The Calusa were a Native American people of Florida's southwest coast. Calusa society developed from that of archaic peoples of the Everglades region. Previous indigenous cultures had lived in the area for thousands of years.

Pedro Menéndez de Avilés was a Spanish admiral, explorer and conquistador from Avilés, in Asturias, Spain. He is notable for planning the first regular trans-oceanic convoys, which became known as the Spanish treasure fleet, and for founding St. Augustine, Florida, in 1565. This was the first successful European settlement in La Florida and the most significant city in the region for nearly three centuries. St. Augustine is the oldest continuously inhabited, European-established settlement in the continental United States. Menéndez de Avilés was the first governor of La Florida (1565–74). By his contract, or asiento, with Philip II, Menéndez was appointed adelantado and was responsible for implementing royal policies to build fortifications for the defense of conquered territories in La Florida and to establish Castilian governmental institutions in desirable areas.

Tocobaga was the name of a chiefdom, its chief, and its principal town during the 16th century. The chiefdom was centered around the northern end of Old Tampa Bay, the arm of Tampa Bay that extends between the present-day city of Tampa and northern Pinellas County. The exact location of the principal town is believed to be the archeological Safety Harbor Site, which gives its name to the Safety Harbor culture, of which the Tocobaga are the most well-known group.

Hernando de Escalante Fontaneda was a Spanish shipwreck survivor who lived among the Native Americans of Florida for 17 years. His c. 1575 memoir, Memoria de las cosas y costa y indios de la Florida, is one of the most valuable contemporary accounts of American Indian life from that period. The manuscript can be found in the General Archive of the Indies. In all, he produced five documents describing the peoples of native Florida.

The Mayaimi were Native American people who lived around Lake Mayaimi in the Belle Glade area of Florida from the beginning of the Common Era until the 17th or 18th century. In the languages of the Mayaimi, Calusa, and Tequesta tribes, Mayaimi meant "big water." The origin of the language has not been determined, as the meanings of only ten words were recorded before extinction. The linguist Julian Granberry states that the language of the Calusa, Mayaimi and Tequesta people is related to the Tunica language. The current name, Okeechobee, is derived from the Hitchiti word meaning "big water". The Mayaimis have no linguistic or cultural relationship with the Miamis of Great Lakes region. The city of Miami is named after the Miami River, which derived its name from Lake Mayaimi.

The Diocese of Venice in Florida is a Latin Church ecclesiastical territory or diocese of the Catholic Church in Florida. It was founded on June 16, 1984 with the purpose of serving the southwestern portion of the state. The Diocese of Venice includes ten counties: Charlotte, Collier, DeSoto, Glades, Hardee, Hendry, Highlands, Lee, Manatee, and Sarasota.

Mound Key Archaeological State Park is a Florida State Park, located in Estero Bay, near the mouth of the Estero River. One hundred and thirteen of the island's one hundred and twenty-five acres are managed by the park system. It is a complex of mounds and accumulated shell, fish bone, and pottery middens that rises more than 30 feet above the waters of the bay.

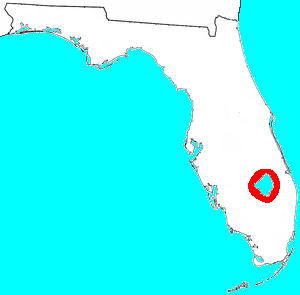

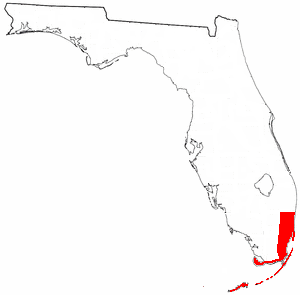

The Tequesta were a Native American tribe. At the time of first European contact they occupied an area along the southeastern Atlantic coast of Florida. They had infrequent contact with Europeans and had largely migrated by the middle of the 18th century.

The Ajacán Mission was a Spanish attempt in 1570 to establish a Jesuit mission in the vicinity of the Virginia Peninsula to bring Christianity to the Virginia Indians. The effort to found St. Mary's Mission predated the founding of the English settlement at Jamestown, Virginia, by about 36 years. In February 1571, the entire party was massacred by Indians except for Alonso de Olmos. The following year, a Spanish party from Florida went to the area, rescued Alonso, and killed an estimated 20 Indians.

