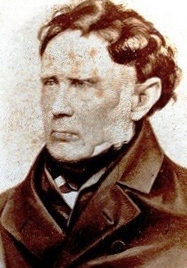

Charles Pacalt Brownlee CMG (1821- 13 September 1890) was a politician and writer of the Cape Colony. He was the first Secretary for Native Affairs in the Cape. [1]

Charles Pacalt Brownlee CMG (1821- 13 September 1890) was a politician and writer of the Cape Colony. He was the first Secretary for Native Affairs in the Cape. [1]

Born in 1821, the son of the linguist, botanist and missionary, John Brownlee, who founded King William's Town in 1825. From his childhood, living among the Xhosa people of the Cape's eastern frontier, Charles Brownlee and his brother James grew up with mother-tongue fluency in the Xhosa language and culture. As teenagers, the brothers were employed by missionaries travelling to the Zulu Kingdom. Although Charles soon returned to the Cape, his brother was in Zululand during the Piet Retief Delegation massacre and was tasked with untangling the bodies from the still-living horses. [2]

He was initially recorded as working as a guide to Governor Sir Harry Smith in 1846, during the frontier war. His detailed and invaluable local knowledge as well as his bravery were remarked upon, and he was soon appointed "Gaika Commissioner" in 1849 ("Gaika" was the English name at the time for the " Ngqika " branch of the Xhosa nation). He was made "Diplomatic Commissioner amongst the Gaikas" in 1851. [3]

During the ongoing frontier wars that afflicted the vanguard of British expansion in southern Africa, Brownlee played a difficult and sometimes very awkward role as a peacemaker and cultural intermediary - sympathetic to Xhosa grievances but unable to restrain British expansion. (His unfortunate brother James Brownlee was involved in the conflict too and, in an ambush on 28 March 1851, was killed and subsequently beheaded.) [4]

Charles Brownlee's position was done away with in 1868, when colonial policy changed, and Brownlee was re-appointed as "Civil Commissioner" for several districts of the Cape frontier, including King William's Town. [5]

In 1872, the Cape attained Responsible Government under the leadership of its first Prime Minister, John Molteno, and direct British rule ended.

Less interested in annexing or settling Xhosa land than the Colonial Office, the new Cape government was more concerned with ways to secure and stabilise the frontier, so that it could concentrate on internal development. In their opinion, a stable border required trust and good relations with the tribes of the neighbouring Transkei region. It also required that good relations were established with the minority of Xhosa who lived within the Cape's frontiers under traditional tribal authority - rather than under the Cape's direct laws. (The Cape had a non-racial constitution, with the multi-racial Cape Qualified Franchise system for all voters regardless of race, but many rural Xhosa remained legally subject to tribal law.)

A system of communication and understanding with these tribal authorities, who controlled much of the land on - and beyond - the Cape's eastern frontier, was thus a primary concern of the new government. So much so, that the new Prime Minister saw fit to create an entire ministry for this purpose. He also explicitly wanted a minister in his cabinet who was openly sympathetic to the Xhosa, understood their main issues and spoke their language. For this reason, he chose Charles Brownlee for this important position, later named Secretary for Native Affairs, and Brownlee gratefully resigned his Commissionership to move into government. [6]

For several years, Brownlee presided over the beginnings of a peace. The new government held back white expansion into Xhosa lands, while offering equal political rights to Black Africans who were citizens of the Cape. Liberals, such as the great Saul Solomon, held sway in the Cape Town parliament, and the frontier quietened and stabilised.

The lynch-pin to Brownlee's "native policy" and the primary reason for its relative success, was the legal recognition given to traditional Xhosa systems of land tenure, and the cutting of discriminatory taxation on this land. This gave protection from dispossession and abuse by white settlers, and removed one of the key grievances of the Xhosa. The policy of the government at the time was to recognise and respect the authority of the traditional Chiefs over their rural subjects, but that when Xhosa people urbanised or moved out of the tribal areas they became subject to the Cape's overall laws. Although this was intended as a compromise between forceful assimilation on the one hand and segregation on the other, it was also seen as gradually undermining the authority of traditional chiefs.

