There has been a significant history of Chinese immigration to Canada, with the first settlement of Chinese people in Canada being in the 1780s. The major periods of Chinese immigration would take place from 1858 to 1923 and 1947 to the present day, reflecting changes in the Canadian government's immigration policy.

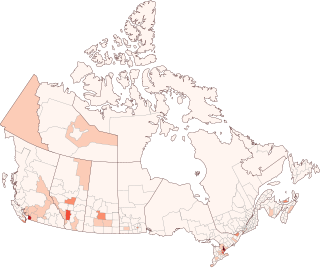

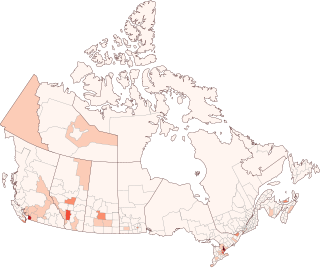

Chinese Canadians are Canadians of full or partial Han Chinese ancestry, which includes both naturalized Chinese immigrants and Canadian-born Chinese. They comprise a subgroup of East Asian Canadians which is a further subgroup of Asian Canadians. Demographic research tends to include immigrants from Mainland China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Macau, as well as overseas Chinese who have immigrated from Southeast Asia and South America into the broadly defined Chinese Canadian category.

Chinatown is a neighbourhood in Vancouver, British Columbia, and is Canada's largest Chinatown. Centred around Pender Street, it is surrounded by Gastown to the north, the Downtown financial and central business districts to the west, the Georgia Viaduct and the False Creek inlet to the south, the Downtown Eastside and the remnant of old Japantown to the northeast, and the residential neighbourhood of Strathcona to the southeast.

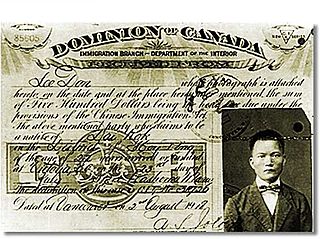

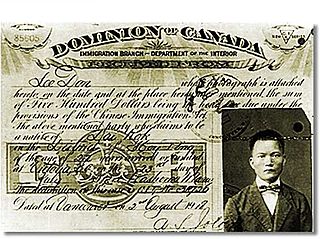

The Chinese head tax was a fixed fee charged to each Chinese person entering Canada. The head tax was first levied after the Canadian parliament passed the Chinese Immigration Act of 1885 and it was meant to discourage Chinese people from entering Canada after the completion of the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR). The tax was abolished by the Chinese Immigration Act of 1923, which outright prevented all Chinese immigration except for that of business people, clergy, educators, students, and some others.

The Asiatic Exclusion League was an organization formed in the early 20th century in the United States and Canada that aimed to prevent immigration of people of Asian origin.

The Komagata Maru incident involved the Japanese steamship Komagata Maru, on which a group of people from British India attempted to immigrate to Canada in April 1914, but most were denied entry and forced to return to Budge Budge, Calcutta. There, the Indian Imperial Police attempted to arrest the group leaders. A riot ensued, and they were fired upon by the police, resulting in some deaths.

The Chinese Immigration Act, 1885 was an Act of the Parliament of Canada that placed a head tax of $50 on all Chinese immigrants entering Canada. It was based on the recommendations of the Royal Commission on Chinese Immigration, which were published in 1885.

According to the 2021 Canadian census, immigrants in Canada number 8.3 million persons and make up approximately 23 percent of Canada's total population. This represents the eighth-largest immigrant population in the world, while the proportion represents one of the highest ratios for industrialized Western countries.

Canadian immigration and refugee law concerns the area of law related to the admission of foreign nationals into Canada, their rights and responsibilities once admitted, and the conditions of their removal. The primary law on these matters is in the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act, whose goals include economic growth, family reunification, and compliance with humanitarian treaties.

New Zealand imposed a poll tax on Chinese immigrants during the 19th and early 20th centuries. The poll tax was effectively lifted in the 1930s following the invasion of China by Japan, and was finally repealed in 1944. Following efforts to recognise its impact, an apology for the tax was issued in English and Mandarin under prime minister Helen Clark in 2002, and was later delivered in Cantonese in 2023.

