| Cambridge movement | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Civil Rights Movement | |||

| Date | December 1961 – 1964 | ||

| Location | |||

| Caused by |

| ||

| Resulted in |

| ||

| Parties | |||

| |||

| Lead figures | |||

Mayor of Cambridge | |||

The Cambridge movement was an American social movement in Dorchester County, Maryland, led by Gloria Richardson and the Cambridge Nonviolent Action Committee. Protests continued from late 1961 to the summer of 1964. The movement led to the desegregation of all schools, recreational areas, and hospitals in Maryland and the longest period of martial law within the United States since 1877. [1] Many cite it as the birth of the Black Power movement. [2]

Black residents of Cambridge had the right to vote, but they were still discriminated against and lacked economic opportunities. Their homes lacked plumbing, with some even living in "chicken shacks". Since the local hospitals were segregated and only served white people, Black residents had to drive two hours to Baltimore for medical care. [3] They experienced the highest rates of unemployment. The Black unemployment rate was four times higher than that of whites. The only two local factories, both defense contractors, had agreed not to hire any Black workers, provided that the whites agreed not to unionize. All venues of entertainment, churches, cafes, and schools were segregated. Black schools received half as much funding as white schools. [1] Even though a third of Cambridge's residents were Black, there were only three Black police officers. These officers were not permitted to patrol white neighborhoods or arrest white individuals. [4]

On Christmas Eve of 1961, Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee Field Secretaries, Reggie Robinson and Bill Hansen, arrived and began organizing student protests. The Cambridge Movement, much like Freedom Summer, placed significant emphasis on voter education drives, but there were some differences. In Cambridge, local white residents did not react as violently to increased Black voter registration as they did in Mississippi. In fact, some white moderates even advocated for voter registration, viewing it as a better alternative to direct action protests in the streets and public facilities. Moreover, Black voter registration did not threaten the white majority as it did in the Black Belt in the American South. [4]

In 1962, the Cambridge Nonviolent Action Committee (CNAC) was organized to run these protests. Gloria Richardson and Inez Grubb both became the co-chairs of CNAC, which was the only SNCC affiliate not led by students. [5] The CNAC began picketing businesses that refused to hire Black people and conducted sit-ins at lunch-counters that would not serve Black individuals. White mobs often disrupted these protests. Protests on Race Street, which separated the Black and white communities, often turned violent. Cleveland Sellers, a SNCC Field Secretary, later reflected, "By the time we got to town, Cambridge's Black people had stopped extolling the virtues of passive resistance. Guns were carried as a matter of course and it was understood that they would be used." [3] Richardson defended such actions by the Black community, stating, "Self-defense may actually be a deterrent to further violence. Hitherto, the government has moved into conflict situations only when matters approach the level of insurrection."

In the spring of 1963, tensions rose steadily over a period of seven weeks. During this time, Richardson and 80 other protesters were arrested. By June, Black residents were rioting in the streets. [5] Maryland Governor J. Millard Tawes met with the protesters at a local school, offering to accelerate school desegregation, build public housing, and establish a biracial commission if the protests ceased. The CNAC rejected the deal. In response, Governor Tawes declared martial law and sent the National Guard to Cambridge. [6]

Potential violence near Washington, D.C., brought Cambridge to the attention of the Kennedy Administration. Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy initiated discussions with the CNAC. Together with the local city government, they arrived at an agreement aimed at averting possible violence. The agreement, named the 'Treaty of Cambridge,' proposed to desegregate public facilities, establish provisions for public housing, and create a human rights committee. However, it eventually fell through when the local government demanded that it should be passed by a local referendum. [3]

In May 1964, George Wallace, the segregationist Governor of Alabama, was invited by the DBCA, the city's primary business association, to give a campaign speech in Cambridge. Shortly after his arrival, black protesters appeared to protest his appearance, which incited a riot. [3]

Once the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was passed by Congress, the movement lost all momentum. The federal government had effectively mandated all that the CNAC had been fighting for. As the protests subsided, the National Guard withdrew. Subsequently, Gloria Richardson resigned from the CNAC and relocated to New York City. [5]

The civil rights movement was a nonviolent social movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized racial segregation, discrimination, and disenfranchisement in the country. The movement had its origins in the Reconstruction era during the late 19th century and had its modern roots in the 1940s, although the movement made its largest legislative gains in the 1960s after years of direct actions and grassroots protests. The social movement's major nonviolent resistance and civil disobedience campaigns eventually secured new protections in federal law for the civil rights of all Americans.

