Hypoglycemia, also called low blood sugar, is a fall in blood sugar to levels below normal, typically below 70 mg/dL (3.9 mmol/L). Whipple's triad is used to properly identify hypoglycemic episodes. It is defined as blood glucose below 70 mg/dL (3.9 mmol/L), symptoms associated with hypoglycemia, and resolution of symptoms when blood sugar returns to normal. Hypoglycemia may result in headache, tiredness, clumsiness, trouble talking, confusion, fast heart rate, sweating, shakiness, nervousness, hunger, loss of consciousness, seizures, or death. Symptoms typically come on quickly.

An insulin pump is a medical device used for the administration of insulin in the treatment of diabetes mellitus, also known as continuous subcutaneous insulin therapy. The device configuration may vary depending on design. A traditional pump includes:

The following is a glossary of diabetes which explains terms connected with diabetes.

Hyperglycemia is a condition in which an excessive amount of glucose circulates in the blood plasma. This is generally a blood sugar level higher than 11.1 mmol/L (200 mg/dL), but symptoms may not start to become noticeable until even higher values such as 13.9–16.7 mmol/L (~250–300 mg/dL). A subject with a consistent fasting blood glucose range between ~5.6 and ~7 mmol/L is considered slightly hyperglycemic, and above 7 mmol/L is generally held to have diabetes. For diabetics, glucose levels that are considered to be too hyperglycemic can vary from person to person, mainly due to the person's renal threshold of glucose and overall glucose tolerance. On average, however, chronic levels above 10–12 mmol/L (180–216 mg/dL) can produce noticeable organ damage over time.

Diabetic coma is a life-threatening but reversible form of coma found in people with diabetes mellitus.

The blood sugar level, blood sugar concentration, blood glucose level, or glycemia, is the measure of glucose concentrated in the blood. The body tightly regulates blood glucose levels as a part of metabolic homeostasis.

Diabetes is a chronic disease in cats whereby either insufficient insulin response or insulin resistance leads to persistently high blood glucose concentrations. Diabetes affects up to 1 in 230 cats, and may be becoming increasingly common. Diabetes is less common in cats than in dogs. The condition is treatable, and if treated properly the cat can experience a normal life expectancy. In cats with type 2 diabetes, prompt effective treatment may lead to diabetic remission, in which the cat no longer needs injected insulin. Untreated, the condition leads to increasingly weak legs in cats and eventually to malnutrition, ketoacidosis and/or dehydration, and death.

Hyperinsulinemia is a condition in which there are excess levels of insulin circulating in the blood relative to the level of glucose. While it is often mistaken for diabetes or hyperglycaemia, hyperinsulinemia can result from a variety of metabolic diseases and conditions, as well as non-nutritive sugars in the diet. While hyperinsulinemia is often seen in people with early stage type 2 diabetes mellitus, it is not the cause of the condition and is only one symptom of the disease. Type 1 diabetes only occurs when pancreatic beta-cell function is impaired. Hyperinsulinemia can be seen in a variety of conditions including diabetes mellitus type 2, in neonates and in drug-induced hyperinsulinemia. It can also occur in congenital hyperinsulinism, including nesidioblastosis.

Diabetic hypoglycemia is a low blood glucose level occurring in a person with diabetes mellitus. It is one of the most common types of hypoglycemia seen in emergency departments and hospitals. According to the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System-All Injury Program (NEISS-AIP), and based on a sample examined between 2004 and 2005, an estimated 55,819 cases involved insulin, and severe hypoglycemia is likely the single most common event.

Reactive hypoglycemia, postprandial hypoglycemia, or sugar crash is a term describing recurrent episodes of symptomatic hypoglycemia occurring within four hours after a high carbohydrate meal in people with and without diabetes. The term is not necessarily a diagnosis since it requires an evaluation to determine the cause of the hypoglycemia.

Type 1 diabetes (T1D), formerly known as juvenile diabetes, is an autoimmune disease that originates when cells that make insulin are destroyed by the immune system. Insulin is a hormone required for the cells to use blood sugar for energy and it helps regulate glucose levels in the bloodstream. Before treatment this results in high blood sugar levels in the body. The common symptoms of this elevated blood sugar are frequent urination, increased thirst, increased hunger, weight loss, and other serious complications. Additional symptoms may include blurry vision, tiredness, and slow wound healing. Symptoms typically develop over a short period of time, often a matter of weeks if not months.