Charlotte Harbor Estuary, the second largest bay in Florida, is located on the Gulf of Mexico coast of west Florida, mostly (2/3) in Charlotte County, Florida with the remaining 1/3 in Lee County. The harbor's mouth is located behind Gasparilla Island, one of the many coastal barrier islands on the southwest coast of Florida, with access from the Gulf of Mexico through the Boca Grande Pass between Gasparilla Island on the north and Lacosta Island on the south. Charlotte Harbor covers about 270 sq mi (700 km2)

The indigenous people of the Everglades region arrived in the Florida peninsula of what is now the United States approximately 14,000 to 15,000 years ago, probably following large game. The Paleo-Indians found an arid landscape that supported plants and animals adapted to prairie and xeric scrub conditions. Large animals became extinct in Florida around 11,000 years ago. Climate changes 6,500 years ago brought a wetter landscape. The Paleo-Indians slowly adapted to the new conditions. Archaeologists call the cultures that resulted from the adaptations Archaic peoples. They were better suited for environmental changes than their ancestors, and created many tools with the resources they had. Approximately 5,000 years ago, the climate shifted again to cause the regular flooding from Lake Okeechobee that gave rise to the Everglades ecosystems.

Mocoso was the name of a 16th-century chiefdom located on the east side of Tampa Bay, Florida near the mouth of the Alafia River, of its chief town and of its chief. Mocoso was also the name of a 17th-century village in the province of Acuera, a branch of the Timucua. The people of both villages are believed to have been speakers of the Timucua language.

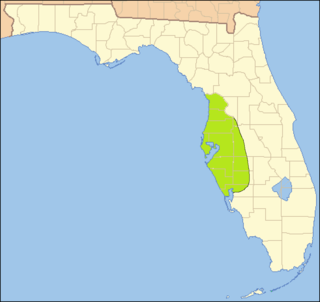

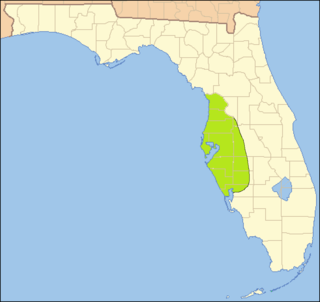

The Safety Harbor culture was an archaeological culture practiced by Native Americans living on the central Gulf coast of the Florida peninsula, from about 900 CE until after 1700. The Safety Harbor culture is defined by the presence of Safety Harbor ceramics in burial mounds. The culture is named after the Safety Harbor Site, which is close to the center of the culture area. The Safety Harbor Site is the probable location of the chief town of the Tocobaga, the best known of the groups practicing the Safety Harbor culture.

Muspa was the name of a town and a group of indigenous people in southwestern Florida in the early historic period, from first contact with the Spanish until indigenous peoples were gone from Florida, late in the 18th century.

Pohoy was a chiefdom on the shores of Tampa Bay in present-day Florida in the late sixteenth century and all of the seventeenth century. Following slave-taking raids by Hichiti language-speaking Muscogee people at the beginning of the eighteenth century, the surviving Pohoy people lived in several locations in peninsular Florida. The Pohoy disappeared from historical accounts after 1739.

Tomás Menéndez Márquez y Pedroso (1643–1706) was an official in the government of Spanish Florida, and owner, with his brothers, of the largest ranch in Spanish Florida. He was captured by pirates in 1682 and held for ransom, but was rescued by the Timucua.

Francisco Menéndez Márquez y Posada was a royal treasurer and interim co-governor of Spanish Florida, and the founder of a cattle ranching enterprise that became the largest in Florida.

Juan Fernández de Olivera was the governor of Spanish Florida from 1610 to November 23, 1612. He died in office.

Esteban de las Alas was a Spanish naval officer who served as interim governor of La Florida from October 1567 to August 1570, in the absence of official governor Pedro Menéndez de Avilés. He was also governor of the Spanish settlement of Santa Elena in what is now South Carolina, in 1566 and 1567.

San Antonio de Carlos, established in 1567, was the first Jesuit mission in the New World. The site is located in what is now Mound Key Archaeological State Park off Estero Bay in Florida and what was the cultural center of the Calusa or Calos people, who lived in the area for more than 2,000 years.