Corvidae is a cosmopolitan family of oscine passerine birds that contains the crows, ravens, rooks, magpies, jackdaws, jays, treepies, choughs, and nutcrackers. In colloquial English, they are known as the crow family or corvids. Currently, 135 species are included in this family. The genus Corvus containing 47 species makes up over a third of the entire family. Corvids (ravens) are the largest passerines.

The carrion crow is a passerine bird of the family Corvidae and the genus Corvus which is native to western Europe and the eastern Palearctic.

The western jackdaw, also known as the Eurasian jackdaw, the European jackdaw, or simply the jackdaw, is a passerine bird in the crow family. Found across Europe, western Asia and North Africa; it is mostly resident, although northern and eastern populations migrate south in the winter. Four subspecies are recognised, which differ mainly in the colouration of the plumage on the head and nape. Linnaeus first described it formally, giving it the name Corvus monedula. The common name derives from the word jack, denoting "small", and daw, a less common synonym for "jackdaw", and the native English name for the bird.

The Eurasian jay is a species of passerine bird in the crow family Corvidae. It has pinkish brown plumage with a black stripe on each side of a whitish throat, a bright blue panel on the upper wing and a black tail. The Eurasian jay is a woodland bird that occurs over a vast region from western Europe and north-west Africa to the Indian subcontinent and further to the eastern seaboard of Asia and down into south-east Asia. Across this vast range, several distinct racial forms have evolved which look different from each other, especially when comparing forms at the extremes of its range.

The blue jay is a passerine bird in the family Corvidae, native to eastern North America. It lives in most of the eastern and central United States; some eastern populations may be migratory. Resident populations are also in Newfoundland, Canada; breeding populations are found across southern Canada. It breeds in both deciduous and coniferous forests, and is common in residential areas. Its coloration is predominantly blue, with a white chest and underparts, and a blue crest; it has a black, U-shaped collar around its neck and a black border behind the crest. Males and females are similar in size and plumage, and plumage does not vary throughout the year. Four subspecies have been recognized.

The passerine birds of the genus Aphelocoma include the scrub jays and their relatives. They are New World jays found in Mexico, western Central America and the western United States, with an outlying population in Florida. This genus belongs to the group of New World jays–possibly a distinct subfamily–which is not closely related to other jays, magpies or treepies. They live in open pine-oak forests, chaparral, and mixed evergreen forests.

The rufous treepie is a treepie, native to the Indian Subcontinent and adjoining parts of Southeast Asia. It is a member of the crow family, Corvidae. It is long tailed and has loud musical calls making it very conspicuous. It is found commonly in open scrub, agricultural areas, forests as well as urban gardens. Like other corvids it is very adaptable, omnivorous and opportunistic in feeding.

The common raven is a large all-black passerine bird. It is the most widely distributed of all corvids, found across the Northern Hemisphere. It is a raven known by many names at the subspecies level; there are at least eight subspecies with little variation in appearance, although recent research has demonstrated significant genetic differences among populations from various regions. It is one of the two largest corvids, alongside the thick-billed raven, and is possibly the heaviest passerine bird; at maturity, the common raven averages 63 centimetres in length and 1.47 kilograms in mass. Although their typical lifespan is considerably shorter, common ravens can live more than 23 years in the wild. Young birds may travel in flocks but later mate for life, with each mated pair defending a territory.

The island scrub jay, also known as the island jay or Santa Cruz jay, is a bird in the genus, Aphelocoma, which is endemic to Santa Cruz Island off the coast of Southern California. Of the over 500 breeding bird species in the continental U.S. and Canada, it is the only insular endemic landbird species.

The Mexican jay formerly known as the gray-breasted jay, is a New World jay native to the Sierra Madre Oriental, Sierra Madre Occidental, and Central Plateau of Mexico and parts of the southwestern United States. In May 2011, the American Ornithologists' Union voted to split the Mexican jay into two species, one retaining the common name Mexican jay and one called the Transvolcanic jay. The Mexican jay is a medium-sized jay with blue upper parts and pale gray underparts. It resembles the Woodhouse's scrub-jay, but has an unstreaked throat and breast. It feeds largely on acorns and pine nuts, but includes many other plant and animal foods in its diet. It has a cooperative breeding system where the parents are assisted by other birds to raise their young. This is a common species with a wide range and the International Union for Conservation of Nature has rated its conservation status as being of "least concern".

Hoarding or caching in animal behavior is the storage of food in locations hidden from the sight of both conspecifics and members of other species. Most commonly, the function of hoarding or caching is to store food in times of surplus for times when food is less plentiful. However, there is evidence that a certain amount of caching or hoarding is actually undertaken with the aim of ripening the food so stored, and this practice is thus referred to as ‘ripening caching’. The term hoarding is most typically used for rodents, whereas caching is more commonly used in reference to birds, but the behaviors in both animal groups are quite similar.