Sikhism in Canada has nearly 800,000 adherents who account for 2.1% of Canada's population as of 2021, forming the country's fastest-growing and fourth-largest religious group. The largest Sikh populations in Canada are found in Ontario, followed by British Columbia and Alberta. As of the 2021 Census, more than half of Canada's Sikhs can be found in one of four cities: Brampton (163,260), Surrey (154,415), Calgary (49,465), and Edmonton (41,385).

Asian Canadians are Canadians who were either born in or can trace their ancestry to the continent of Asia. Canadians with Asian ancestry comprise both the largest and fastest growing group in Canada, after European Canadians, forming approximately 20.2 percent of the Canadian population as of 2021. Most Asian Canadians are concentrated in the urban areas of Southern Ontario, Southwestern British Columbia, Central Alberta, and other large Canadian cities.

The continuous journey regulation was a restriction placed by the Canadian government that (ostensibly) prevented those who, "in the opinion of the Minister of the Interior," did not "come from the country of their birth or citizenship by a continuous journey and or through tickets purchased before leaving the country of their birth or nationality" from being accepted as immigrants to Canada. However, in effect, the regulation would only affect the immigration of persons from India.

Racism in Canada traces both historical and contemporary racist community attitudes, as well as governmental negligence and political non-compliance with United Nations human rights standards and incidents in Canada. Contemporary Canada is the product of indigenous First Nations combined with multiple waves of immigration, predominantly from Europe and in modern times, from Asia.

The Vancouver riots occurred September 7–9, 1907, in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. At about the same time there were similar anti-Asian riots in Bellingham, Washington, San Francisco, and other West Coast cities. They were not coordinated but instead reflected common underlying anti-immigration attitudes. Agitation for direct action was led by labour unions and small business. No one was killed but the damage to Asian-owned property was extensive.

The history of Chinese Canadians in British Columbia began with the first recorded visit by Chinese people to North America in 1788. Some 30–40 men were employed as shipwrights at Nootka Sound in what is now British Columbia, to build the first European-type vessel in the Pacific Northwest, named the North West America. Large-scale immigration of Chinese began seventy years later with the advent of the Fraser Canyon Gold Rush of 1858. During the gold rush, settlements of Chinese grew in Victoria and New Westminster and the "capital of the Cariboo" Barkerville and numerous other towns, as well as throughout the colony's interior, where many communities were dominantly Chinese. In the 1880s, Chinese labour was contracted to build the Canadian Pacific Railway. Following this, many Chinese began to move eastward, establishing Chinatowns in several of the larger Canadian cities.

Paper sons or paper daughters is a term used to refer to Chinese people who were born in China and illegally immigrated to the United States and Canada by purchasing documentation which stated that they were blood relatives to Chinese people who had already received U.S. or Canadian citizenship or residency. Typically it would be relation by being a son or a daughter. Several historical events such as the Chinese Exclusion Act and San Francisco earthquake of 1906 caused the illegal documents to be produced.

The Royal Commission on Chinese Immigration was a commission of inquiry appointed to establish whether or not imposing restrictions to Chinese immigration to Canada was in the country's best interest. Ordered on 4 July 1884 by Prime Minister John A. Macdonald, the inquiry was appointed two commissioners were: the Honorable Joseph-Adolphe Chapleau, LL.D., who was the Secretary of State for Canada; and the Honorable John Hamilton Gray, DCL, a Justice on the Supreme Court of British Columbia.

East Asian Canadians are Canadians who were either born in or can trace their ancestry to East Asia. East Asian Canadians are also a subgroup of Asian Canadians. According to Statistics Canada, East Asian Canadians are considered visible minorities and can be further divided by on the basis of both ethnicity and nationality, such as Chinese Canadian, Hong Kong Canadian, Japanese Canadian, Korean Canadian, Mongolian Canadian, Taiwanese Canadian, or Tibetan Canadian, as seen on demi-decadal census data.

Until 1965, racial segregation in schools, stores and most aspects of public life existed legally in Ontario, Quebec and Nova Scotia, and informally in other provinces such as British Columbia. Unlike in the United States, racial segregation in Canada applied to all non-whites and was historically enforced through laws, court decisions and social norms with a closed immigration system that barred virtually all non-whites from immigrating until 1962. Section 38 of the 1910 Immigration Act permitted the government to prohibit the entry of immigrants "belonging to any race deemed unsuited to the climate or requirements of Canada, or of immigrants of any specified class, occupation or character."