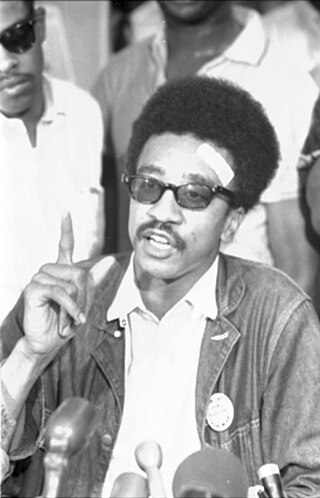

Jamil Abdullah al-Amin, is a human rights activist, Muslim cleric, black separatist, and convicted murderer who was the fifth chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) in the 1960s. Best known as H. Rap Brown, he served as the Black Panther Party's minister of justice during a short-lived alliance between SNCC and the Black Panther Party.

Bernice Johnson Reagon is a song leader, composer, scholar, and social activist, who in the early 1960s was a founding member of the Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee's (SNCC) Freedom Singers in the Albany Movement in Georgia. In 1973, she founded the all-black female a cappella ensemble Sweet Honey in the Rock, based in Washington, D.C. Reagon, along with other members of the SNCC Freedom Singers, realized the power of collective singing to unify the disparate groups who began to work together in the 1964 Freedom Summer protests in the South.

"After a song", Reagon recalled, "the differences between us were not so great. Somehow, making a song required an expression of that which was common to us all.... This music was like an instrument, like holding a tool in your hand."

The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee was the principal channel of student commitment in the United States to the civil rights movement during the 1960s. Emerging in 1960 from the student-led sit-ins at segregated lunch counters in Greensboro, North Carolina, and Nashville, Tennessee, the Committee sought to coordinate and assist direct-action challenges to the civic segregation and political exclusion of African Americans. From 1962, with the support of the Voter Education Project, SNCC committed to the registration and mobilization of black voters in the Deep South. Affiliates such as the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party and the Lowndes County Freedom Organization in Alabama also worked to increase the pressure on federal and state government to enforce constitutional protections.

Kwame Ture was a prominent organizer in the civil rights movement in the United States and the global pan-African movement. Born in Trinidad, he grew up in the United States from the age of 11 and became an activist while attending the Bronx High School of Science. He was a key leader in the development of the Black Power movement, first while leading the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), then as the "Honorary Prime Minister" of the Black Panther Party (BPP), and last as a leader of the All-African People's Revolutionary Party (A-APRP).

James Forman was a prominent African-American leader in the civil rights movement. He was active in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), the Black Panther Party, and the League of Revolutionary Black Workers. As the executive secretary of SNCC from 1961 to 1966, Forman played a significant role in the Freedom Rides, the Albany movement, the Birmingham campaign, and the Selma to Montgomery marches.

Gloria Richardson Dandridge was an American civil rights activist best known as the leader of the Cambridge movement, a civil rights action in the early 1960s in Cambridge, Maryland, on the Eastern Shore. Recognized as a major figure in the Civil Rights Movement, she was one of the signatories to "The Treaty of Cambridge", signed in July 1963 with Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, and state and local officials. It was an effort at reconciliation and commitment to change after a riot the month before.

Cleveland "Cleve" Sellers Jr. is an American educator and civil rights activist.

The Cambridge riots of 1963 were race riots that occurred during the summer of 1963 in Cambridge, a small city on the Eastern Shore of Maryland. The riots emerged during the Civil Rights Movement, locally led by Gloria Richardson and the local chapter of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. They were opposed by segregationists including the police.

