds on planktonic food, including zooplankton and phytoplankton. Planktivorous organisms encompass a range of some of the planet's smallest to largest multicellular animals in both the present day and in the past billion years; basking sharks and copepods are just two examples of giant and microscopic organisms that feed upon plankton.

The physiology of underwater diving is the physiological adaptations to diving of air-breathing vertebrates that have returned to the ocean from terrestrial lineages. They are a diverse group that include sea snakes, sea turtles, the marine iguana, saltwater crocodiles, penguins, pinnipeds, cetaceans, sea otters, manatees and dugongs. All known diving vertebrates dive to feed, and the extent of the diving in terms of depth and duration are influenced by feeding strategies, but also, in some cases, with predator avoidance. Diving behaviour is inextricably linked with the physiological adaptations for diving and often the behaviour leads to an investigation of the physiology that makes the behaviour possible, so they are considered together where possible. Most diving vertebrates make relatively short shallow dives. Sea snakes, crocodiles, and marine iguanas only dive in inshore waters and seldom dive deeper than 10 meters. Some of these groups can make much deeper and longer dives. Emperor penguins regularly dive to depths of 400 to 500 meters for 4 to 5 minutes, often dive for 8 to 12 minutes, and have a maximum endurance of about 22 minutes. Elephant seals stay at sea for between 2 and 8 months and dive continuously, spending 90% of their time underwater and averaging 20 minutes per dive with less than 3 minutes at the surface between dives. Their maximum dive duration is about 2 hours and they routinely feed at depths between 300 and 600 meters, though they can exceed depths of 1,600 meters. Beaked whales have been found to routinely dive to forage at depths between 835 and 1,070 meters, and remain submerged for about 50 minutes. Their maximum recorded depth is 1,888 meters, and the maximum duration is 85 minutes.

Rice's whale, also known as the Gulf of Mexico whale, is a species of baleen whale endemic to the northern Gulf of Mexico. Initially identified as a subpopulation of the Bryde's whale, genetic and skeletal studies found it to be a distinct species by 2021. In outward appearance, it is virtually identical to the Bryde's whale. Its body is streamlined and sleek, with a uniformly dark charcoal gray dorsal and pale to pinkish underside. A diagnostic feature often used by field scientists to distinguish Rice's whales from whales other than the Bryde's whale is the three prominent ridges that line the top of its head. The species can be distinguished from the Bryde's whale by the shape of the nasal bones, which have wider gaps due to a unique wrapping by the frontal bones, its unique vocal repertoire, and genetic differences.