The Nazi term Gleichschaltung or "coordination" was the process of Nazification by which Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party successively established a system of totalitarian control and coordination over all aspects of German society and societies occupied by Nazi Germany "from the economy and trade associations to the media, culture and education". Although the Weimar Constitution remained nominally in effect until Germany's surrender following World War II, near total Nazification had been secured by the 1935 resolutions approved during the Nuremberg Rally, when the symbols of the Nazi Party and the state were fused and German Jews were deprived of their citizenship.

The League of German Girls or the Band of German Maidens was the girls' wing of the Nazi Party youth movement, the Hitler Youth. It was the only legal female youth organization in Nazi Germany.

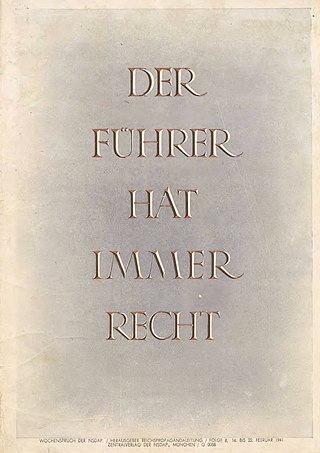

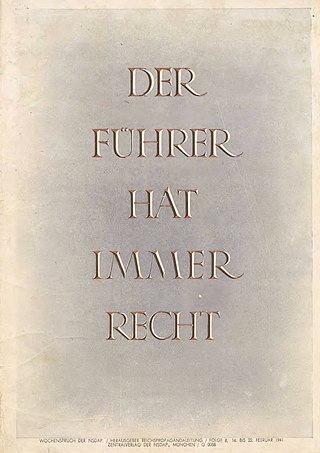

The Führerprinzip prescribed the fundamental basis of political authority in the Government of Nazi Germany. This principle can be most succinctly understood to mean that "the Führer's word is above all written law" and that governmental policies, decisions, and offices ought to work toward the realization of this end. In actual political usage, it refers mainly to the practice of dictatorship within the ranks of a political party itself, and as such, it has become an earmark of political fascism. Nazi Germany aimed to implement the leader principle at all levels of society, with as many organizations and institutions as possible being run by an individual appointed leader rather than by an elected committee. This included schools, sports associations, factories, and more. A common theme of Nazi propaganda was that of a single heroic leader overcoming the adversity of committees, bureaucrats and parliaments. German history, from Frederick the Great and Otto von Bismarck, and Nordic sagas were interpreted to emphasize the value of unquestioning obedience to a visionary leader.

Achim Gercke was a German politician.

Dr. Walter Gross was a German physician appointed to create the Office for Enlightenment on Population Policy and Racial Welfare for the Nazi Party. He headed this office, renamed the Office of Racial Policy in 1934, until his suicide at the close of World War II.

Gertrud Emma Scholtz-Klink, néeTreusch, later known as Maria Stuckebrock, was a Nazi Party member and leader of the National Socialist Women's League (NS-Frauenschaft) in Nazi Germany.

Volksgemeinschaft is a German expression meaning "people's community", "folk community", "national community", or "racial community", depending on the translation of its component term Volk. This expression originally became popular during World War I as Germans rallied in support of the war, and many experienced "relief that at one fell swoop all social and political divisions could be solved in the great national equation". The idea of a Volksgemeinschaft was rooted in the notion of uniting people across class divides to achieve a national purpose, and the hope that national unity would "obliterate all conflicts - between employers and employees, town and countryside, producers and consumers, industry and craft".

Sir Richard John Evans is a British historian of 19th- and 20th-century Europe with a focus on Germany. He is the author of eighteen books, including his three-volume The Third Reich Trilogy (2003–2008). Evans was Regius Professor of History at the University of Cambridge from 2008 until his retirement in 2014, and President of Cambridge's Wolfson College from 2010 to 2017. He has been Provost of Gresham College in London since 2014. Evans was appointed Knight Bachelor for services to scholarship in the 2012 Birthday Honours.

Das Schwarze Korps was the official newspaper of the Schutzstaffel (SS). This newspaper was published on Wednesdays and distributed free of charge. All SS members were encouraged to read it. The chief editor was SS leader Gunter d'Alquen; the publisher was Max Amann of the Franz-Eher-Verlag publishing company. The paper was hostile to many groups, with frequent articles condemning the Catholic Church, Jews, Communism, Freemasonry, and others.

