The politics of Finland take place within the framework of a parliamentary representative democracy. Finland is a republic whose head of state is President Alexander Stubb, who leads the nation's foreign policy and is the supreme commander of the Finnish Defence Forces. Finland's head of government is Prime Minister Petteri Orpo, who leads the nation's executive branch, called the Finnish Government. Legislative power is vested in the Parliament of Finland, and the Government has limited rights to amend or extend legislation. The Constitution of Finland vests power to both the President and Government: the President has veto power over parliamentary decisions, although this power can be overruled by a majority vote in the Parliament.

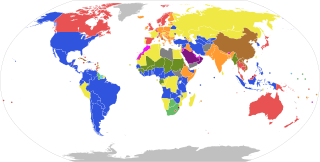

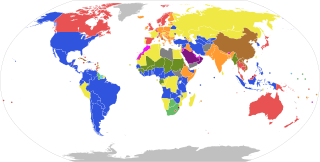

The Westminster system, or Westminster model, is a type of parliamentary government that incorporates a series of procedures for operating a legislature, first developed in England. Key aspects of the system include an executive branch made up of members of the legislature, and that is responsible to the legislature; the presence of parliamentary opposition parties; and a ceremonial head of state who is separate from the head of government. The term derives from the Palace of Westminster, which has been the seat of the Westminster Parliament in England and later the United Kingdom since the 13th century. The Westminster system is often contrasted with the presidential system that originated in the United States, or with the semi-presidential system, based on the government of France.

The president of the Council of Ministers, colloquially and commonly referred to as the prime minister, is the head of the cabinet and the head of government of Poland. The responsibilities and traditions of the office stem from the creation of the contemporary Polish state, and the office is defined in the Constitution of Poland. According to the Constitution, the president nominates and appoints the prime minister, who will then propose the composition of the Cabinet. Fourteen days following their appointment, the prime minister must submit a programme outlining the government's agenda to the Sejm, requiring a vote of confidence. Conflicts stemming from both interest and powers have arisen between the offices of President and Prime Minister in the past.

In a parliamentary or semi-presidential system of government, a reserve power, also known as discretionary power, is a power that may be exercised by the head of state without the approval of another branch or part of the government. Unlike in a presidential system of government, the head of state is generally constrained by the cabinet or the legislature in a parliamentary system, and most reserve powers are usable only in certain exceptional circumstances.

A motion or vote of no confidence is a formal expression by a deliberative body as to whether an officeholder is deemed fit to continue to occupy their office. The no-confidence vote is a defining feature of parliamentary democracy which allows the elected parliament to either affirm their support or force the ousting of the cabinet. Systems differ in whether such a motion may be directed against the prime minister only or against individual cabinet ministers.

The premier of Ontario is the head of government of Ontario. Under the Westminster system, the premier governs with the confidence of a majority the elected Legislative Assembly; as such, the premier typically sits as a member of Provincial Parliament (MPP) and leads the largest party or a coalition of parties. As first minister, the premier selects ministers to form the Executive Council, and serves as its chair. Constitutionally, the Crown exercises executive power on the advice of the Executive Council, which is collectively responsible to the legislature.

The Cabinet of New Zealand is the New Zealand Government's body of senior ministers, accountable to the New Zealand Parliament. Cabinet meetings, chaired by the prime minister, occur once a week; in them, vital issues are discussed and government policy is formulated. Cabinet is also composed of a number of committees focused on specific areas of governance and policy. Though not established by any statute, Cabinet wields significant power within the New Zealand political system, with nearly all government bills it introduces in Parliament being enacted.

The Executive Council of New Zealand is the full group of "responsible advisers" to the governor-general, who advise on state and constitutional affairs. All government ministers must be appointed as executive councillors before they are appointed as ministers; therefore all members of Cabinet are also executive councillors. The governor-general signs a warrant of appointment for each member of the Executive Council, and separate warrants for each ministerial portfolio.

