The American Civil War was a civil war in the United States between the Union and the Confederacy. The Confederacy had been formed by states that had seceded from the Union. The central conflict leading to the war was the dispute over whether slavery would be permitted to expand into the western territories, leading to more slave states, or be prevented from doing so, which many believed would place slavery on a course of ultimate extinction.

The Confederate States of America (CSA), commonly referred to as the Confederate States (C.S.), the Confederacy, or the South, was an unrecognized breakaway republic in the Southern United States that existed from February 8, 1861, to May 9, 1865. The Confederacy comprised eleven U.S. states that declared secession and warred against the United States during the American Civil War. The states were South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Texas, Virginia, Arkansas, Tennessee, and North Carolina.

The Canadian–American Reciprocity Treaty of 1854, also known as the Elgin-Marcy Treaty, was a treaty between the United Kingdom and the United States that applied to British North America, including the Province of Canada, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and Newfoundland Colony. The treaty covered raw materials; in effect from 1854 to 1866, it represented a move toward free trade and was opposed by protectionist elements in the United States.

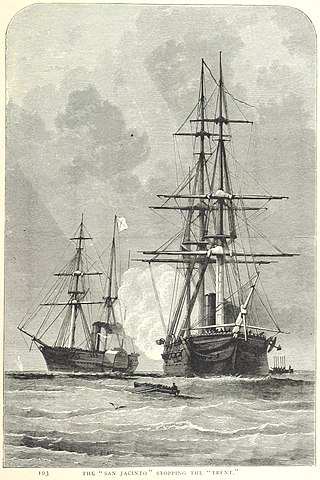

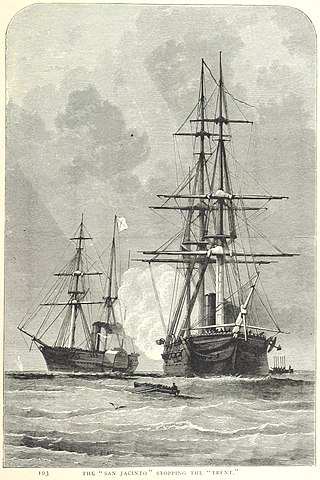

The Trent Affair was a diplomatic incident in 1861 during the American Civil War that threatened a war between the United States and Great Britain. The U.S. Navy captured two Confederate envoys from a British Royal Mail steamer; the British government protested vigorously. American public and elite opinion strongly supported the seizure, but it worsened the economy and was ruining relations with the world's strongest economy and strongest navy. President Abraham Lincoln ended the crisis by releasing the envoys.

Events from the year 1864 in Canada.

The Chesapeake Affair was an international diplomatic incident that occurred during the American Civil War. On December 7, 1863, Confederate sympathizers from the Maritime Provinces captured the American steamer Chesapeake off the coast of Cape Cod. The expedition was planned and led by Vernon Guyon Locke (1827–1890) of Nova Scotia and John Clibbon Brain (1840–1906). When George Wade of New Brunswick killed one of the American crew, the Confederacy claimed its first fatality in New England waters.

The Fenian raids were a series of incursions carried out by the Fenian Brotherhood, an Irish republican organization based in the United States, on military fortifications, customs posts and other targets in Canada in 1866, and again from 1870 to 1871. A number of separate incursions by the Fenian Brotherhood into Canada were undertaken to bring pressure on the British government to withdraw from Ireland, although none of these raids achieved their aims.

Cotton diplomacy was the attempt by the Confederacy during the American Civil War to coerce Great Britain and France to support the Confederate war effort by implementing a cotton trade embargo against Britain and the rest of Europe. The Confederacy believed that both Britain and France, who before the war depended heavily on Southern cotton for textile manufacturing, would support the Confederate war effort if the cotton trade were restricted. Ultimately, cotton diplomacy did not work in favor of the Confederacy; as European nations largely sought alternative markets to obtain cotton. In fact, the cotton embargo transformed into a self-embargo which restricted the Confederate economy. Ultimately, the growth in the demand for cotton that fueled the antebellum economy did not continue.

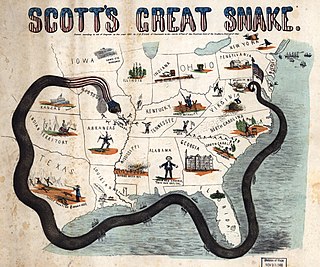

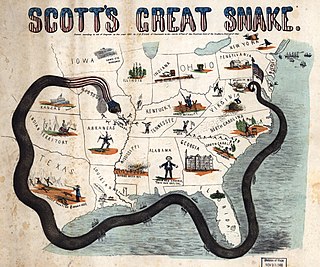

The Union blockade in the American Civil War was a naval strategy by the United States to prevent the Confederacy from trading.

"King Cotton" is a slogan that summarized the strategy used before the American Civil War by secessionists in the southern states to claim the feasibility of secession and to prove there was no need to fear a war with the northern states. The theory held that control over cotton exports would make a proposed independent Confederacy economically prosperous, would ruin the textile industry of New England, and—most importantly—would force the United Kingdom and perhaps France to support the Confederacy militarily because their industrial economies depended on Southern cotton.

