USS Napa was a Casco class twin-screw light draft monitor built during the American Civil War for operation in the shallow inland waters of the Confederacy. These warships sacrificed armor plate for a shallow draft and were fitted with a ballast compartment designed to lower them in the water during battle.

USS Yuma, a single-turreted, twin-screw monitor, was laid down at Cincinnati, OH, by Alexander Swift and Co. and launched on 30 May 1865. A Casco-class, light-draft monitor, she was intended for service in the shallow bays, rivers, and inlets of the Confederacy. These warships sacrificed armor plate for a shallow draft and were fitted with a ballast compartment designed to lower them in the water during battle.

USS Etlah, a single-turreted, twin-screw monitor, was still under construction at St. Louis, Missouri, at the close of the American Civil War. A Casco-class, light-draft monitor, she was intended for service in the shallow bays, rivers, and inlets of the Confederacy. These warships sacrificed armor plate for a shallow draft and were fitted with a ballast compartment designed to lower them in the water during battle.

The first USS Casco was the first of a class of twenty 1,175-ton light-draft monitors built by Atlantic Works, Boston, Massachusetts for the Union Navy during the American Civil War.

The first USS Naubuc, laid down as a 1,175-ton light-draft monitor at Perine's Union Iron Works, Williamsburgh, NY, was launched 19 October 1864. However, as with others of her class, she was of faulty design and was found to be unseaworthy prior to her completion. She was then converted to a torpedo boat, 4th rate, with one XI-inch Dahlgren smoothbore, and arid Wood-Lay spar torpedo equipment.

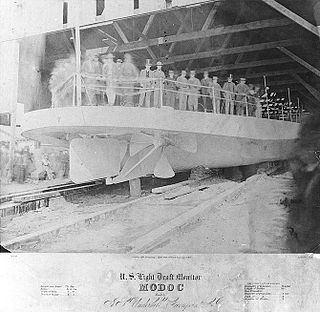

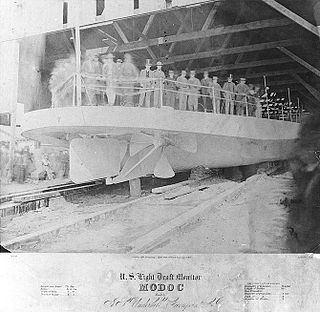

USS Modoc, a single turret, an 1,175-ton Casco-class light draft monitor built under contract by J. S. Underhill at Greenpoint, Brooklyn, was completed as a spar torpedo vessel in June 1865. She had no active service, spending her entire Navy career laid up "in ordinary" at Philadelphia. The vessel was renamed Achilles on 15 June 1869, but returned to Modoc on 10 August. The ship was broken up at New York in August 1875.

The first USS Tunxis was launched on 4 June 1864 at Chester, Pennsylvania, by Reaney, Son & Archbold; and commissioned at the Philadelphia Navy Yard on 12 July 1864. On 21 September 1864, the light-draft monitor departed the sheltered waters of the navy yard on her maiden voyage. However, she soon began taking on water at such an alarming rate that she came about and returned to Philadelphia where she was decommissioned later in the month.

USS Umpqua, a single-turreted, twin-screw monitor, was laid down in March 1863, before the official order had been placed, at Brownsville, Pennsylvania, by Snowden & Mason; launched on 21 December 1865; and completed on 7 May 1866.

USS Waxsaw, a single-turreted, twin-screw monitor, was laid down in March 1863, before the official order had been placed, at Baltimore, Maryland, by A. & W. Denmead & Son; launched on 4 May 1865; and completed on 21 October 1865.

USS Suncook – a single-turreted, twin-screw monitor – was built by the Globe Works, South Boston, and delivered to the government at the Boston Navy Yard on 8 July 1865.

USS Shiloh was a single-turreted, twin-screw monitor that was slated to enter service with the United States Navy. The contract for her construction was awarded on 24 June 1863 to George C. Bestor of Peoria, Illinois. Her keel was laid down later that year at the yard of Charles W. McCordat of St. Louis, Missouri. However, while Shiloh was still under construction, USS Chimo, one of the first of the Casco-class monitors to be launched, was found to be unseaworthy.

USS Cohoes — a single-turreted, twin-screw monitor — was still under construction at the close of the American Civil War. She was a Casco-class, light-draft monitor intended for service in the shallow bays, rivers, and inlets of the Confederacy. These warships sacrificed armor plate for a shallow draft and were fitted with a ballast compartment designed to lower them in the water during battle.

USS Klamath — a single-turreted, twin-screw monitor of the United States Navy — was launched 20 April 1865 by S. T. Hambleton & Co., Cincinnati, OH, under subcontract with Alexander Swift & Co., also of Cincinnati, OH. She was delivered to the Navy on 6 May 1866 but was never commissioned and saw no service.

USS Koka—a single-turreted, twin-screw monitor—was launched 18 May 1865 by Wilcox & Whiting, Camden, New Jersey. She was a Casco-class, light-draft monitor intended for service in the shallow bays, rivers, and inlets of the Confederacy. These warships sacrificed armor plate for a shallow draft and were fitted with a ballast compartment designed to lower them in the water during battle.

USS Nausett, a single-turreted, twin-screw monitor, was built by Donald McKay, South Boston, MA, and launched on 26 April 1865, and commissioned on 10 August 1865, Acting Master Win. U. Grozier in command. Soon after her commissioning, she steamed to New York, NY, where she decommissioned on 24 August 1865, and was laid up at the New York Navy Yard.

USS Wassuc — a single-turreted, twin-screw monitor — was built by the George W. Lawrence & Co., Portland, ME, and launched 25 July 1865, and completed 28 October 1865.

USS Shawnee was a single-turreted, twin-screw monitor built by Curtis & Tilden, Boston, Massachusetts, United States. It was delivered 22 July 1865, and commissioned 18 August 1865.

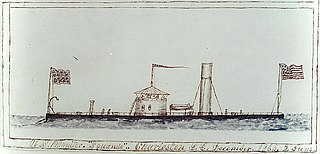

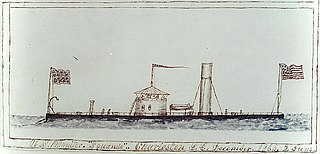

USS Chimo, a single-turreted, twin-screw monitor, was built by the Aquila Adams company in South Boston, Massachusetts, and launched 5 May 1864, and commissioned 20 January 1865.

USS Squando was a Casco-class light draft monitor built during the American Civil War. Designed for service in rivers, the class required design changes due to the lack of seaworthiness of the first Casco-class vessel. Squando required her deck to be raised 22 inches (56 cm) before completion in order to provide more freeboard. Launched in late December 1864 or early January 1865, she was commissioned on June 6, 1865. Completed after the American Civil War had wound down, she served in the North Atlantic Squadron in 1865 and 1866 before being decommissioned in May of the latter year. After being renamed twice in 1869, she was sold in 1874 and then broken up.

Alban Crocker Stimers was a Chief Engineer with the United States Navy. He assisted with the design of the Navy's first ironclad, the USS Monitor, and later with the design of the Passaic-class monitors. His later career was marred by the scandal which enveloped the Casco-class monitors after they were found to be unseaworthy.