The difficulty of defining or measuring intelligence in non-human animals makes the subject difficult to study scientifically in birds. In general, birds have relatively large brains compared to their head size. Furthermore, bird brains have two-to-four times the neuron packing density of mammal brains, for higher overall efficiency. The visual and auditory senses are well developed in most species, though the tactile and olfactory senses are well realized only in a few groups. Birds communicate using visual signals as well as through the use of calls and song. The testing of intelligence in birds is therefore usually based on studying responses to sensory stimuli.

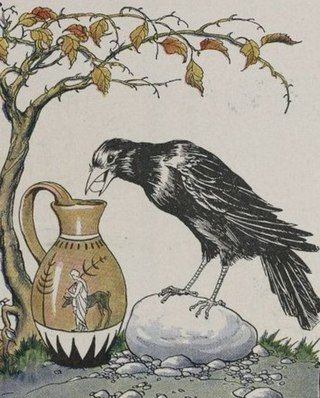

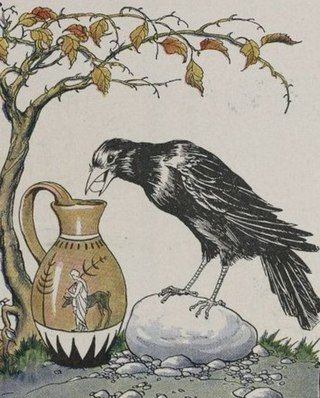

The Crow and the Pitcher is one of Aesop's Fables, numbered 390 in the Perry Index. It relates ancient observation of corvid behaviour that recent scientific studies have confirmed is goal-directed and indicative of causal knowledge rather than simply being due to instrumental conditioning.

The Florida scrub jay is one of the species of scrub jay native to North America. It is the only species of bird endemic to the U.S. state of Florida and one of only 15 species endemic to the continental United States. Because of this, it is keenly sought by birders. It is known to have been present in Florida as a distinct species for at least 2 million years, and is possibly derived from the ancestors of Woodhouse's scrub jay.

The pinyon jay is a species of jay, and is the only member of the genus Gymnorhinus. Native to Western North America, the species ranges from central Oregon to northern Baja California, and eastward as far as western Oklahoma, though wanderers are often sighted beyond this range. It is typically found within foothills, especially where pinyon pines occur.

Episodic-like memory is the memory system in animals that is comparable to human episodic memory. The term was first described by Clayton & Dickinson referring to an animal's ability to encode and retrieve information about 'what' occurred during an episode, 'where' the episode took place, and 'when' the episode happened. This ability in animals is considered 'episodic-like' because there is currently no way of knowing whether or not this form of remembering is accompanied by conscious recollection—a key component of Endel Tulving's original definition of episodic memory.

Woodhouse's scrub jay is a species of scrub jay native to western North America, ranging from southeastern Oregon and southern Idaho to central Mexico. Woodhouse's scrub jay was until recently considered the same species as the California scrub jay, and collectively called the western scrub jay. Prior to that both of them were also considered the same species as the island scrub jay and the Florida scrub jay; the taxon was then called simply the scrub jay. Woodhouse's scrub jay is nonmigratory and can be found in urban areas, where it can become tame and will come to bird feeders. While many refer to scrub jays as "blue jays", the blue jay is a different species of bird entirely. Woodhouse's scrub jay is named for the American naturalist and explorer Samuel Washington Woodhouse.

Nicola Susan Clayton PhD, FRS, FSB, FAPS, C is a British psychologist. She is Professor of Comparative Cognition at the University of Cambridge, Scientist in Residence at Rambert Dance Company, co-founder of 'The Captured Thought', a Fellow of Clare College, Cambridge, where she is Director of Studies in Psychology, and a Fellow of the Royal Society since 2010. Clayton was made Honorary Director of Studies and advisor to the 'China UK Development Centre'(CUDC) in 2018. She has been awarded professorships by Nanjing University, Institute of Technology, China (2018), Beijing University of Language and Culture, China (2019), and Hangzhou Diangi University, China (2019). Clayton was made Director of the Cambridge Centre for the Integration of Science, Technology and Culture (CCISTC) in 2020.

Theory of mind in animals is an extension to non-human animals of the philosophical and psychological concept of theory of mind (ToM), sometimes known as mentalisation or mind-reading. It involves an inquiry into whether non-human animals have the ability to attribute mental states to themselves and others, including recognition that others have mental states that are different from their own. To investigate this issue experimentally, researchers place non-human animals in situations where their resulting behavior can be interpreted as supporting ToM or not.

The evolution of cognition is the process by which life on Earth has gone from organisms with little to no cognitive function to a greatly varying display of cognitive function that we see in organisms today. Animal cognition is largely studied by observing behavior, which makes studying extinct species difficult. The definition of cognition varies by discipline; psychologists tend define cognition by human behaviors, while ethologists have widely varying definitions. Ethological definitions of cognition range from only considering cognition in animals to be behaviors exhibited in humans, while others consider anything action involving a nervous system to be cognitive.