The Confederate Secret Service refers to any of a number of official and semi-official secret service organizations and operations performed by the Confederate States of America during the American Civil War. Some of the organizations were directed by the Confederate government, others operated independently with government approval, while still others were either completely independent of the government or operated with only its tacit acknowledgment.

The history of Nova Scotia covers a period from thousands of years ago to the present day. Prior to European colonization, the lands encompassing present-day Nova Scotia were inhabited by the Mi'kmaq people. During the first 150 years of European settlement, the region was claimed by France and a colony formed, primarily made up of Catholic Acadians and Mi'kmaq. This time period involved six wars in which the Mi'kmaq along with the French and some Acadians resisted the British invasion of the region: the French and Indian Wars, Father Rale's War and Father Le Loutre's War. During Father Le Loutre's War, the capital was moved from Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia, to the newly established Halifax, Nova Scotia (1749). The warfare ended with the Burying the Hatchet ceremony (1761). After the colonial wars, New England Planters and Foreign Protestants immigrated to Nova Scotia. After the American Revolution, Loyalists immigrated to the colony. During the nineteenth century, Nova Scotia became self-governing in 1848 and joined the Canadian Confederation in 1867.

The Confederate privateers were privately owned ships that were authorized by the government of the Confederate States of America to attack the shipping of the United States. Although the appeal was to profit by capturing merchant vessels and seizing their cargoes, the government was most interested in diverting the efforts of the Union Navy away from the blockade of Southern ports, and perhaps to encourage European intervention in the conflict.

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland remained officially neutral throughout the American Civil War (1861–1865). It legally recognized the belligerent status of the Confederate States of America (CSA) but never recognized it as a nation and neither signed a treaty with it nor ever exchanged ambassadors. Over 90 percent of Confederate trade with Britain ended, causing a severe shortage of cotton by 1862. Private British blockade runners sent munitions and luxuries to Confederate ports in return for cotton and tobacco. In Manchester, the massive reduction of available American cotton caused an economic disaster referred to as the Lancashire Cotton Famine. Despite the high unemployment, some Manchester cotton workers refused out of principle to process any cotton from America, leading to direct praise from President Lincoln, whose statue in Manchester bears a plaque which quotes his appreciation for the textile workers in "helping abolish slavery". Top British officials debated offering to mediate in the first 18 months, which the Confederacy wanted but the United States strongly rejected.

The Second French Empire remained officially neutral throughout the American Civil War and never recognized the Confederate States of America. The United States warned that recognition would mean war. France was reluctant to act without British collaboration, and the British government rejected intervention.

Nova Scotia is a Canadian province located in Canada's Maritimes. The region was initially occupied by Mi'kmaq. The colonial history of Nova Scotia includes the present-day Maritime Provinces and the northern part of Maine, all of which were at one time part of Nova Scotia. In 1763, Cape Breton Island and St. John's Island became part of Nova Scotia. In 1769, St. John's Island became a separate colony. Nova Scotia included present-day New Brunswick until that province was established in 1784. During the first 150 years of European settlement, the colony was primarily made up of Catholic Acadians, Maliseet, and Mi'kmaq. During the last 75 years of this time period, there were six colonial wars that took place in Nova Scotia. After agreeing to several peace treaties, the long period of warfare ended with the Halifax Treaties (1761) and two years later, when the British defeated the French in North America (1763). During those wars, the Acadians, Mi'kmaq and Maliseet from the region fought to protect the border of Acadia from New England. They fought the war on two fronts: the southern border of Acadia, which New France defined as the Kennebec River in southern Maine, and in Nova Scotia, which involved preventing New Englanders from taking the capital of Acadia, Port Royal and establishing themselves at Canso.

During the American Civil War, blockade runners were used to get supplies through the Union blockade of the Confederate States of America that extended some 3,500 miles (5,600 km) along the Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico coastlines and the lower Mississippi River. The Confederacy had little industrial capability and could not indigenously produce the quantity of arms and other supplies needed to fight against the Union. To meet this need, numerous blockade runners were constructed in the British Isles and were used to import the guns, ordnance and other supplies that the Confederacy desperately needed, in exchange for cotton that the British textile industry needed greatly. To penetrate the blockade, these relatively lightweight shallow draft ships, mostly built in British shipyards and specially designed for speed, but not suited for transporting large quantities of cotton, had to cruise undetected, usually at night, through the Union blockade. The typical blockade runners were privately owned vessels often operating with a letter of marque issued by the Confederate government. If spotted, the blockade runners would attempt to outmaneuver or simply outrun any Union Navy warships on blockade patrol, often successfully.

The diplomacy of the American Civil War involved the relations of the United States and the Confederate States of America with the major world powers during the American Civil War of 1861–1865. The United States prevented other powers from recognizing the Confederacy, which counted heavily on Britain and France to enter the war on its side to maintain their supply of cotton and to weaken a growing opponent. Every nation was officially neutral throughout the war, and none formally recognized the Confederacy.

The economic history of the American Civil War concerns the financing of the Union and Confederate war efforts from 1861 to 1865, and the economic impact of the war.

Section 145 of the Constitution Act, 1867 is a repealed provision of the Constitution of Canada which required the federal government to build a railway connecting the River St. Lawrence with Halifax, Nova Scotia.