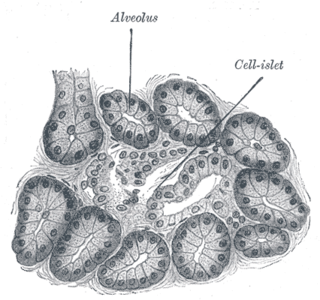

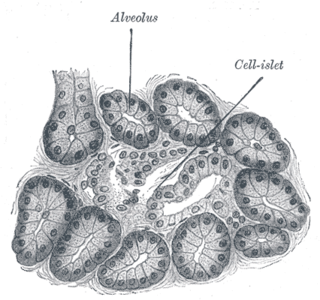

The term diabetes includes several different metabolic disorders that all, if left untreated, result in abnormally high concentrations of a sugar called glucose in the blood. Diabetes mellitus type 1 results when the pancreas no longer produces significant amounts of the hormone insulin, usually owing to the autoimmune destruction of the insulin-producing beta cells of the pancreas. Diabetes mellitus type 2, in contrast, is now thought to result from autoimmune attacks on the pancreas and/or insulin resistance. The pancreas of a person with type 2 diabetes may be producing normal or even abnormally large amounts of insulin. Other forms of diabetes mellitus, such as the various forms of maturity-onset diabetes of the young, may represent some combination of insufficient insulin production and insulin resistance. Some degree of insulin resistance may also be present in a person with type 1 diabetes.

For pregnant women with diabetes, some particular challenges exist for both mother and fetus. If the pregnant woman has diabetes as a pre-existing disorder, it can cause early labor, birth defects, and larger than average infants. Therefore, experts advise diabetics to maintain blood sugar level close to normal range about 3 months before planning for pregnancy.

Alpha-glucosidase inhibitors (AGIs) are oral anti-diabetic drugs used for diabetes mellitus type 2 that work by preventing the digestion of carbohydrates. Carbohydrates are normally converted into simple sugars (monosaccharides) by alpha-glucosidase enzymes present on cells lining the intestine, enabling monosaccharides to be absorbed through the intestine. Hence, alpha-glucosidase inhibitors reduce the impact of dietary carbohydrates on blood sugar.

A diabetic diet is a diet that is used by people with diabetes mellitus or high blood sugar to minimize symptoms and dangerous complications of long-term elevations in blood sugar.

Blood sugar regulation is the process by which the levels of blood sugar, the common name for glucose dissolved in blood plasma, are maintained by the body within a narrow range.

The dawn phenomenon, sometimes called the dawn effect, is an observed increase in blood sugar (glucose) levels that takes place in the early-morning, often between 2 a.m. and 8 a.m. First described by Schmidt in 1981 as an increase of blood glucose or insulin demand occurring at dawn, this naturally occurring phenomenon is frequently seen among the general population and is clinically relevant for patients with diabetes as it can affect their medical management. In contrast to Chronic Somogyi rebound, the dawn phenomenon is not associated with nocturnal hypoglycemia.

Complications of diabetes are secondary diseases that are a result of elevated blood glucose levels that occur in diabetic patients. These complications can be divided into two types: acute and chronic. Acute complications are complications that develop rapidly and can be exemplified as diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), hyperglycemic hyperosmolar state (HHS), lactic acidosis (LA), and hypoglycemia. Chronic complications develop over time and are generally classified in two categories: microvascular and macrovascular. Microvascular complications include neuropathy, nephropathy, and retinopathy; while cardiovascular disease, stroke, and peripheral vascular disease are included in the macrovascular complications.

Diabetes mellitus is a disease in which the beta cells of the endocrine pancreas either stop producing insulin or can no longer produce it in enough quantity for the body's needs. The disease can affect humans as well as animals such as dogs.

Mladen Vranic, MD, DSc, O.C., O.Ont, FRSC, FRCP(C), FCAHS, Canadian Medical Hall of Fame[CMHF] April 3, 1930 – June 18, 2019, was a Croatian-born diabetes researcher, best known for his work in tracer methodology, exercise and stress in diabetes, the metabolic effects of hormonal interactions, glucagon physiology, extrapancreatic glucagon, the role of the direct and indirect metabolic effects of insulin and the prevention of hypoglycemia. Vranic was recognized by a number of national and international awards for his research contributions, mentoring and administration including the Orders of Canada (Officer) and Ontario.