The Cabinet of Australia, also known as the Federal Cabinet, is the chief decision-making body of the Australian government. The cabinet is appointed by the prime minister of Australia and is composed of senior government ministers who head the executive departments and ministries of the federal government. The cabinet is separate to the federal Department of the Prime Ministers and Cabinet.

The cabinet of the Netherlands is the main executive body of the Netherlands. The latest cabinet of the Netherlands is the Fourth Rutte cabinet, which has been in power since 10 January 2022, until 7 July 2023. It is headed by Prime Minister Mark Rutte.

In Westminster-style governments, individual ministerial responsibility is a constitutional convention that a cabinet minister bears the ultimate responsibility for the actions of their ministry or department. Individual ministerial responsibility is not the same as cabinet collective responsibility, which states members of the cabinet must approve publicly of its collective decisions or resign. This means that a Parliamentary motion for a vote of no confidence is not in order should the actions of an organ of government fail in the proper discharge of its responsibilities. Where there is ministerial responsibility, the accountable minister is expected to take the blame and ultimately resign, but the majority or coalition within parliament of which the minister is part, is not held to be answerable for that minister's failure.

The politics of Australia operates under the written Australian Constitution, which sets out Australia as a constitutional monarchy, governed via a parliamentary democracy in the Westminster tradition. Australia is also a federation, where power is divided between the federal government and the states and territories. The monarch, currently King Charles III, is the head of state and is represented locally by the Governor-General of Australia, while the head of government is the Prime Minister of Australia, currently Anthony Albanese.

The New Zealand Government is the central government through which political authority is exercised in New Zealand. As in most other parliamentary democracies, the term "Government" refers chiefly to the executive branch, and more specifically to the collective ministry directing the executive. Based on the principle of responsible government, it operates within the framework that "the [King] reigns, but the government rules, so long as it has the support of the House of Representatives". The Cabinet Manual describes the main laws, rules and conventions affecting the conduct and operation of the Government.

Article 49 of the French Constitution is an article of the French Constitution, the fundamental law of the Fifth French Republic. It sets out and structures the political responsibility of the government towards the parliament. It is part of Title V: "On relations between the parliament and the government", and with the intention of maintaining the stability of the French executive the section provides legislative alternatives to the parliament. It was written into the constitution to counter the perceived weakness of the Fourth Republic, such as "deadlock" and successive rapid government takeovers, by giving the government the ability to pass bills without the approbation of the parliament, possible under Section 3 of Article 49.

The Council of State, is a formal body composed of the most senior government ministers chosen by the Prime Minister, and functions as the collective decision-making organ constituting the executive branch of the Kingdom. The council simultaneously plays the role of privy council as well as government Cabinet.

His Majesty's Government is the central executive authority of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. The government is led by the prime minister who selects all the other ministers. The country has had a Conservative-led government since 2010, with successive prime ministers being the then-leader of the Conservative Party. The prime minister and their most senior ministers belong to the supreme decision-making committee, known as the Cabinet.

A cabinet is a group of members usually from the executive branch. Cabinets are typically the body responsible for the day-to-day management of the government and response to sudden events, whereas the legislative and judicial branches work in a measured pace, in sessions according to lengthy procedures.

The United Kingdom has an uncodified constitution. The constitution consists of legislation, common law, Crown prerogative and constitutional conventions. Conventions may be written or unwritten. They are principles of behaviour which are not legally enforceable, but form part of the constitution by being enforced on a political, professional or personal level. Written conventions can be found in the Ministerial Code, Cabinet Manual, Guide to Judicial Conduct, Erskine May and even legislation. Unwritten conventions exist by virtue of long-practice or may be referenced in other documents such as the Lascelles Principles.

Semi-parliamentary system can refer to one of the following:

The Cabinet Manual is a government document in New Zealand which outlines the main laws, rules and constitutional conventions affecting the operation of the New Zealand Government. It has been described as providing "comprehensive, cohesive and clear advice on a number of key aspects of executive action. It is publicly available, and broadly accepted by a wide range of actors in NZ politics: politicians across the spectrum, officials, academics and the public."