The United States of America has separate federal, state, and local governments with taxes imposed at each of these levels. Taxes are levied on income, payroll, property, sales, capital gains, dividends, imports, estates and gifts, as well as various fees. In 2020, taxes collected by federal, state, and local governments amounted to 25.5% of GDP, below the OECD average of 33.5% of GDP. The United States had the seventh-lowest tax revenue-to-GDP ratio among OECD countries in 2020, with a higher ratio than Mexico, Colombia, Chile, Ireland, Costa Rica, and Turkey.

A capital gains tax (CGT) is the tax on profits realized on the sale of a non-inventory asset. The most common capital gains are realized from the sale of stocks, bonds, precious metals, real estate, and property.

Passive income is unearned income that is acquired automatically with minimal labor to earn or maintain. It is often combined with another source of income, such as a side job. In the United States, the IRS divides income into three categories: active income, passive income, and portfolio income. Passive income, as an acquired income, is the result of capital growth or is related to the tax deduction mechanism, and is taxable.

Nonrecourse debt or a nonrecourse loan is a secured loan (debt) that is secured by a pledge of collateral, typically real property, but for which the borrower is not personally liable. If the borrower defaults, the lender can seize and sell the collateral, but if the collateral sells for less than the debt, the lender cannot seek that deficiency balance from the borrower—its recovery is limited only to the value of the collateral. Thus, nonrecourse debt is typically limited to 50% or 60% loan-to-value ratios, so that the property itself provides "overcollateralization" of the loan.

For households and individuals, gross income is the sum of all wages, salaries, profits, interest payments, rents, and other forms of earnings, before any deductions or taxes. It is opposed to net income, defined as the gross income minus taxes and other deductions.

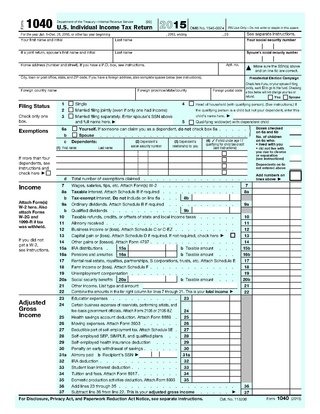

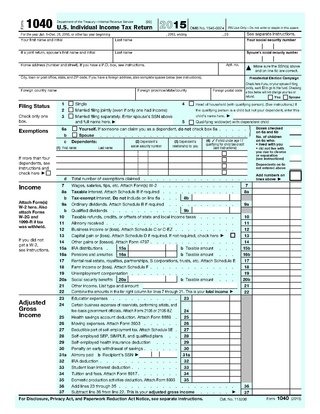

Income taxes in the United States are imposed by the federal government, and most states. The income taxes are determined by applying a tax rate, which may increase as income increases, to taxable income, which is the total income less allowable deductions. Income is broadly defined. Individuals and corporations are directly taxable, and estates and trusts may be taxable on undistributed income. Partnerships are not taxed, but their partners are taxed on their shares of partnership income. Residents and citizens are taxed on worldwide income, while nonresidents are taxed only on income within the jurisdiction. Several types of credits reduce tax, and some types of credits may exceed tax before credits. An alternative tax applies at the federal and some state levels.

1231 Property is a category of property defined in section 1231 of the U.S. Internal Revenue Code. 1231 property includes depreciable property and real property used in a trade or business and held for more than one year. Some types of livestock, coal, timber and domestic iron ore are also included. It does not include: inventory; property held for sale in the ordinary course of business; artistic creations held by their creator; or, government publications.

Section 61 of the Internal Revenue Code defines "gross income," the starting point for determining which items of income are taxable for federal income tax purposes in the United States. Section 61 states that "[e]xcept as otherwise provided in this subtitle, gross income means all income from whatever source derived [. .. ]". The United States Supreme Court has interpreted this to mean that Congress intended to express its full power to tax incomes to the extent that such taxation is permitted under Article I, Section 8, Clause 1 of the Constitution of the United States and under the Constitution's Sixteenth Amendment.

Under Section 1031 of the United States Internal Revenue Code, a taxpayer may defer recognition of capital gains and related federal income tax liability on the exchange of certain types of property, a process known as a 1031 exchange. In 1979, this treatment was expanded by the courts to include non-simultaneous sale and purchase of real estate, a process sometimes called a Starker exchange.

In civil and property law, hotchpot is the blending, combining or offsetting of property to ensure equality of a later division of property.