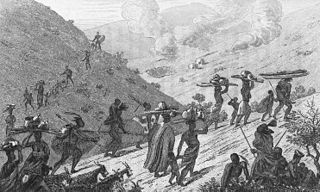

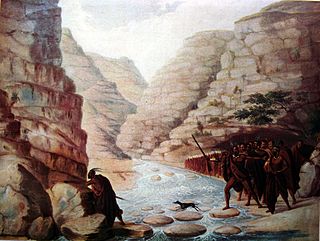

Beginning in the mid-1870s however, the Colonial Office became interested in more direct control of the Cape, mainly for the purpose of pushing an ill-advised plan to annex the remaining independent states in Southern Africa and to impose a system of confederation on them (similar to the Canadian Confederation. This involvement sparked conflicts across the region, culminating in the 9th Xhosa War and the First Boer War. Brownlee and the Cape government strongly opposed both the disastrous confederation scheme and the Colonial Office's expansionist policies, leading to a political collision between the Cape Government and the British imperial government based in London.

Imperial interference in a minor tribal confrontation between the Mfengu and Gcaleka tribes on the frontier led to the tribal confrontation to contribute to the outbreak of the Ninth Xhosa War. As the Cape government struggled to prevent further imperial interference, Brownlee was sent to the Cape frontier to negotiate a settlement with the Xhosa.

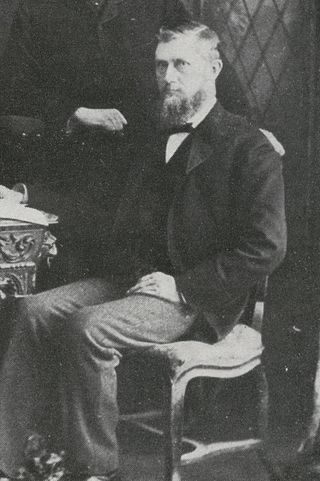

The governor of the Cape, Welshman Sir Henry Bartle Frere, who had taken over control of the frontier war and was bringing in imperial troops, ordered Brownlee instead to disarm all of the Cape's Black African subjects, soldiers and auxiliaries. Brownlee strongly disagreed with this policy, as did the Cape government, but was forced to carry it out, to the fury of many in the Cape. Brownlee rapidly found himself caught between three opposing forces: the Cape government, Bartle Frere, and the Xhosa. Under immense pressure, he came under criticism from all parties for his indecisive actions and consequent mishandling of the disarmament. John Molteno expected him to stand up to Frere, Bartle Frere expected him to obey his orders without question or hesistation, and the Xhosa lost all faith in him as a reliable intermediary.

Brownlee lost his job in 1878, when the Colonial Office suspended the Cape's elected parliament, and assumed direct imperial control over the Cape Colony. As the resulting "confederation wars" swept the sub-continent, [7] Brownlee fell back on the position of Chief Magistrate of Griqualand East, and held this position until his retirement in 1885.

He died on 13 September 1890. [8]

The year 1870 in the history of the Cape Colony marks the dawn of a new era in South Africa, and it can be said that the development of modern South Africa began on that date. Despite political complications that arose from time to time, progress in Cape Colony continued at a steady pace until the outbreak of the Anglo-Boer Wars in 1899. The discovery of diamonds in the Orange River in 1867 was immediately followed by similar finds in the Vaal River. This led to the rapid occupation and development of huge tracts of the country, which had hitherto been sparsely inhabited. Dutoitspan and Bultfontein diamond mines were discovered in 1870, and in 1871 the even richer mines of Kimberley and De Beers were discovered. These four great deposits of mineral wealth were incredibly productive, and constituted the greatest industrial asset that the Colony possessed.

The history of the Cape Colony from 1806 to 1870 spans the period of the history of the Cape Colony during the Cape Frontier Wars, which lasted from 1779 to 1879. The wars were fought between the European colonists and the native Xhosa who, defending their land, fought against European rule.

