A book is a medium for recording information in the form of writing or images, typically composed of many pages bound together and protected by a cover. The technical term for this physical arrangement is codex. In the history of hand-held physical supports for extended written compositions or records, the codex replaces its predecessor, the scroll. A single sheet in a codex is a leaf and each side of a leaf is a page.

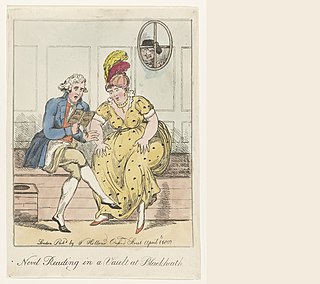

Crime fiction, detective story, murder mystery, mystery novel, and police novel are terms used to describe narratives that centre on criminal acts and especially on the investigation, either by an amateur or a professional detective, of a crime, often a murder. It is usually distinguished from mainstream fiction and other genres such as historical fiction or science fiction, but the boundaries are indistinct. Crime fiction has multiple subgenres, including detective fiction, courtroom drama, hard-boiled fiction, and legal thrillers. Most crime drama focuses on crime investigation and does not feature the courtroom. Suspense and mystery are key elements that are nearly ubiquitous to the genre.

Ann Radcliffe was an English novelist and a pioneer of Gothic fiction. Her technique of explaining apparently supernatural elements in her novels has been credited with gaining respectability for Gothic fiction in the 1790s. Radcliffe was the most popular writer of her day and almost universally admired; contemporary critics called her the mighty enchantress and the Shakespeare of romance-writers, and her popularity continued through the 19th century. Interest has revived in the early 21st century, with the publication of three biographies.

A public library is a library that is accessible by the general public and is usually funded from public sources, such as taxes. It is operated by librarians and library paraprofessionals, who are also civil servants.

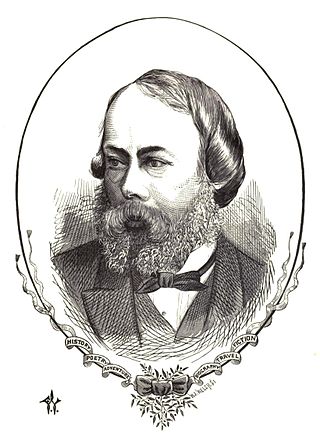

George Augustus Moore was an Irish novelist, short-story writer, poet, art critic, memoirist and dramatist. Moore came from a Roman Catholic landed family who lived at Moore Hall in Carra, County Mayo. He originally wanted to be a painter, and studied art in Paris during the 1870s. There, he befriended many of the leading French artists and writers of the day.

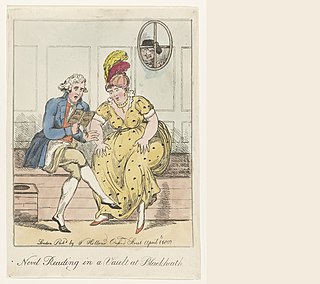

A romance novel or romantic novel generally refers to a type of genre fiction novel which places its primary focus on the relationship and romantic love between two people, and usually has an "emotionally satisfying and optimistic ending." Precursors include authors of literary fiction, such as Samuel Richardson, Jane Austen, and Charlotte Brontë.

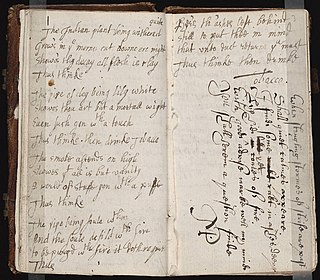

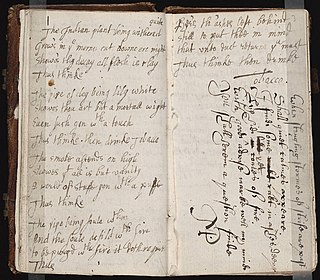

Commonplace books are a way to compile knowledge, usually by writing information into books. They have been kept from antiquity, and were kept particularly during the Renaissance and in the nineteenth century. Such books are similar to scrapbooks filled with items of many kinds: sententiae, notes, proverbs, adages, aphorisms, maxims, quotes, letters, poems, tables of weights and measures, prayers, legal formulas, and recipes. Entries are most often organized under subject headings and differ functionally from journals or diaries, which are chronological and introspective." Commonplaces are used by readers, writers, students, and scholars as an aid for remembering useful concepts or facts; sometimes they were required of young women as evidence of their mastery of social roles and as demonstrations of the correctness of their upbringing. They became significant in Early Modern Europe.

A chapbook is a small publication of up to about 40 pages, sometimes bound with a saddle stitch.

Mills & Boon is a romance imprint of British publisher Harlequin UK Ltd. It was founded in 1908 by Gerald Rusgrove Mills and Charles Boon as a general publisher. The company moved towards escapist fiction for women in the 1930s. In 1971, the publisher was bought by the Canadian company Harlequin Enterprises, its North American distributor based in Toronto, with whom it had a long informal partnership. The two companies offer a number of imprints that between them account for almost three-quarters of the romance paperbacks published in Britain. Its print books are presently out-numbered and out-sold by the company's e-books, which allowed the publisher to double its output.

Lesbian pulp fiction is a genre of lesbian literature that refers to any mid-20th century paperback novel or pulp magazine with overtly lesbian themes and content. Lesbian pulp fiction was published in the 1950s and 1960s by many of the same paperback publishing houses as other genres of fiction, including westerns, romances, and detective fiction. Because very little other literature was available for and about lesbians at this time, quite often these books were the only reference the public had for modeling what lesbians were. English professor Stephanie Foote commented on the importance of lesbian pulp novels to the lesbian identity prior to the rise of organized feminism: "Pulps have been understood as signs of a secret history of readers, and they have been valued because they have been read. The more they are read, the more they are valued, and the more they are read, the closer the relationship between the very act of circulation and reading and the construction of a lesbian community becomes…. Characters use the reading of novels as a way to understand that they are not alone."