In the United States of America, individuals and corporations pay U.S. federal income tax on the net total of all their capital gains. The tax rate depends on both the investor's tax bracket and the amount of time the investment was held. Short-term capital gains are taxed at the investor's ordinary income tax rate and are defined as investments held for a year or less before being sold. Long-term capital gains, on dispositions of assets held for more than one year, are taxed at a lower rate.

Taxpayers in the United States may have tax consequences when debt is cancelled. This is commonly known as cancellation-of-debt (COD) income. According to the Internal Revenue Code, the discharge of indebtedness must be included in a taxpayer's gross income. There are exceptions to this rule, however, so a careful examination of one's COD income is important to determine any potential tax consequences.

Depreciation recapture is the USA Internal Revenue Service (IRS) procedure for collecting income tax on a gain realized by a taxpayer when the taxpayer disposes of an asset that had previously provided an offset to ordinary income for the taxpayer through depreciation. In other words, because the IRS allows a taxpayer to deduct the depreciation of an asset from the taxpayer's ordinary income, the taxpayer has to report any gain from the disposal of the asset as ordinary income, not as a capital gain.

In United States income tax law, an installment sale is generally a "disposition of property where at least 1 loan payment is to be received after the close of the taxable year in which the disposition occurs." The term "installment sale" does not include, however, a "dealer disposition" or, generally, a sale of inventory. The installment method of accounting provides an exception to the general principles of income recognition by allowing a taxpayer to defer the inclusion of income of amounts that are to be received from the disposition of certain types of property until payment in cash or cash equivalents is received. The installment method defers the recognition of income when compared with both the cash and accrual methods of accounting. Under the cash method, the taxpayer would recognize the income when it is received, including the entire sum paid in the form of a negotiable note. The deferral advantages of the installment method are the most pronounced when comparing to the accrual method, under which a taxpayer must recognize income as soon as he or she has a right to the income.

Arkansas Best Corporation v. Commissioner, 485 U.S. 212 (1988), is a United States Supreme Court decision that helps taxpayers classify whether or not the sale of an asset is an ordinary or capital gain or loss for income tax purposes.

A like-kind exchange under United States tax law, also known as a 1031 exchange, is a transaction or series of transactions that allows for the disposal of an asset and the acquisition of another replacement asset without generating a current tax liability from the sale of the first asset. A like-kind exchange can involve the exchange of one business for another business, one real estate investment property for another real estate investment property, livestock for qualifying livestock, and exchanges of other qualifying assets. Like-kind exchanges have been characterized as tax breaks or "tax loopholes".

In Kenan v. Commissioner, 114 F. 2d 217, the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit provided a broad definition of the term "sale or exchange." The Kenan court reviewed the Commissioner's finding of a $367,687.12 deficiency in the income taxes of the trustees. The trustees or taxpayers contended "that the delivery of the securities of the trust estate to the legatee was a donative disposition of property. .. and that no gain was thereby realized." The court pointed out that "the trustees had the power to determine whether the claim should be satisfied [in cash or securities]." Thus, "[i]f it were satisfied by a cash payment securities might have been sold on which. .. a taxable gain would necessarily have been realized." The court found that "[t]he word 'exchange' does not necessarily have the connotation of a bilateral agreement which may be said to attach to the word 'sale.'" The court then held that the trustees or taxpayers had realized a gain when they used the securities to satisfy the claim on the estate.

Surrogatum is a thing put in the place of another or a substitute. The Surrogatum Principle pertains to a Canadian income tax principle involving a person who suffers harm caused by another and may seek compensation for (a) loss of income, (b) expenses incurred, (c) property destroyed, or (d) personal injury, as well as punitive damages, under the surrogatum principle, the tax consequences of a damage or settlement payment depend on the tax treatment of the item for which the payment is intended to substitute.

Tax protesters in the United States advance a number of constitutional arguments asserting that the imposition, assessment and collection of the federal income tax violates the United States Constitution. These kinds of arguments, though related to, are distinguished from statutory and administrative arguments, which presuppose the constitutionality of the income tax, as well as from general conspiracy arguments, which are based upon the proposition that the three branches of the federal government are involved together in a deliberate, on-going campaign of deception for the purpose of defrauding individuals or entities of their wealth or profits. Although constitutional challenges to U.S. tax laws are frequently directed towards the validity and effect of the Sixteenth Amendment, assertions that the income tax violates various other provisions of the Constitution have been made as well.

Corn Products Refining Company v. Commissioner, 350 U.S. 46 (1955), is a United States Supreme Court decision that helps taxpayers classify whether or not the disposition of a commodity futures contract by a business of raw materials as part of its hedging of business risk is an ordinary or capital gain or loss for income tax purposes.