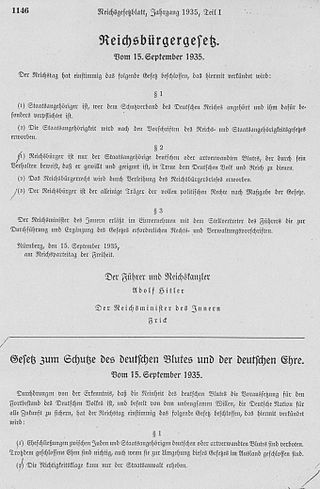

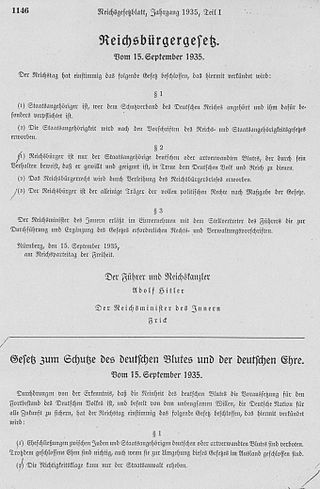

Rassenschande or Blutschande was an anti-miscegenation concept in Nazi German racial policy, pertaining to sexual relations between Aryans and non-Aryans. It was put into practice by policies like the Aryan certificate requirement, and later by anti-miscegenation laws such as the Nuremberg Laws, adopted unanimously by the Reichstag on 15 September 1935. Initially, these laws referred predominantly to relations between ethnic Germans and non-Aryans, regardless of citizenship. In the early stages the culprits were targeted informally; later, they were punished systematically and legally.

Franz Gürtner was a German Minister of Justice in the governments of Franz von Papen, Kurt von Schleicher and Adolf Hitler. Gürtner was responsible for coordinating jurisprudence in Nazi Germany and provided official sanction and legal grounds for a series of repressive actions under the Nazi regime from 1933 until his death in 1941.

The propaganda used by the German Nazi Party in the years leading up to and during Adolf Hitler's dictatorship of Germany from 1933 to 1945 was a crucial instrument for acquiring and maintaining power, and for the implementation of Nazi policies.

Georg Paul Erich Hilgenfeldt was a high Nazi Party government official.

Protofeminism is a concept that anticipates modern feminism in eras when the feminist concept as such was still unknown. This refers particularly to times before the 20th century, although the precise usage is disputed, as 18th-century feminism and 19th-century feminism are often subsumed into "feminism". The usefulness of the term protofeminist has been questioned by some modern scholars, as has the term postfeminist.

The propaganda of the Nazi regime that governed Germany from 1933 to 1945 promoted Nazi ideology by demonizing the enemies of the Nazi Party, notably Jews and communists, but also capitalists and intellectuals. It promoted the values asserted by the Nazis, including heroic death, Führerprinzip, Volksgemeinschaft, Blut und Boden and pride in the Germanic Herrenvolk. Propaganda was also used to maintain the cult of personality around Nazi leader Adolf Hitler, and to promote campaigns for eugenics and the annexation of German-speaking areas. After the outbreak of World War II, Nazi propaganda vilified Germany's enemies, notably the United Kingdom, the Soviet Union and the United States, and in 1943 exhorted the population to total war.

Women in Nazi Germany were subject to doctrines of Nazism by the Nazi Party (NSDAP), which promoted exclusion of women from the political and academic life of Germany as well as its executive body and executive committees. On the other hand, whether through sheer numbers, lack of local organization, or both, many German women did indeed become Nazi Party members. In spite of this, the Nazi regime officially encouraged and pressured women to fill the roles of mother and wife only. Women were excluded from all other positions of responsibility, including political and academic spheres.

Feminism in Germany as a modern movement began during the Wilhelmine period (1888–1918) with individual women and women's rights groups pressuring a range of traditional institutions, from universities to government, to open their doors to women. This movement culminated in women's suffrage in 1919. Later waves of feminist activists pushed to expand women's rights.

The history of German women covers gender roles, personalities and movements from medieval times to the present in German-speaking lands.

The Crucifix Decrees were part of the Nazi Regime's efforts to secularize public life. For example, crucifixes throughout public places like schools were to be replaced with the Führer's picture. The Crucifix Decrees throughout the years of 1935 to 1941 sparked protests against removing crucifixes from traditional places. Protests notably occurred in Oldenburg in 1936, Frankenholz (Saarland) and Frauenberg in 1937, and in Bavaria in 1941. These incidents prompted Nazi party leaders to back away from crucifix removals in 1941.

On 30 January 1939, Nazi German dictator Adolf Hitler gave a speech in the Kroll Opera House to the Reichstag delegates, which is best known for the prediction he made that "the annihilation of the Jewish race in Europe" would ensue if another world war were to occur.