Charles Edward Mudie , English publisher and founder of Mudie's Lending Library and Mudie's Subscription Library, was the son of a second-hand bookseller and newsagent. Mudie's efficient distribution system and vast supply of texts revolutionized the circulating library movement, while his "select" library influenced Victorian middle-class values and the structure of the three-volume novel. He was also the first publisher of James Russell Lowell's poems in England, and of Emerson's Man Thinking.

Minerva Press was a publishing house, notable for creating a lucrative market in sentimental and Gothic fiction, active in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. It was established by William Lane at No 33 Leadenhall Street, London, when he moved his circulating library there in about 1790.

The three-volume novel was a standard form of publishing for British fiction during the nineteenth century. It was a significant stage in the development of the modern novel as a form of popular literature in Western culture.

A subscription library is a library that is financed by private funds either from membership fees or endowments. Unlike a public library, access is often restricted to members, but access rights can also be given to non-members, such as students.

Lesbian literature is a subgenre of literature addressing lesbian themes. It includes poetry, plays, fiction addressing lesbian characters, and non-fiction about lesbian-interest topics.

In literature, a serial is a printing or publishing format by which a single larger work, often a work of narrative fiction, is published in smaller, sequential instalments. The instalments are also known as numbers, parts, fascicules or fascicles, and may be released either as separate publications or within sequential issues of a periodical publication, such as a magazine or newspaper.

A novel is a relatively long work of narrative fiction, typically written in prose and published as a book. The present English word for a long work of prose fiction derives from the Italian: novella for "new", "news", or "short story of something new", itself from the Latin: novella, a singular noun use of the neuter plural of novellus, diminutive of novus, meaning "new". Some novelists, including Nathaniel Hawthorne, Herman Melville, Ann Radcliffe, John Cowper Powys, preferred the term "romance" to describe their novels.

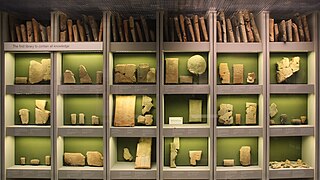

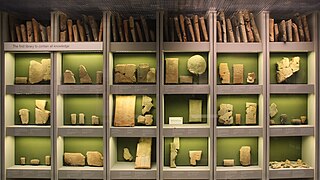

The history of libraries began with the first efforts to organize collections of documents. Topics of interest include accessibility of the collection, acquisition of materials, arrangement and finding tools, the book trade, the influence of the physical properties of the different writing materials, language distribution, role in education, rates of literacy, budgets, staffing, libraries for targeted audiences, architectural merit, patterns of usage, and the role of libraries in a nation's cultural heritage, and the role of government, church or private sponsorship. Computerization and digitization arose from the 1960s, and changed many aspects of libraries.

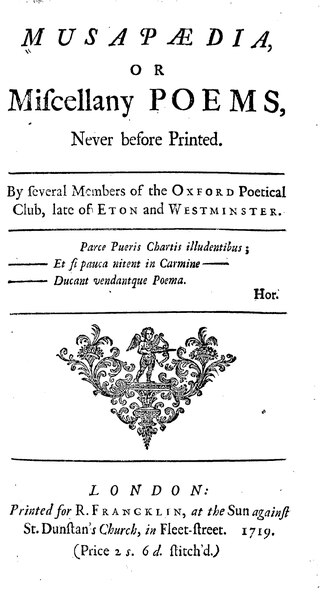

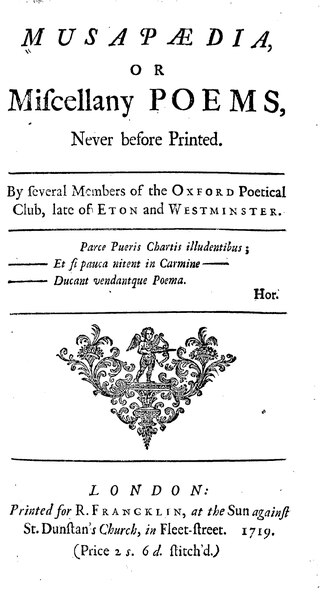

A miscellany is a collection of various pieces of writing by different authors. Meaning a mixture, medley, or assortment, a miscellany can include pieces on many subjects and in a variety of different forms. In contrast to anthologies, whose aim is to give a selective and canonical view of literature, miscellanies were produced for the entertainment of a contemporary audience and so instead emphasise collectiveness and popularity. Laura Mandell and Rita Raley state:

This last distinction is quite often visible in the basic categorical differences between anthologies on the one hand, and all other types of collections on the other, for it is in the one that we read poems of excellence, the "best of English poetry," and it is in the other that we read poems of interest. Out of the differences between a principle of selection and a principle of collection, then, comes a difference in aesthetic value, which is precisely what is at issue in the debates over the "proper" material for inclusion into the canon.

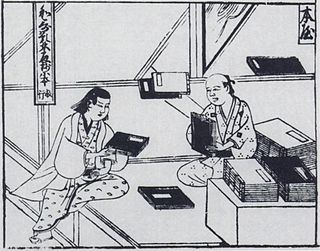

The selling of books dates back to ancient times. The founding of libraries in c.300 BC stimulated the energies of the Athenian booksellers. In Rome, toward the end of the republic, it became the fashion to have a library, and Roman booksellers carried on a flourishing trade.