The Freedom Singers originated as a quartet formed in 1962 at Albany State College in Albany, Georgia. After folk singer Pete Seeger witnessed the power of their congregational-style of singing, which fused black Baptist a cappella church singing with popular music at the time, as well as protest songs and chants. Churches were considered to be safe spaces, acting as a shelter from the racism of the outside world. As a result, churches paved the way for the creation of the freedom song. After witnessing the influence of freedom songs, Seeger suggested The Freedom Singers as a touring group to the SNCC executive secretary James Forman as a way to fuel future campaigns. Intrinsically connected, their performances drew aid and support to the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) during the emerging civil rights movement. As a result, communal song became essential to empowering and educating audiences about civil rights issues and a powerful social weapon of influence in the fight against Jim Crow segregation. Rutha Mae Harris, a former freedom singer, speculated that without the music force of broad communal singing, the civil rights movement may not have resonated beyond of the struggles of the Jim Crow South. Their most notable song “We Shall Not Be Moved” translated from the original Freedom Singers to the second generation of Freedom Singers, and finally to the Freedom Voices, made up of field secretaries from SNCC. "We Shall Not Be Moved" is considered by many to be the "face" of the Civil Rights movement. Rutha Mae Harris, a former freedom singer, speculated that without the music force of broad communal singing, the civil rights movement may not have resonated beyond of the struggles of the Jim Crow South. Since the Freedom Singers were so successful, a second group was created called the Freedom Voices.

Prathia Laura Ann Hall Wynn was an American leader and activist in the Civil Rights Movement, a womanist theologian, and ethicist. She was the key inspiration for Martin Luther King Jr.'s "I Have a Dream" speech.

The Cambridge riot of 1967 was one of 159 race riots that swept cities in the United States during the "Long Hot Summer of 1967". This riot occurred on July 24, 1967 in Cambridge, Maryland, a county seat on the Eastern Shore. For years racial tension had been high in Cambridge, where black people had been limited to second-class status. Activists had conducted protests since 1961, and there was a riot in June 1963 after the governor imposed martial law. "The Treaty of Cambridge" was negotiated among federal, state, and local leaders in July 1963, initiating integration in the city prior to passage of federal civil rights laws.

Judy Richardson is an American documentary filmmaker and civil rights activist. She was Distinguished Visiting Lecturer of Africana Studies at Brown University.

Charles E. "Charlie" Cobb Jr. is a journalist, professor, and former activist with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). Along with several veterans of SNCC, Cobb established and operated the African-American bookstore Drum and Spear in Washington, D.C., from 1968 to 1974. Currently he is a senior analyst at allAfrica.com and a visiting professor at Brown University.

The sit-in movement, sit-in campaign or student sit-in movement, were a wave of sit-ins that followed the Greensboro sit-ins on February 1, 1960 in North Carolina. The sit-in movement employed the tactic of nonviolent direct action and was a pivotal event during the Civil Rights Movement.

The Lowndes County Freedom Organization (LCFO), also known as the Lowndes County Freedom Party (LCFP) or Black Panther party, was an American political party founded during 1965 in Lowndes County, Alabama. The independent third party was formed by local African-American citizens led by John Hulett, and by staff members of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) under the leadership of Stokely Carmichael.

Stanley Everett Branche was an American civil rights leader from Pennsylvania who worked as executive secretary in the Chester, Pennsylvania branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and founded the Committee for Freedom Now (CFFN).

The Chester school protests were a series of demonstrations that occurred from November 1963 through April 1964 in Chester, Pennsylvania. The demonstrations aimed to end the de facto segregation of Chester public schools that persisted after the 1954 Supreme Court case Brown v. The Board of Education of Topeka. The racial unrest and civil rights protests were led by Stanley Branche of the Committee for Freedom Now (CFFN) and George Raymond of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored Persons (NAACP).

The Committee for Freedom Now (CFFN) was an American civil rights organization in Chester, Pennsylvania, that worked to end de facto segregation and improve the conditions at predominantly black schools in Chester. CFFN was founded in 1963 by Stanley Branche along with the Swarthmore College chapter of Students for a Democratic Society and Chester parents. From November 1963 to April 1964, CFFN and the Chester chapter of the NAACP, led by George Raymond, initiated the Chester school protests which made Chester a key battleground in the civil rights movement.

Martha Prescod Norman Noonan was a civil rights activist who is known for her work within the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and co-editing a 2012 book Hands on theFreedom Plow: Personal Accounts by Women in SNCC.