Sir Henry Bartle Edward Frere, 1st Baronet, was a British colonial administrator. He had a successful career in India, rising to become Governor of Bombay (1862–1867). However, as High Commissioner for Southern Africa (1877–1880), he implemented a set of policies which attempted to impose a British confederation on the region and which led to the overthrow of the Cape's first elected government in 1878 and to a string of regional wars, culminating in the invasion of Zululand (1879) and the First Boer War (1880–1881). The British Prime Minister, Gladstone, recalled Frere to London to face charges of misconduct; Whitehall officially censured Frere for acting recklessly.

Sir Theophilus Shepstone was a British South African statesman who was responsible for the annexation of the Transvaal to Britain in 1877. Shepstone is the great great grandfather of international artist Conor Mccreedy.

The following lists events that happened during 1877 in South Africa.

The amaMfengu was a reference of Xhosa clans whose ancestors were refugees that fled from the Mfecane in the early-mid 19th century to seek land and protection from the Xhosa. These refugees were assimilated into the Xhosa nation and were officially recognized by the then king, Hintsa. The term derives from the Xhosa verb "ukumfenguza" which means to wander about seeking service.

British Kaffraria was a British colony/subordinate administrative entity in present-day South Africa, consisting of the districts now known as Qonce and East London. It was also called Queen Adelaide's Province and, unofficially, British Kaffiria and Kaffirland.

Sir Andries Stockenström, 1st Baronet, was lieutenant governor of British Kaffraria from 13 September 1836 to 9 August 1838.

The Cape Mounted Riflemen were South African military units.

The Xhosa Wars were a series of nine wars between the Xhosa Kingdom and the British Empire as well as Trekboers in what is now the Eastern Cape in South Africa. These events were the longest-running military action in the history of European colonialism in Africa.

King Sarhili was the King of Xhosa nation from 1835 until his death in 1892 at Sholora, Bomvanaland. He was also known as "Kreli", and led the Xhosa armies in a series of frontier wars.

Sir John Gordon Sprigg, was an English-born colonial administrator and politician who served as prime minister of the Cape Colony on four different occasions.

Sir John Charles Molteno was a soldier, businessman, champion of responsible government and the first Prime Minister of the Cape Colony.

Sir Thomas Charles Scanlen was a politician and administrator of the Cape Colony.

The South African Wars, including but also known as the Confederation Wars, were a series of wars that occurred in the southern portion of the African continent between 1879 and 1915. Ethnic, political, and social tensions between European colonial powers and indigenous Africans led to increasing hostilities, culminating in a series of wars and revolts, which had lasting repercussions on the entire region. A key factor behind the growth of these tensions was the pursuit of commerce and resources, both by countries and individuals, especially following the discoveries of diamonds in the region in 1867 and gold in 1862.

John ("Jock") Paterson was a prominent politician and successful businessman of the Cape Colony, and had a great influence on the development of Port Elizabeth where he was based. He ran newspapers, established the Grey Institute and played a significant role in founding South Africa's Standard Bank.

Sir Charles Abercrombie Smith was a Cape Colony scientist, politician and civil servant.

Robert Godlonton (1794–1884) was an influential politician of the Cape Colony. He was an 1820 Settler, who developed the press of the Eastern Cape and led the Eastern Cape separatist movement as a representative in the Cape's Legislative Council.

The Palgrave Commission (1876–1885) was a series of diplomatic missions undertaken by Special Commissioner William Coates Palgrave (1833–1897) to the territory of South West Africa. Palgrave was commissioned by the Cape Government to meet with the leaders of the nations of Hereroland and Namaland, hear their wishes regarding political sovereignty, and relay the assembled information to the Cape Colony Government.

The Eastern Province Separatist League was a loose political movement of the 19th century Cape Colony. It fought not for independence, but for a separate colony in the eastern half of the Cape Colony independent from the Cape government, with a more restrictive political system and an expansionist policy eastwards against the remaining independent Xhosa states. It was crushed in the 1870s, and many of its members later moved to the new pro-imperialist, Rhodesian “progressive party”.